Today is a landmark for the rise and acceptance of openly LGBT elected officials, as the 38-year-old Leo Varadkar, minister of social protection, easily won the leadership of Ireland’s governing Fine Gael, defeating Simon Coveney, housing minister.![]()

Varadkar will almost certainly become Ireland’s next Taoiseach — essentially, Ireland’s prime minister — next week. That will make him Ireland’s first openly gay leader, and as the son of an Indian immigrant (who, like his son, is a doctor by training), it will make him a Taoiseach with roots both inside Ireland and far outside its borders.

Varadkar will hardly have a honeymoon, however.

Partially, that’s because he was elected leader solely on the basis of his support among elected Fine Gael officials (members of parliament, senators and the like) and among local Fine Gael councillors. Together, those figures’ support account for 75% of the leadership in the party’s lopsided electoral college system that allocates most of the leadership decision-making to fellow officeholders.

* * * * *

RELATED: In Varadkar, Ireland may be

about to have its first openly gay leader

* * * * *

The other 25% in the Fine Gael electoral college reflects the support of rank-and-file party members and, among them, Coveney won around 65% of the membership, defeating Varadkar by a nearly two-to-one margin. If Fine Gael chose its leader like either the Conservatives or Labour in the United Kingdom, Coveney would have easily won. American readers should think of it this way — imagine the Democratic Party presidential nomination was determined 75% by superdelegates; that’s essentially how Ireland’s governing party chose its leader today.

Obviously, in a democracy like Ireland, that leaves Varadkar in an awkward position because he doesn’t command popular support even within his own party. While Coveney was expected to do better among party members than among party officials, Varadkar wasn’t expected to fare so poorly among everyday voters. That could severely weaken Varadkar’s mandate as Taoiseach, and it’s yet another sign that Ireland will go to the polls far sooner than the next scheduled election in 2021 — and that Varadkar may struggle to win a third term for Fine Gael, which now governs as a minority government after losing seats in the 2016 general election.

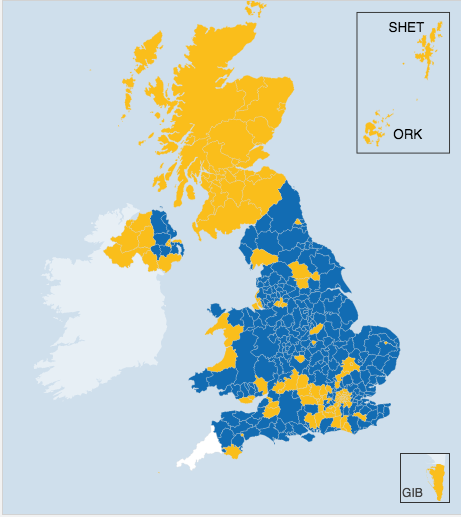

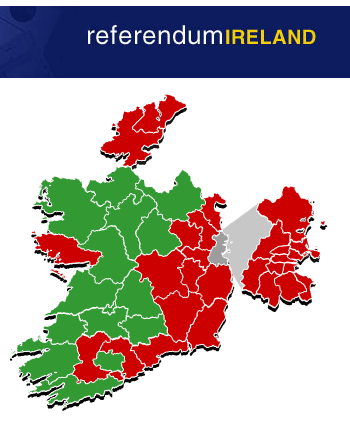

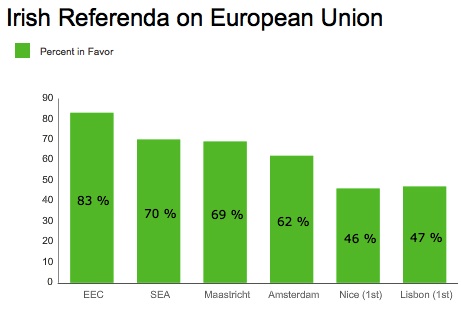

It’s still a wonderful milestone for Irish and European democracy that both an openly gay man and the son of an Indian immigrant will become Ireland’s head of government next week. It sets an example that gives hope to two groups that have been traditionally marginalized. With the 2015 referendum that overwhelmingly endorsed same-sex marriage, and with Ireland’s relatively welcoming embrace of immigrants from within the European Union and beyond, that may not matter so much in Ireland. But it’s a powerful symbol that will reverberate throughout European politics, no more so, perhaps, than in Northern Ireland, the only part of the United Kingdom where same-sex marriage is still banned, and where a majority of Protestant unionists voted for Brexit last June.

Within Europe, Varadkar will be only the fourth openly gay leader after Luxembourg’s prime minister Xavier Bettel, former Belgian prime minister Elio Di Rupo and former Icelandic prime minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir.

All of those officials, however, come from the political left and center-left, unlike Varadkar, who very much has Tory sensibilities and comes from the economic right wing of his party. From an international perspective, classical liberals and those on the right and center-right will cheer Varadkar’s rise, which shows you don’t have to be leftist to be gay and successful in politics. Progressives (especially those in the United States) will find little else to recommend Varadkar, who wants to cut taxes, cut spending and, earlier in the campaign, proclaimed himself the candidate for ‘people who get up early in the morning.’

But in domestic politics, the real winner from the Fine Gael leadership today might have been Micheál Martin, the leader of Fianna Fáil, Ireland’s more socially conservative right-wing party (as opposed to Fine Gael’s more socially liberal center-right orientation). Traditionally, the two parties have been fierce rivals, dating back to the days of the Irish civil war in the 1920s and its aftermath.

Under outgoing Taoiseach Enda Kenny, Fine Gael swept to power in 2011, largely because Irish voters were angry at the sharp recession that followed on Fianna Fáil’s watch, as the ‘Celtic Tiger’ gains of the late 1990s and early 2000s seemed to evaporate overnight. Much of Kenny’s premiership has focused on bringing Ireland out of its bailout program and then back to impressive economic growth (over 5% GNP growth, for example, in 2015 and in 2016). But Kenny stepped down earlier this year, in large part due to a widespread corruption scandal revealed years ago within the national police force.

Though Fine Gael won the largest number of seats to the Dáil (the lower house of the Irish parliament) in the 2016 election, Kenny’s party lost seven seats in the 158-member Dáil, and its preferred coalition partner, the progressive Labour Party, was nearly wiped out. Fine Gael now holds just 50 seats in the Dáil (with the support of seven independents that join the party in government), and it governs only with the support of a handful of independents and a ‘support and confidence’ agreement with Fianna Fáil. Varadakar’s official appointment as the 14th Taoiseach will, therefore, also require Fianna Fáil’s blessing.

While the two parties are currently tied in the polls — the two parties routinely trade places for first and second place, with the republican and left-wing Sinn Féin firmly in third place — Martin can now force a snap election by revoking his party’s support for the Fine Gael minority government. That, too, puts Varadkar in a precarious position.

Labour is still stuck in mid-single-digit support as Sinn Féin consolidates support on the Irish left, while Fianna Fáil will appeal to traditional conservatives who will look to a form of Irish conservatism steeped more in social protection than in laissez-faire economics. If Varadkar tries to pursue some of his more Thatcherite policies — making it more difficult for public-sector workers to strike, for example, or passing deeper tax cuts at the expense of social services — many of Fine Gael’s supporters might easily shift to Fianna Fáil. Varadkar feels like the kind of leader who will sell very well in Dublin, but who will also flop outside Dublin — even in Fine Gael’s traditional strongholds like county Mayo in the northwest (and not because of his Indian descent or because of his sexuality).

That Varadkar lost so many of his own party’s members will only encourage Martin and Fianna Fáil.