What seemed like a certainty in the wee hours of the morning on Friday, June 9, now seems far more treacherous nearly a week later.![]()

![]()

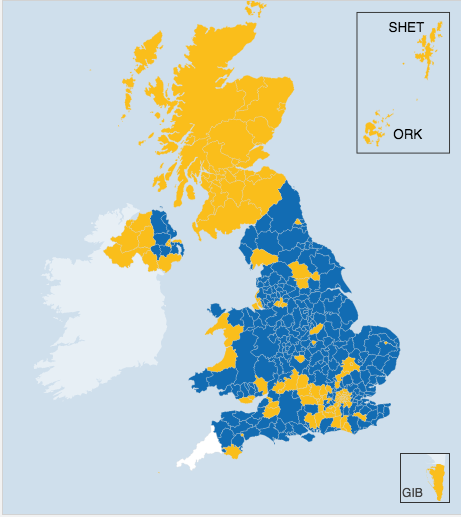

British prime minister Theresa May may have assured nervous Conservative MPs Monday that she can steady a minority government. With contrition for her campaign missteps and the loss of 13 seats (and the Tory majority that David Cameron won just two years ago) and claiming, ‘I got us into this mess, and I will get us out,’ May seems to have united her parliamentary caucus, at least temporarily, behind her leadership.

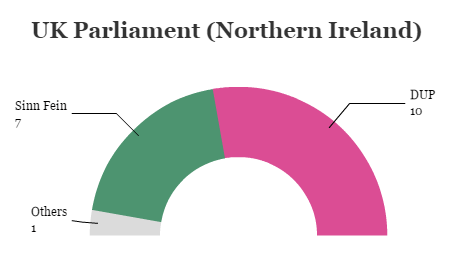

But it may be even more difficult than May might have realized to secure and maintain a ‘confidence and supply’ arrangement with Northern Ireland’s socially conservative Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). Though a formal coalition was always unlikely, May will need the DUP’s 10 MPs to have any hope of a reliable majority in the House of Commons.

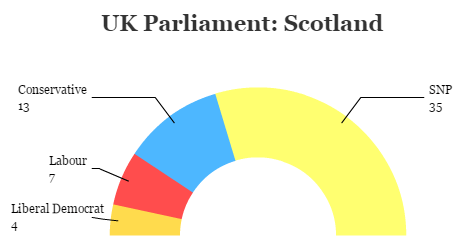

The deeply evangelical DUP’s hard-line stand on abortion, women’s rights and LGBT rights (its founder, Ian Paisley, once led a famous ‘Save Ulster from Sodomy’ campaign) have alarmed many, including some leading Tories, such as the Scottish Conservative Party’s openly gay leader Ruth Davidson, whose newly elected bloc of 13 MPs may function as a liberal (and relatively pro-European) Tory bulwark in the new parliament.

Notably, in Northern Ireland, reflecting trends that began in the early 2000s and have only accelerated since, the DUP and the republican Sinn Féin each won record numbers of seats. Ironically, that benefits May in two ways. First, it gives her more DUP MPs to shore up a Tory-led majority; second, it means a smaller number to reach an absolute majority in the House of Commons. That’s because Sinn Féin, which advocates Northern Ireland’s ultimate unification with the rest of Ireland, refuses to swear an oath to a British monarch and, correspondingly, refuses to take its seats at Westminster. With those seven Sinn Féin MPs abstaining, it means May needs three less MPs in total for a majority.

Forebodingly, former prime minister John Major on Tuesday warned May against working with the DUP, even as May was engaged in negotiations the same day with DUP leader Arlene Foster and deputy DUP leader Nigel Dodds to foster an agreement. (The pending Tory-DUP deal was, according to reports, set to go ahead on Wednesday, but has been postponed until next week in light of the deadly blaze at Grenfell Towers). Major joins a growing chorus of leading figures urging caution, including Jonathan Powell, the Labour chief of staff who helped negotiate with Northern Ireland between 1997 and 2007, and Leo Varadkar, the newly elected Fine Gael leader who became Ireland’s taoiseach on Wednesday.

Forebodingly, former prime minister John Major on Tuesday warned May against working with the DUP, even as May was engaged in negotiations the same day with DUP leader Arlene Foster and deputy DUP leader Nigel Dodds to foster an agreement. (The pending Tory-DUP deal was, according to reports, set to go ahead on Wednesday, but has been postponed until next week in light of the deadly blaze at Grenfell Towers). Major joins a growing chorus of leading figures urging caution, including Jonathan Powell, the Labour chief of staff who helped negotiate with Northern Ireland between 1997 and 2007, and Leo Varadkar, the newly elected Fine Gael leader who became Ireland’s taoiseach on Wednesday.

Why everyone from Major to Labour is so wary of the DUP

Major’s wariness comes, in part, from his own history.

After Major won an unexpected victory in the 1992 general election against Neil Kinnock’s Labour, the Conservatives lost their majority in December 1996 due to by-election losses and attrition, and Major turned to the then-dominant force in Northern Ireland’s unionist and Protestant politics, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP). That arrangement lasted barely six months, coming right before the ‘New Labour’ landslide that swept Tony Blair into power in May 2017.

The UUP was, at the time, engaged in the negotiations that would two years later blossom into the ‘Good Friday’ Agreement. The UUP leader, David Trimble, shared the 1998 Nobel Peace Prize with his counterpart John Hume, the leader of the republican (and largely Catholic) Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP).

While Major’s government leaned on the Ulster Unionists, the DUP in the 1990s was a far more right-wing and recalcitrant group. Indeed, the Tories have never formally turned to the DUP for support like May is now doing.

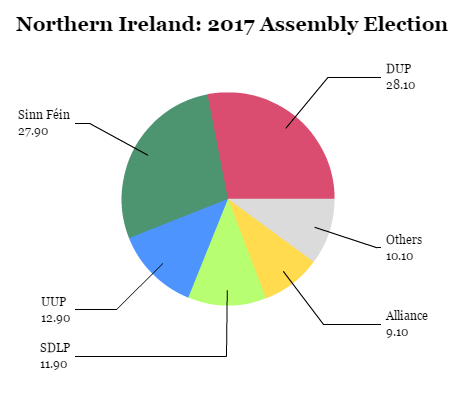

Founded in 1971 by Paisley, a Presbyterian fundamentalist preacher, the DUP bitterly opposed the Good Friday Agreement on the grounds that it allowed the republican Sinn Féin, a party with ties to the Irish Republican Army, to hold public office. By the early 2000s, moreover, the DUP had eclipsed the UUP as the leading unionist party in Northern Ireland, while Sinn Féin was itself eclipsing the SDLP as the leading party of the Catholic, republican left. Those tectonic changes in Northern Irish politics brought a halt, after just four years, to the widely hailed devolution in Northern Ireland, collapsing a power-sharing arrangement between the UUP and the SDLP.

Between 2002 and 2007, as internal unionist and republican politics were sorting in new directions, Northern Ireland reverted to a period of home rule through the Northern Ireland office. Eventually, the DUP and Sinn Féin agreed to a new power-sharing agreement of their own, a step that more firmly enshrined the Good Friday framework under Sinn Féin’s Martin McGuinness, on the one hand, and under the DUP, first under Paisley, then under his successor Peter Robinson and from January 2016 until January 2017, Foster.

McGuinness earlier this year bowed out of the power-sharing agreement over the botched Renewable Heat Initiative, a scheme hatched by Foster when she was Northern Irish minister for enterprise. The idea was to offer subsidies to businesses to use wood pellets and other renewable heat sources. But businesses instead abused those subsidies so corruptly that they ultimately received more subsidies than the total amount spent on wood pellets altogether, costing the Northern Irish government nearly £500 million.

A snap election in March did little to solve the impasse; Sinn Féin and the DUP essentially tied, and Sinn Féin came incredibly close to emerging as the leading party for the first time in Northern Irish history, as unionist parties lost their majority for the first time as well. McGuinness himself died days after the regional elections. When May called a snap election nationally, James Brokenshire, the secretary of state for Northern Ireland, prolonged the deadline to reach a deal until June 29, well after the general election result.

Under the Good Friday framework, the national government has an obligation of neutrality in helping various parties reach a power-sharing arrangement in the Stormont-based Northern Irish Assembly. Major and others worry that with the new Conservative government so dependent on DUP votes for its survival, that neutrality will be threatened. That’s doubly dangerous, first because it comes at a time when the power-sharing arrangement between the DUP and Sinn Féin is in danger of collapse after a decade and, secondly, because both unionists and republicans worry about the consequences of Brexit, with fears that the re-imposition of a genuine border could re-ignite tensions after EU guarantees and the Good Friday Agreement virtually erased it 20 years ago.

Moreover, a Tory-DUP deal might buy May just months, not years. In 2016, deaths, resignations and other matters resulted in seven by-elections for parliamentary seats. With the Tories now polling behind Labour in the wake of last week’s election, the DUP’s negotiating position would strengthen with every Conservative by-election loss, and a handful of by-election losses would render the Tory minority unsalvageable, even with DUP support.

So these are all legitimate concerns, of course, and it’s why May is wisely inviting leaders from all five major parties to discuss power-sharing in Northern Ireland, including Sinn Féin, on Thursday.

Reason to be optimistic about a Tory-DUP alliance?

While the stakes of a significant DUP role at Westminster are high, there’s nevertheless a strong chance that the DUP’s influence could ultimately benefit Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom more generally.

After all, if the late Martin McGuinness, a militant republican, could make a deal with the DUP, certainly Theresa May can too.

Deal or no deal, though, Sinn Féin seems unlikely to continue its power-sharing arrangement with the DUP so long as Brexit negotiations are ongoing, because signing off on a hard Brexit (or even a soft Brexit) would be so politically toxic for Sinn Féin. The DUP is the only party that supported Brexit last year, even though Northern Ireland backed ‘Remain’ by a margin of 56% to 44%. Sinn Féin’s voters overwhelmingly backed Remain, and they especially loathe the idea of re-introducing a border with the Republic of Ireland (which of course remains a full member of the European Union). Despite the incompetence of the ‘Cash for Ash’ scandal, it was always more a fig leaf for Sinn Féin than a genuine grievance.

Today, it feels like a near-certainly that home rule will become reality on June 29, and Brokenshire, the Conservative secretary of state for Northern Ireland, was always going to have greater unionist sympathies. That was true even when polls showed the Tories winning a 100-plus majority back in April.

Entering a period of home rule, Sinn Féin hopes (with some reason) to consolidate its growing position as the part of the Catholic republican left. Meanwhile, if it concludes a deal with May, the DUP likewise hopes to consolidate its own support by bringing more economic aid to Northern Ireland as its price for floating May’s government. It’s a win-win situation for both parties, who see it as an opportunity for dual, perhaps fatal, blows to the UUP and the SDLP (and maybe the non-sectarian Alliance as well), all of which lost their remaining Westminster seats last Thursday.

It’s true that the DUP has an incredibly conservative position on social issues like gay rights, abortion and same-sex marriage. Northern Ireland is the only part of the United Kingdom where marriage equality isn’t the law of the land. But as even leading LGBT activists in Northern Ireland admit, the DUP’s stand today is far weaker than the Paisley view of the 1970s. Moreover, though it was Cameron who shepherded same-sex marriage though parliament in 2013, more Tories opposed it (134), including then-home secretary May, than supported it (126). So it’s not just the DUP that has had a tough time accepting LGBT rights and marriage equality.

Moreover, as the DUP and Sinn Féin have become the leading parties for their respective unionist and republican electorates, they’ve shed some of the harder edges of their pasts. The DUP is simply not the same today under Foster, who is Anglican (not Presbyterian) and who was originally elected as a member of the Northern Irish Assembly from the UUP before switching to the DUP in 2004, as it was under Paisley. Dodds, who has served as deputy leader since 2008, is a Cambridge-educated pragmatist and dealmaker.

The same is true for Sinn Féin, whose leader in Northern Ireland is Michelle O’Neill, a run-of-the-mill social democrat who was a child and teenager during the Troubles, and accordingly far less tainted by the legacy of the IRA violence of the 1970s and 1980s (unlike McGuinness and Gerry Adams).

To that end, the DUP is also reportedly rebuffing the Orange Order and hard-line Presbyterian demands to re-open a once-settled issue involving Ulster unionist parade routes designed to provoke Northern Irish republicans. That’s a responsible step, as DUP leaders have made clear their demands from May will be non-sectarian in nature. Though, as Major cautions, English and Scottish voters may well be annoyed at more funds going to Northern Ireland, even Sinn Féin, I suspect, will be happy to see more money from London, given that Brexit means financial support from Brussels will chiefly come to an end (unless funneled through Ireland, whose government, by the way, would balk at picking up the hefty tab that London currently pays, in the unlikely event of unification).

Though the DUP is pro-Brexit, it is in favor of a relatively softer Brexit that keeps Northern Ireland within the EU single market, and it also opposes restoring a hard border with the Republic of Ireland. Given that the border issue is the most delicate and perhaps most intractable surrounding the Article 50 negotiations, the DUP’s input may be helpful. Though DUP officials are reportedly asking May for a pledge not to call a ‘border poll’ over the term of the next government, it’s not clear there’s anything like the sufficiently widespread support today (or in the foreseeable future) for Irish unification to justify May calling such a referendum under the Good Friday framework anyway — though it’s a matter that could arise following a hard Brexit. In the long run, a softer Brexit is far more important to stability and peace in Northern Ireland than any short-term turmoil related to the DUP’s role at Westminster. If both May and Foster exercise caution and restraint, the DUP could help nudge a better outcome for all of Northern Ireland.