In the United States, ‘Benghazi’ has become a code word for conservative Republicans hinting at a dark cover-up within the administration of US president Barack Obama about who actually perpetrated the attack on September 11, 2012 against the US consulate in Benghazi, Libya’s second-most populous city.

The furor stems largely from comments by Susan Rice, then the US ambassador to the United Nations and a candidate to succeed Hillary Clinton as US secretary of state, that indicated the attack was entirely spontaneous, caused by protests to a purported film trailer, ‘Innocence of Muslims,’ that ridiculed Islam and the prophet Mohammed. Republicans immediately seized on the comments, arguing that al-Qaeda was responsible for the attack, which left four US officials dead, including Christopher Stevens, the US ambassador to Libya at the time, a volatile period following the US-backed NATO efforts to assist rebels in their effort to end the 42-year rule of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

An amazingly detailed report in The New York Times by David Kirkpatrick on Saturday reveals that there’s no evidence that al-Qaeda was responsible for the attack. While it was more planned than the spontaneous anti-film riots that rocked the US embassy in Cairo the same day, the Benghazi incident was carried out by local extremist militias. Kirkpatrick singles out, in particular, Abu Khattala, a local construction worker and militia leader, but he also identifies other radical militias within Benghazi, such as Ansar al-Sharia, which may not have been responsible, but still seem relatively sympathetic to anti-American sentiment:

Mohammed Ali al-Zahawi, the leader of Ansar al-Shariah, told The Washington Post that he disapproved of attacking Western diplomats, but he added, “If it had been our attack on the U.S. Consulate, we would have flattened it.”

Similarly named groups have emerged throughout north Africa and the Arabian peninsula over the past few years — a group calling itself Ansar al-Sharia, not ‘al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’ (AQAP), took control of portions of southern Yemen after the battle of Zinjibar in 2011. The United States ultimately listed ‘Ansar al-Sharia’ as an alias for AQAP, but it’s unclear the degree to which the two are (or were) separate. It also underscores the degree to which local Islamist groups like AQAP are necessarily fueled by local interests and concerns . Most Yemenis fighting alongside AQAP are doing so for local reasons in a country that remains split on tribal and geographic lines — South Yemen could claim to be an independent state as recently as 1990. Groups also named Ansar al-Sharia also operate in Mali, Tunisia, Mauritania, Morocco and Egypt, and some of them have links to al-Qaeda affiliates and personnel. Others do not.

If Khattala, as The New York Times reports, is the culprit behind the consulate attack (and the US government continues to seek him in response to the attack), he fits the profile less of a notorious international terror mastermind and more of a local, off-kilter eccentric:

Sheikh Mohamed Abu Sidra, a member of Parliament from Benghazi close to many hard-line Islamists, who spent 22 years in Abu Salim, said, “Even in prison, he was always alone.” He added: “He is sincere, but he is very ignorant, and I don’t think he is 100 percent mentally fit. I always ask myself, how did he become a leader?”

Moreover, if there’s a scandal involving the Obama administration, it’s the way in which the United States came to enter the Libyan conflict in 2011. The Obama administration refused to seek authorization from the US Congress when it ordered military action in Libya in support of the NATO mission and to establish a no-fly zone, pushing a potentially unconstitutional interpretation of the 1973 War Powers Resolution, which requires Congressional authorization for open-ended conflicts that last for more than 60 days. Ironically, Obama’s case for ignoring Congress was actually stronger with respect to potential airstrikes on Syria earlier this year, though Obama’ ultimately decided to seek Congressional support for a potential military strike in August in response to the use of chemical weapons by Syria’s military.

Republicans, who control the US House of Representatives but not the US Senate, the upper house of the US Congress, just as they did in 2011, could have (and should have) held Obama more accountable for his decision vis-à-vis the War Powers Resolution. Instead, they’ve colluded with a conservative echo chamber that mutters ‘Benghazi’ like some unhinged conspiracy theory, suggesting that somehow the Obama administration purposefully lied about what happened that day. The reality is that the Obama administration was as caught off guard as anyone by the attack. Democrats that would have howled with disgust over Benghazi if it had happened under the previous administration of Republican George W. Bush have remained incredibly docile during the Obama administration — to say nothing of the Obama administration’s encroaching internet surveillance, ongoing war in Afghanistan, frequent use of drone attacks and pioneering use of ‘targeted killings’ (including assassination of US citizens).

Kirkpatrick’s report showed that while US intelligence agencies were tracing an individual with tangential ties to al-Qaeda and Osama Bin Laden, they largely missed the more local threats like Khattala and Ansar al-Sharia:

The C.I.A. kept its closest watch on people who had known ties to terrorist networks abroad, especially those connected to Al Qaeda. Intelligence briefings for diplomats often mentioned Sufian bin Qumu, a former driver for a company run by Bin Laden. Mr. Qumu had been apprehended in Pakistan in 2001 and detained for six years at Guantánamo Bay before returning home to Derna, a coastal city near Benghazi that was known for a high concentration of Islamist extremists.

But neither Mr. Qumu nor anyone else in Derna appears to have played a significant role in the attack on the American Mission, officials briefed on the investigation and the intelligence said. “We heard a lot about Sufian bin Qumu,” said one American diplomat in Libya at the time. “I don’t know if we ever heard anything about Ansar al-Shariah.”

That, in turn, highlights the real lesson of Benghazi — both the Obama administration and the national security apparatus that it has empowered, and the conservative opposition to the Obama administration are missing the larger problem with the way that the United States engages the world. It’s a point that rings most clearly in the words of Khattala himself:

“The enmity between the American government and the peoples of the world is an old case,” he said. “Why is the United States always trying to use force to implement its agendas?”….

“It is always the same two teams, but all that changes is the ball,” he said in an interview. “They are just laughing at their own people.” Continue reading Neither Republicans nor Democrats learned the real lesson of Benghazi →

![]()

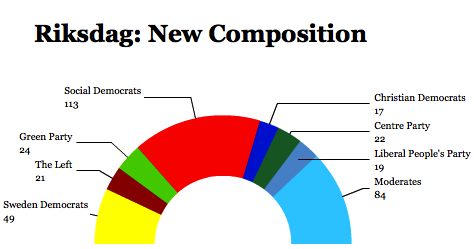

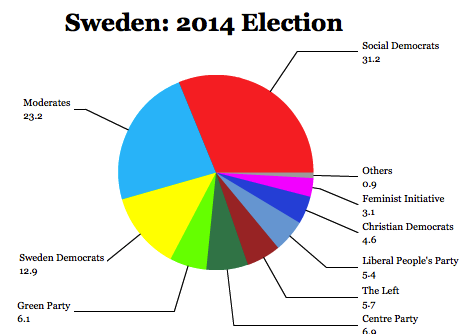

If the big loser of the election was Reinfeldt’s center-right Moderata samlingspartiet (Moderate Party), which lost 23 seats, the big winner was the far-right, anti-immigrant Sverigedemokraterna (SD, Sweden Democrats), which gained 29 seats on a platform of limiting Sweden’s generous asylum policy that in 2014 is expected to welcome more than 100,000 refugees to the country, many from war-torn Syria and Iraq. It’s a point of pride for Reinfeldt, presumably, that he spent much of the campaign extolling the compassionate values of his government, even if those costs limited his ability to promise greater welfare spending.

If the big loser of the election was Reinfeldt’s center-right Moderata samlingspartiet (Moderate Party), which lost 23 seats, the big winner was the far-right, anti-immigrant Sverigedemokraterna (SD, Sweden Democrats), which gained 29 seats on a platform of limiting Sweden’s generous asylum policy that in 2014 is expected to welcome more than 100,000 refugees to the country, many from war-torn Syria and Iraq. It’s a point of pride for Reinfeldt, presumably, that he spent much of the campaign extolling the compassionate values of his government, even if those costs limited his ability to promise greater welfare spending.