Lithuanians are voting today to select new members of the Seimas, the country’s 141-seat unicameral legislature.

After four years of budget-crushing austerity and slow economic recovery under Andrius Kubilius, the longtime leader of Lithuania’s center-right Tėvynės sąjunga – Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai (TS-LKD, Homeland Union — Lithuanian Christian Democrats) appears headed for defeat.

Under the two-round parallel voting system, voters choose 70 seats by proportional representation (all of which will be determined today) and 71 seats directly in individual districts (many of which will proceed to a second round on October 28). After today, though, we should have a good idea of who will win the largest number of seats.

Throughout much of the campaign, the longtime center-left Lietuvos socialdemokratų partija (LSDP, Social Democratic Party of Lithuania) looked set to emerge as the largest party. But the most recent poll shows that it’s essentially tied with the more populist Darbo Partija (DP, Labour Party).

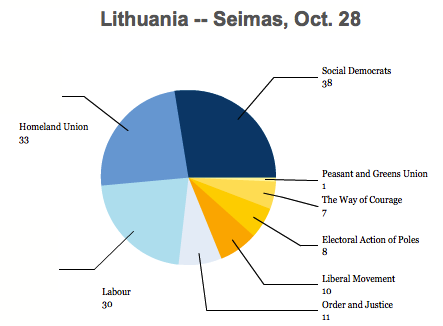

An October 10 poll showed the Social Democrats with 16.9% of the vote to just 15.8% for Labour. Both parties have joined an electoral pact, along with a third party, Tvarka ir teisingumas (TT, Order and Justice), which garnered 8.2% in the poll. Homeland Union won just 7.6%. The socially and free-market liberal Liberalų Sąjūdis (LRLS, Liberal Movement) won 5.8% — the only other party to garner over 5%, the threshold for a party to enter the Seimas on the proportional representation vote.

It seems certain that the two most important individuals to drive Lithuanian policy over the next four years (the Seimas has a fixed term) will be the leader of the Social Democrats, Algirdas Butkevičius (pictured above, right), who will likely become prime minister, and the leader of the Labour Party, Viktor Uspaskich (pictured above, left). The third party in the electoral pact, Order and Justice, is essentially a personality-driven vehicle for its leader, Rolandas Paksas (pictured above, center), and it has veered both left and right.

Butkevičius and his allies have promised to relax some of the budget austerity that has brought Lithuania’s deficit down from nearly 10% of GDP to near the European Union cap of 3%. That has caused some concern among bondholders and EU leaders, who have largely applauded Kubilius’s government and rewarded Lithuania with relatively low bond rates. After a nearly disastrous 2008-09, when Lithuania’s economy collapsed by nearly 15%, GDP growth has now largely returned to Lithuania — 6% growth in 2011. Although the Baltics have largely been held up as showcase examples for budget austerity (despite the protestations of Paul Krugman), unemployment remains staggeringly high at nearly 13%, and both Butkevičius and Uspaskich have said their chief priority will be creating jobs.

Although Lithuania is not hampered by the terms of any EU-based or International Monetary Fund loans, its government has been nudging the country toward adopting the euro, which necessitates getting Lithuania’s budget deficit within 3% of GDP, among other financial benchmarks.

Butkevičius, throughout the campaign, has called for the introduction of a progressive income tax and minimum salaries, and he’s also questioned the rapid accession of Lithuania into the eurozone. But it’s difficult to know where the bluster ends and real policy changes would begin. Butkevičius, a former finance minister in the Social Democrat-led government from 2004 to 2008, has already started to back away from some of his more populist stances.

Throughout Europe this year, we’ve seen anti-austerity candidates win elections on the strength of ‘pro-growth’ policies, only to realize in office that financial constraints restrict their maneuverability. We’ve seen this in Greece, in France (where president François Hollande’s popularity is already sinking) and in the Netherlands (where the anti-austerity Labour Party looks set to join a coalition with budget-cutting prime minister Mark Rutte).

It’s doubtful that tiny Lithuania would be the exception — so a Butkevičius-led government would probably run into many of the same constraining dynamics.

But in addition to the populist rhetoric, there’s more cause for worry — from the two individuals that Butkevičius will likely join in his coalition. Continue reading Meet the new power threesome of Lithuania: Algirdas Butkevičius, Viktor Uspaskich and Rolandas Paksas →

![]()