As expected, after years of negotiation, Colombia finally has a peace deal with a group of Marxist guerrillas that have been waging war against the central government for over a half-century. ![]()

In Havana on Wednesday, Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos and leftist guerrilla commander Timoleón Jiménez came to a final understanding on a peace deal that could, at long last, end the insurrection of the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), following a four-year process that began in Oslo in 2012, that dominated the 2014 general election and promises to cast a long shadow on upcoming elections in 2018. A ceasefire is set to take effect next Monday.

The deal hopes to end over 50 years of violent conflict between the Colombian state (and often, right-wing paramilitary forces) and FARC, closing a chapter of brutality that stretches back to the 1948 assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a popular presidential candidate, the Bogotazo riots the followed, the ensuing decade of ’La Violencia’ and Colombia’s descent into cartel-fueled drug conflict in the 1980s and 1990s.

Next, however, the Santos government has to win a national referendum on the deal to be held on October 2.

The headlines are congratulatory now, but it’s not going to be an easy campaign to win.

In addition, the ‘Yes’ side must constitute at least 13% of all voters, adding a secondary threshold. So if turnout isn’t high enough, the referendum will not pass. Even if it does win, however, the vote alone will not necessarily secure the peace deal’s future, and it will take years (and likely millions in funding) to normalize peace in Colombia. That includes securing 7,000 rebel guerrillas who have preliminary agreed to disarm. Moreover, the deal also includes a late-breaking and controversial provision that guarantees at least 10 seats in the Colombian congress to a FARC-affiliated political movement through at least the year 2026.

The Colombian government’s position has always been that any peace agreement should be ratified by voters in a special referendum; FARC leaders instead preferred a special constituent assembly. The next five weeks across Colombia will show why they’ve been so tenacious about subjecting the peace deal to a popular vote. There’s no doubt that Santos wants to call the vote relatively quickly to prevent an even longer campaign to discredit his administration’s efforts. First, though, the Santos administration must make public the exact terms of the deal, and it must formally win an internal FARC vote. Every little detail of the deal’s terms and conditions will be potential fodder for derailing it.

As anxious, pro-European Brits might warn, not every issue should necessarily be subject to popular referendum. That’s especially true in a representative democracy, where voters elect professional politicians to make, change and enact laws. That’s especially true in cases where a minority can take away rights from a majority — whether it’s the economic rights that come with EU membership or basic marriage equality for gay men and women. Or, in Colombia’s case, securing special rights and privileges that will induce FARC’s former guerrillas to give up violent conflict in favor of everyday politics.

Moreover, since the moment Santos announced plans to negotiate with FARC, his predecessor, Álvaro Uribe, has bitterly opposed him.

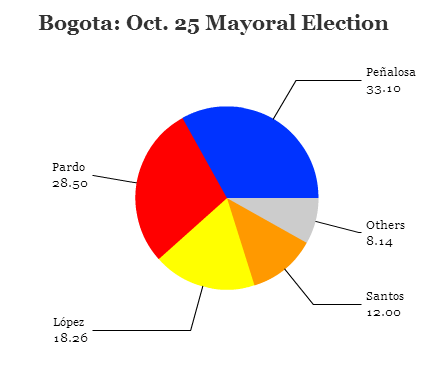

As Uribe’s defense secretary, Santos seemed set to follow Uribe’s hard-line, no-compromise course against FARC. Once elected in 2010, however, Santos diverged, drawing Uribe’s ire and a challenge in the form of a new conservative political party, Centro Democrático (CD, Democratic Center), which thrived in the 2014 parliamentary elections. Uribe’s candidate, Óscar Iván Zuluaga won the first round of the presidential election in May 2014 and only lost the runoff by a narrow six point margin a month later (owing his success more for his emphasis on economic growth than for his skepticism about the peace process). The 2014 runoff vote, in which Santos barely won an absolute majority (50.95%) is evidence for the broad notion that majority of Colombians can be mobilized in support of the peace deal.

But Uribe and his allies will stop at nothing to thwart the peace deal at the ballot box. Most Colombians seem well-disposed to the Santos approach, weary to end the chapter of far-left guerrilla rebellion and far-right military reprisals. The deal contains controversial aspects, including the potential amnesty of FARC rebels, and Uribe will be certain to emphasize the most unpopular elements of the deal.

Andres Pastrana, Uribe’s Conservative predecessor as president, also tried to effect peace negotiations with the FARC, but like Uribe, he opposes the current deal, this week calling it a ‘coup d’etat against justice.’ Both Uribe and Pastrana will argue that a rejection at the ballot box will make possible renegotiation and, potentially, a tougher deal for FARC rebels. But it’s hard enough to know whether FARC guerrillas will universally accept the terms of the current deal, let alone negotiate in good faith after rejection by voters.

WIthout uribismo, the Colombian government would never have been in such a great negotiating position, it’s true. Uribe’s controversial military (and US-backed) approach essentially defeated FARC as a serious threat and challenge to the government. Though Uribe faces accusations of human rights abuses, today’s peace talks directly result from his government’s victories over FARC.

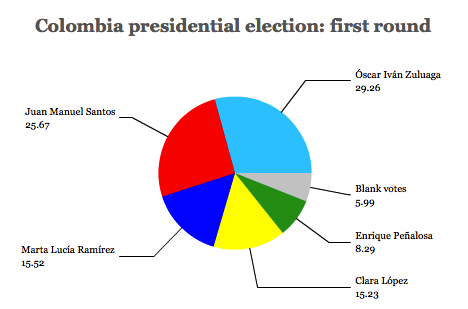

If Santos wins the referendum and signs the peace deal, it will be the most important policy achievement of his two-term presidency. But, with less than two years to go, Santos is massively unpopular as Colombians blame him for a struggling economy and a much devalued peso. Earlier this year, Santos lost the support of the largest party in his coalition, the Partido Liberal Colombiano (PLC, Colombian Liberal Party), and several figures from within the wider pro-Santos camp are already competing for the 2018 elections. Zuluaga, who may run again in 2018, will obviously campaign vigorously against the peace deal. But even Santos’s own vice president, Germán Vargas Lleras, the leader of the liberal, center-right Cambio Radical (Radical Change), and one of several leading 2018 contenders, has backed away from the peace process. Polls generally give the pro-deal camp a narrow lead, but not by much.

Other popular 2018 contenders less politically close to Santos will be in the pro-deal camp. Sergio Fajardo, a former Medellín mayor and governor of Antioquia, is likely to run as the candidate of the Partido Verde (Green Party). So might the left-wing Gustavo Petro, a former Bogotá mayor and M-19 guerrilla. Uribista allies tried to remove Gustavo Petro, a former M-19 guerrilla, as Bogotá mayor (traditionally, the second-most important elected post in Colombia) in 2013 and 2014, ostensibly over the issue of garbage removal. It took a ruling from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to reinstate Petro as mayor.

Petro’s example — the M-19 disarmed years ago and never represented the same level is that as FARC — shows just how radioactive, for both sides, the amnesty and political participation aspects of a peace deal could be. Notwithstanding Santos’s promises, a significant portion of the Colombian political elite will be incredibly wary of the possibility that former left-wing rebels could one day gain power through the political process. The 2018 elections, ultimately, will represent a second-run referendum on the peace deal. Even a vote for peace in October, therefore, doesn’t guarantee the peace process’s ultimate success.