Flushing, in Queens, is one of the most Asian neighborhoods in the United States.

Flushing, in Queens, is one of the most Asian neighborhoods in the United States.

Apparently, the swing among Asian Americans between the 2012 general election in the United States and the 2014 midterm elections was a staggering 46%:![]()

![]()

Note the big swing in the Asian voting bloc, too. In 2012, strong support for the president among Asian-American voters was a surprise. Asian voters preferred the president by 47 points. In 2014, the (low turnout) group split about evenly. It was a 46-point swing.

That still translates to a fairly robust tilt among Asian Americans toward Democrats — just not the overwhelming trend that we saw in 2012 and 2008 and, even to some degree, 2010. Other exit polling shows that Asian Americans still strongly supported Democrats — in Virginia, they favored incumbent Democratic senator Mark Warner over Republican challenger Ed Gillespie by a margin of 68% to 29%, for example.

But why should Asian Americans necessarily lean to the left? The Asian American experience in the United States is extremely varied, and it’s a growing bloc of disparate cultures and experiences. In that regard, Asian Americans are just like Latin Americans, who come from an equally broad range of national and ethnic background. Mexican Americans in California may have different political views that Mexican Americans in Texas, to say nothing of Salvadorans in Maryland, Cubans in New Jersey or Dominicans in Florida.

The same goes for Asian Americans.

So what are we talking about when we say, ‘Asian Americans?’

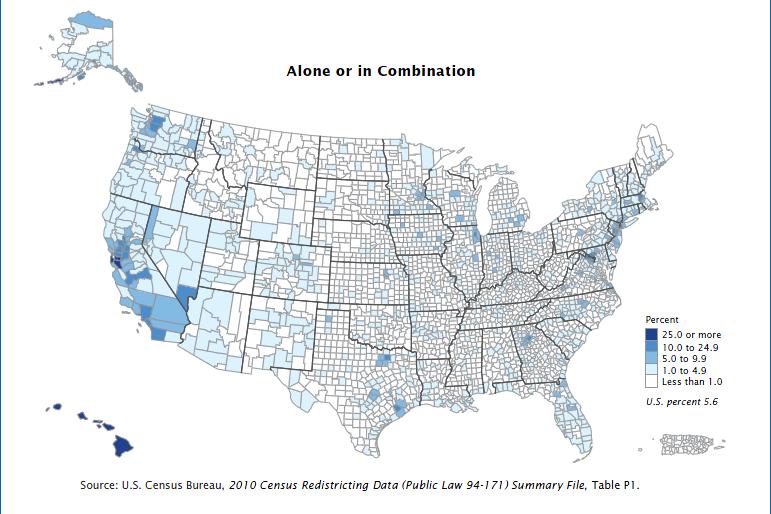

As Taeku Lee notes in a great pre-election summary for the Brookings Institution, Asian Americans comprise nearly 6% of the US population (around 20 million and rising) and around 3% of the electorate, though it’s a much larger proportion in California (around 14.9% of the state population), New York (8.2%) and other states, including Washington, Nevada and New Jersey each around 9%). Hawaii, which is itself part of northern Polynesia, is the only Asian-majority state (57.4%).

Among those 20 million or so Asian Americans, three-fourths of them were born outside the United States, and two-thirds gained their citizenship through nationalization. Since the Great Recession slowed migration from Mexico and Central America to a slow crawl, Asia (and not Latin America) is the largest source of migration to the United States:

Though small, these numbers are not negligible. For one thing, no other racial/ethnic segment of the U.S. population has been growing faster than Asian Americans. Between the 2000 and 2010 decennial censuses, the U.S. Asian population grew 46 percent; Latino population growth came in a close second at 43 percent. In fact, Asia is now the largest source of population growth through in-migration to the U.S.: since 2008, Asia has accounted for more than 40 percent of new immigrants to the U.S.; by comparison slightly over 31 percent during this period have come from Mexico, Central America, and South America. These growth rates are reflected in voter turnout: as recently as 1996, Asians were only 1.6 percent of votes counted; that proportion nearly doubled by 2012. As of 2012, Asian Americans were more than 10 percent of the citizen voting-age population in two states, 33 counties, and 45 Congressional districts. And growth is expected to continue into the foreseeable future: by 2050, the U.S. Asian population is forecast to nearly double to close to 36 million in number.

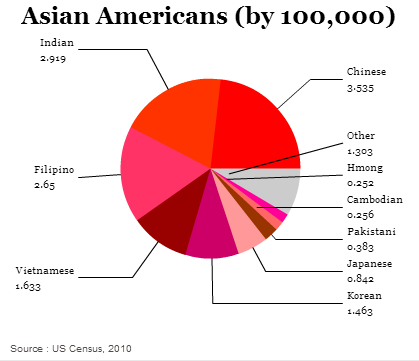

The two largest groups within the penumbra of ‘Asian American’ are Chinese American and Indian American, though they hardly monopolize the category:

As a group, on average, they have higher incomes and higher educational achievement than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States, though Asian Americans remain underrepresented within the US national electorate.

It’s worth noting that both China and India have populations of over 1 billion people each, with dozens of languages and regional cultures, so the fragmentation of the Asian American population is even more diverse than national breakdown.

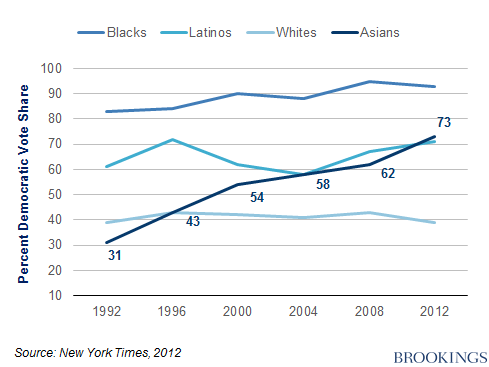

Though exit polls showed that fully 73% of Asian Americans supported Obama’s reelection in 2012, that was even higher than the 62% Democratic vote in 2008, and much higher than the 31% that supported then-Arkansas governor Bill Clinton in 1992 and the 54% that supported Democratic vice president Al Gore.

That marks, as Lee explains, a huge shift among Asian American support in two decades:

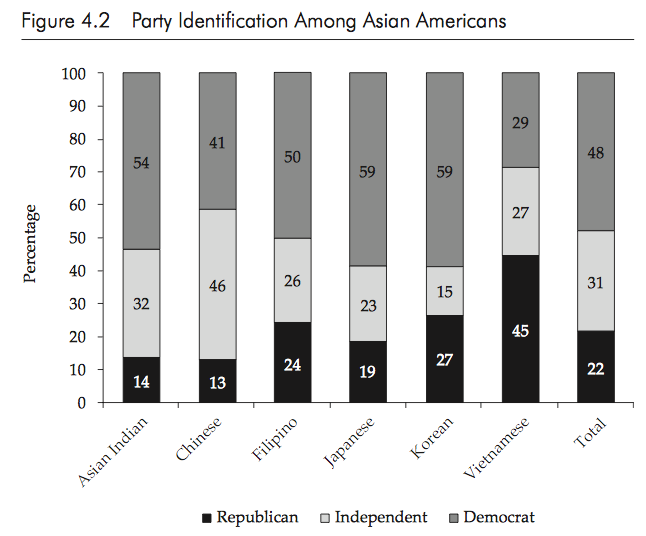

But it’s vital to remember that ‘Asian Americans’ aren’t a single bloc, and they vary significantly from subgroup to subgroup in their political leanings, making them an increasingly crucial swing group, in both state and national elections, according to this 2008 survey, which comes from this 2011 Asian American Political Participation report from the Russell Sage Foundation:

According to this survey, Indian American and Chinese American voters (the two largest national blocs of Asian Americans) are least likely to vote Republican, but are most likely to call themselves ‘independent.’

Meanwhile Vietnamese Americans, by far, support Republicans in greater proportion, while Japanese Americans, Korean Americans and Filipino Americans are most likely to support Democrats.

Asians come to the United States from a vastly different set of political and governance structures. India and the Philippines have had a long-functioning, if chaotic and corrupt, democratic system. Pakistan’s government has been a mix of democratic, civilian leadership interspersed with military coups. Japan and South Korea, since the 1980s at least, each have a relatively collaborative system of democracy and the most fully developed regulatory states in east Asia. The People’s Republic of China and Vietnam are, at least in name, still communist states with no democracy and sharp limits on individual freedom.

Even among the more democratic states in Asia, populations vary widely. Indians this spring elected Narendra Modi, the leader of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP

Similarly, it’s hard to find any analogue for the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō), which essentially dominates Japan’s government. The greater competition for real power in Japan is within the various factions of the LDP, not between the LDP and opposition parties.

Region also plays a role. Chuncheon and Jeolla, in the far southwest of South Korea, are much more to the left than the rest of the country. Though Bangkok and the south of Thailand have long been more conservative and supportive of business-friendly candidates, northern Thailand and northeastern Issan are much poorer and more fertile ground for interventionist and populist politics. Immigrants from Cantonese-speaking Chinese from Guangdong and the hinterland of Hong Kong have had much more exposure to market economies than Mandarin-speakers in the north.

That explains why both Republicans and Democrats have raised the profiles of prominent Asian American officials over the past two decades. The gradual rise in participation and importance of the Asian American vote also coincides with the growth of many figures on both sides of the political spectrum in the United States:

- Gary Locke, a third-generation Chinese American, was first elected to two terms as governor of Washington state in 1997, was the first Chinese American to serve as governor in the United States, and he subsequently served as Obama’s commerce secretary and most recently as US ambassador to China.

- Bobby Jindal, the son of Punjabi immigrants, became the first Indian American governor when he was elected as Louisiana’s governor in 2007.

- Nikki Haley, the daughter of immigrants from Amritsar (also in the Indian state of Punjab), another Indian American, became the first Sikh American governor with her election in 2010 in South Carolina.

- Norman Mineta, a longtime member of the House of Representatives representing Silicon Valley, became the first Asian American cabinet member in 2000 with his appointment as Clinton’s commerce secretary, and he remained in the Cabinet as secretary of transportation from 2001 to 2006 under Republican George W. Bush. Mineta is the son of Japanese American parents who were prohibited from citizenship due to the Asian Exclusion Act and Mineta, as a child, was interred during World War II when the United States was at war with Japan.

- Taipei-born Elaine Chao, the wife of incoming Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, who won reelection in Kentucky on Tuesday, served as the Bush administration’s labor secretary.

- Steven Chu, a Chinese American physicist, served as Obama’s first-term energy secretary.

- The Seoul-born physician Jim Yong Kim, the former president of Dartmouth College, has since 2012 served as president of the World Bank, a position traditionally held by an American official.

- Neel Kashkari, the son of Kashmiri immigrants, waged an uphill (and unsuccessful) challenge in Tuesday’s California gubernatorial election against Democratic incumbent Jerry Brown, and previously oversaw the US treasury department’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) in the final months of the Bush administration.

Before the election, however, Politico argued that there are some common underlying political values among most Asian American groups:

Partisan strategists and Asian-American activists say that even across culturally disparate immigrant groups, there are common preoccupations – an intense focus on education, for instance, and concern about the economic environment for small, family-owned businesses. Increasingly, there is also a broad affinity for the Democratic Party – seen overwhelmingly as the party that stands for racial and ethnic diversity, and a more inclusive federal immigration policy.

But just as Bush in the 2000s made a strong push for Latino voters, with some success, one of the most important lessons of the 2014 midterms is that the growing Asian American bloc could also emerge as a swing vote across the United States in 2016 and beyond.