On the last full weekend of May, European voters in 28 member-states with a population of over 500 million will determine all 751 members of the European Parliament.

The political context of the 2014 parliamentary elections

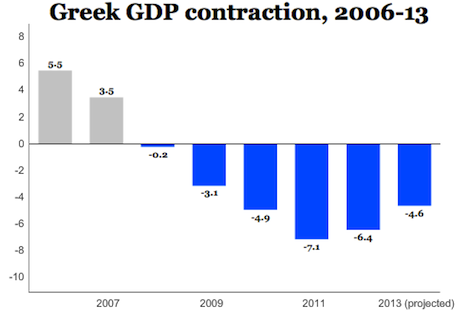

Since the last elections in June 2009, the European Union has been through a lot of ups and downs, though mostly just downs. After the 2008-09 financial crisis, the eurozone went through its own financial crisis, as bond yields spiked in troubled Mediterranean countries like Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal with outsized public debt, sclerotic government sectors and economies operating near zero-growth. Eastern European countries, facing sharp downturns themselves, and a corresponding drop in revenues, implemented tough budget cuts and tax increases to mollify bond markets. Ireland, which nationalized its banking sector, faced similar austerity measures. European Central Bank president Mario Draghi’s promise in the summer of 2012 to do ‘whatever it takes’ to maintain the eurozone marked the turning point, ending over two years of speculation that Greece and other countries might have to exit the eurozone. Many countries, however, are still mired in high unemployment and sluggish growth prospects.

* * * * *

RELATED: The European parliamentary elections are really four contests

RELATED: Here come the Spitzenkandidaten! But does anybody care?

RELATED: A rogues’ gallery of the EU’s top 13 parties

RELATED: An interview with Greek-German MEP Jorgo Chatzmarkakis

RELATED: The US perspective on the European parliamentary elections

RELATED: A detailed look at the European parliamentary results

(part 1)

RELATED: A detailed look at the European parliamentary results

(part 2)

RELATED: The mother-of-all-battles over

European integration has begun

* * * * *

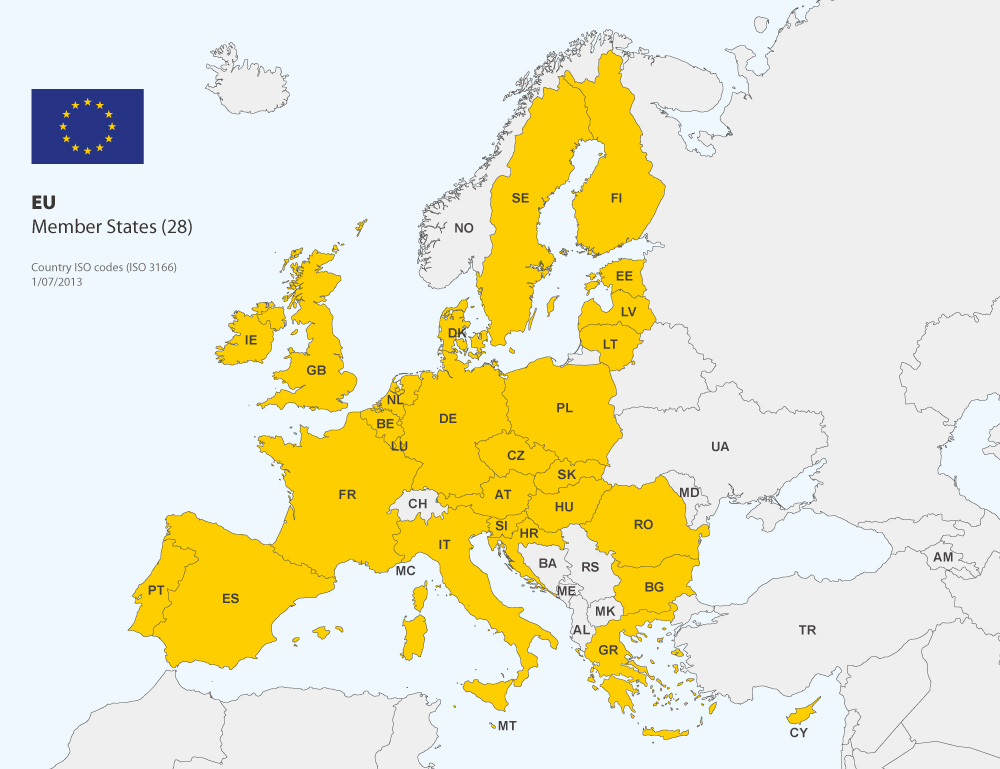

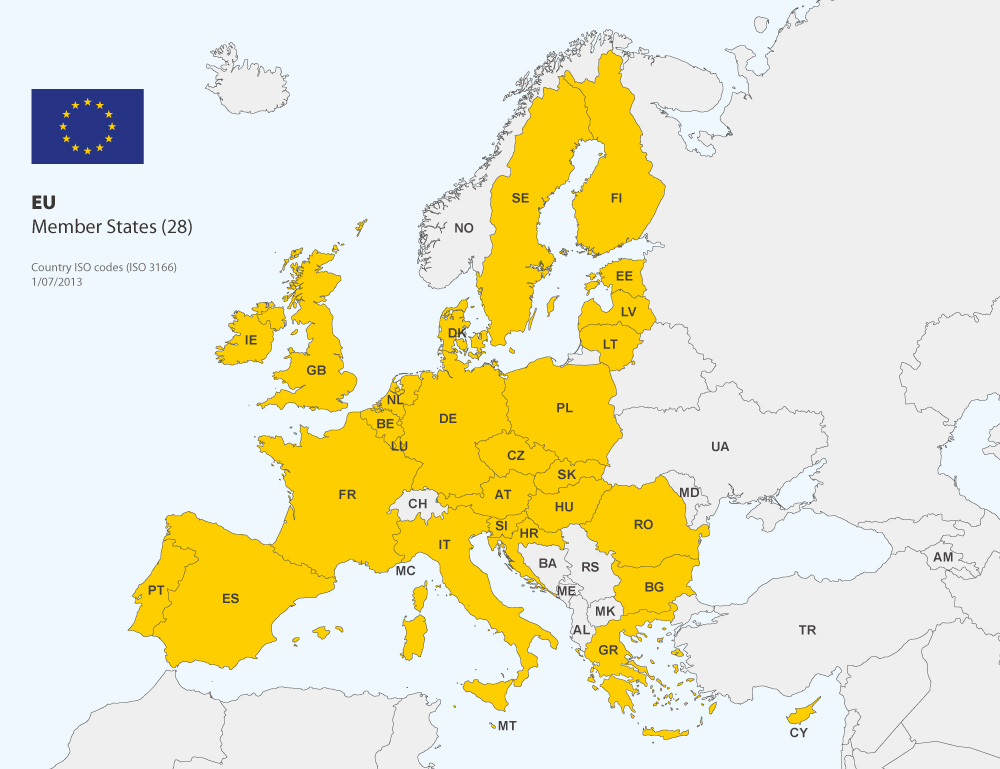

One new member-state joined the European Union, Croatia, in July 2013, bringing the total number to 28, though Iceland, Serbia and Montenegro all became official candidates for future EU membership:

Politically speaking, since the 2009 elections, only two of the leaders in the six largest EU countries are still in power (Polish prime minister Donald Tusk, a centrist, and German chancellor Angela Merkel, a Christian democrat) reflecting a climate that’s been tough on incumbent governments. Spain and the United Kingdom took turns to the political right, and France and Italy took turns to the political left, but none of those governments seems especially popular today — and each of them will face a tough battle in the voting later this month.

Of course, that’s only if voters even bother to turn out. Since the European Parliament’s first elections in 1979, turnout has declined in each subsequent election — to just 43.23% in the latest 2009 elections:

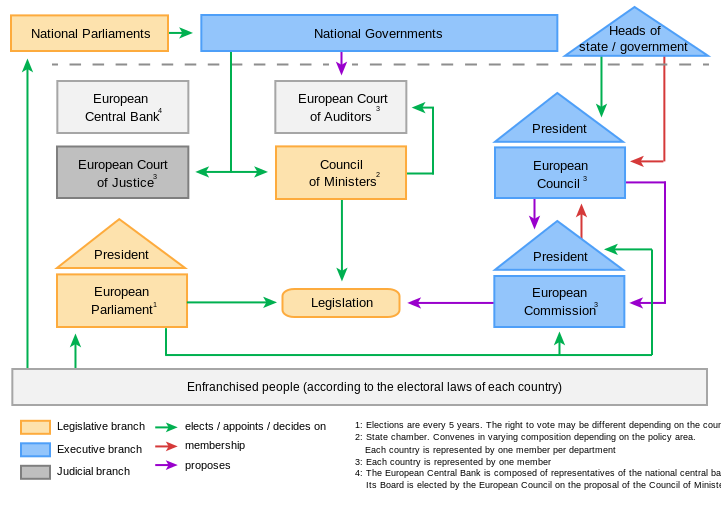

At the European level, the Treaty of Lisbon, a successor to the ill-fated attempt to legislate a European constitution in the mid-2000s, took effect in December 2009, scrambling the relationships among the seven EU institutions.

At the European level, the Treaty of Lisbon, a successor to the ill-fated attempt to legislate a European constitution in the mid-2000s, took effect in December 2009, scrambling the relationships among the seven EU institutions.

The elections, which will unfold over four days between May 22 and May 25, are actually about much, much more than just electing the legislators of the European Union’s parliamentary body, which comprises just one of three lawmaking bodies within the European Union.

A primer on the EU institutions

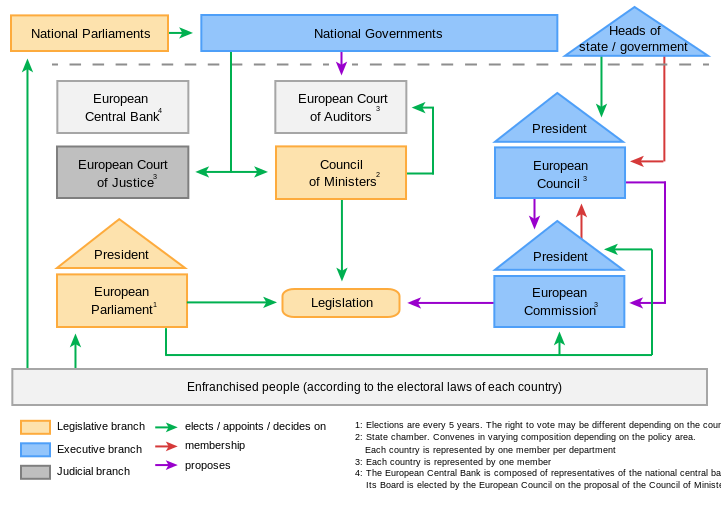

In brief, those seven institutions are as follows:

The European Parliament, first elected in 1979, is the sole institution whose members are elected directly by voters in the European Union. Through subsequent EU treaty negotiations, it has won an increasing amount of power, including budget authority. Today, generally speaking, just about all EU legislation is considered by the parliament, though unlike most national parliaments, it doesn’t have the right of legislative institution, which is reserved solely for the European Commission. The parliament can amend and reject legislation by a simple majority, but it cannot introduce it.

With the Council of the European Union (described below), it forms the entire European parliamentary system. The Lisbon Treaty establishes that almost all EU legislation is now enacted by a process formerly known as the ‘co-decision procedure,’ or the ‘Community method,’ whereby legislation is proposed by the European Commission, and thereafter considered by both the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union.

The European Parliament also has certain oversight powers over the Commission. The Commission president and each of the other commissioners must be approved by a majority, and a two-thirds majority of the European Parliament can force the Commission to resign. This, by the way, isn’t hypothetical — the Commission of former Luxembourg prime minister Jacques Santer (from 1995 to 1999) resigned after EP pressure with respect to corruption allegations.

Though its plenary sessions meet in Strasbourg, France, much of its work takes place in Brussels, where most parliamentary and committee sessions are held. Further administrative offices are located in Luxembourg.

The Council of the European Union, not to be confused with the European Council, is the council of ministers of the 28 nation-states most relevant to a particular piece of EU legislation. For example, if the European Parliament is considering legislation with respect to the environment, the Council is just the group of 28 environmental ministers at the national level. It’s organized on a one-state-one-vote basis. The presidency of the Council rotates every six months among the EU member-states — it’s currently held by Greece, and it will be held by Italy starting July 1.

Like the European Parliament, it cannot introduce legislation, but it can amend or reject it. Unlike the European Union, however, it must adopt legislation by ‘qualified majority voting.’ In a process meant to be simplified by the Lisbon Treaty, however, this has largely been replaced, beginning later in 2014, with ‘double majority voting’ — legislation must win the approval of at least 55% of the member-states, representing at least 65% of the population of the European Union.

The Council, insofar as it includes the 28 member-state foreign ministers, also has responsibility for EU foreign policy, the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), though EU action in foreign policy requires unanimity. Moreover, following the creation of the new high representative position by the Lisbon Treaty, the European Council appoints the chief EU foreign policy official. (Until the Lisbon Treaty, foreign policy was one of three ‘pillars’ of the European Union, joining community/single market matters and justice matters).

The European Council was an informal institution until the Lisbon Treaty, which enshrined it as a formal institution. Like the Council, it’s organized on one-state-one-vote principle, and it’s comprised of the heads of state and/or the heads of government of each of the 28 member-states of the European Union. Unlike the Council, the European Parliament and the Commission, the European Council has no formal role in the legislative process. Instead, it provides high-level strategic guidance from national leaders to the European Union.

Though it’s only recently gained official institutional status, the group of European national leaders has always been responsible for driving the integration processor the past half-century, including:

- the 1957 Treaties of Rome, which established the initial European Economic Community;

- the 1985 Schengen Treaty that eliminated national borders and provided free movement throughout most of the European Union (excepting the United Kingdom and Ireland, but including non-EU members Norway, Switzerland and Iceland);

- the 1986 Single European Act that created the free-trade customs union and single market that Europe knows today;

- the 1992 Maastricht Treaty that formed the single currency through the mechanism of economic and monetary union;

- the 1997 Amsterdam Treaty and 2001 Nice Treaty thatfurther expanded European integration, particularly with respect to foreign policy, economic and monetary union and justice matters; and

- the 2007 Lisbon Treaty that reorganized the EU institutions.

Notably, all EU treaties require unanimity — in 2011, British prime minister David Cameron refused to sign an EU fiscal compact treaty that would have obligated, generally, each EU member-state retain a budget deficit of less than 3% of GDP. After Cameron’s veto, many EU states, particularly eurozone members, entered into the fiscal compact anyway, as an agreement that ranks below the status of an EU treaty.

Meetings of the European Council — ‘summits’ — occur at least four times a year. When it comes to routine decision-making, the European Council also uses qualified majority voting, though it too switches to the 55/65 double majority voting in 2014.

The Lisbon Treaty also gave the European Council the power to elect its own president to serve for a two-and-a-half year term (subject to a one-time renewal), arguably creating for the first time a ‘president of Europe,’ though there remains remains significant and, sometimes, unclear overlap with the role of the European Commission president. The Council elected former Belgian prime minister Herman Van Rompuy (pictured above) as the first Council president.

The Lisbon Treaty and created the position of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, with the idea of creating one officer responsible for EU-level foreign policy. Former British Labour politician Catherine Ashton (pictured above) was elected the first high representative.

Both positions will fall vacant later this year, and the European Council will decide on their replacements.

In addition, the European Council appoints, also by double majority, the president of the European Central Bank. It has historically appointed the European Commission president as well (with the European Parliament approving the Commission president), though under the Lisbon Treaty, the European Council proposes a European Commission president, and the European Parliament elects the president. Furthermore, the Lisbon Treaty instructs the European Council to ‘take into account’ the parliamentary election results.

No one really knows yet what, in practice, this means, and it’s become a major focus of European debate.

The European Commission is the closest thing that the European Union has to an executive body, and its president, since the era of former Commission president Jacques Delors, has been generally viewed as the chief executive of the European Union (though the introduction of a new European Council president has called that into question).

The Commission functions like a cabinet, with 28 commissioners (one for each member-state) responsible for a given portfolio. The president is proposed by the European Council and elected by the European Parliament, as noted above, and a Commission can be forced to resign in mass by a two-thirds vote of the European Parliament.

Generally, the Commission is responsible for enforcing EU legislation, in league with national governments and a growing bureaucracy and numerous agencies with enforcement powers. When politicians rail against ‘Brussels’ throughout Europe, they usually mean the Commission, which is based in Brussels, and which carries out the day-to-day affairs of the European Union. The Commission is essentially unelected — the president is indirectly elected and the other 27 individual commissioners are named by national governments. That’s given critics of the European Union the opportunity to note the Commission’s lack of democratic accountability. As with the process for enacting treaties, the unelected Commission is one of the main issues when critics speak of the European Union’s democratic deficit.

As noted above, it’s also responsible for proposing new legislation. Generally speaking, the Commission can recommend regulations, laws that are directly applicable to each member-state, and directives, laws that set forth binding standards but otherwise leave member-states free to achieve the standards.

Since 2004, former center-right Portuguese prime minister José Manuel Barroso has served as the Commission president. Within six months of the European parliamentary elections, however, Barroso’s Commission will expire — meaning that the European Council and the European Parliament will have to appoint and approve a new Commission. For the first time in 2014, each major family of European parties has nominated a candidate for Commission president, with the idea that the candidate of the leading group should become the next president. National leaders, including German chancellor Angela Merkel, have pushed back against this idea, refusing to concede that the next Commission president should be the candidate of the leading party/group nor that the next Commission president should even come from among the candidates running in the parliamentary elections.

The European Central Bank, established in 1998 by the Amsterdam Treaty and headquartered in Frankfurt, is the central bank that administers European monetary policy, attempts to maintain price stability, establishes eurozone interest rates and otherwise issues euro banknotes. Its role has featured prominently in the current eurozone sovereign debt crisis, and while it doesn’t have quite the overwhelming authority of a national central bank on the same level as, say, the Bank of England or the US Federal Reserve, it’s grown into a powerful institution that can, with the word of its president, move markets.

As noted, the European Council appoints the ECB president. Under Draghi, its president since November 2011, the ECB has become the central player in the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), designed to provide bailouts to troubled eurozone countries through loans and other instruments and to intervene in primary and secondary debt markets to promote financial stability.

The European Court of Justice, which was established in 1952 and sits in Luxembourg, predates the formal European Economic Community. It’s the ultimate arbiter of interpreting EU law across all 28 member-states, and it’s comprised of 28 judges, one per member-state, though it hears cases in smaller panels (of three, five or 13). Its rulings on EU law are final, and cannot be appealed to national courts (and though final national court decisions cannot be appealed to the ECJ, many national courts routinely refer issues of EU law to the ECJ). Confusingly, perhaps, it is not related to the European Court of Human Rights.

Finally, the European Court of Auditors, was established in 1975 to investigate and audit the other EU institutions. Like the ECJ, it’s composed of one member from each member state.

Confused yet? Here’s a chart from Wikipedia that sets forth the EU political structure:

The parliament’s composition

Each member-state is allotted a certain number of seats in the European Parliament on the basis of population, ranging from 96 (in Germany) to just six in the smallest member-states.

Though each member-state is responsible for the voting system that chooses its representative to the European Parliament, member-states must use proportional representation to award the seats, either by means of party-list or single-transferable-vote, with the electoral threshold, if any, not to exceed 5%.

While national parties fight to win parliamentary seats at the national level, ‘families’ of parties have developed at the supranational level, and the European Parliament is generally divided into blocs that align with those party families.

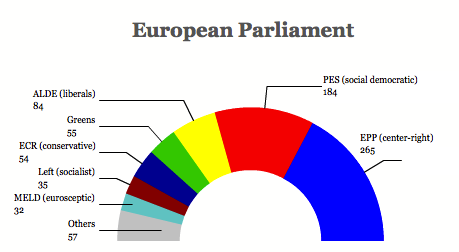

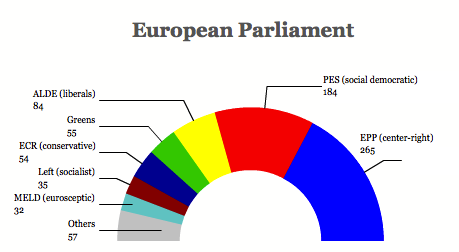

Here’s the current composition:

The European People’s Party (EPP) currently controls the largest bloc of seats in the European Parliament (265), and it’s been the largest party in the European Parliament since 1998, though polls show it might lose that position after the 2014 vote. Moreover, members of its parties currently control 12 out of 28 national governments in Europe and 13 out of 28 seats in the European Commission.

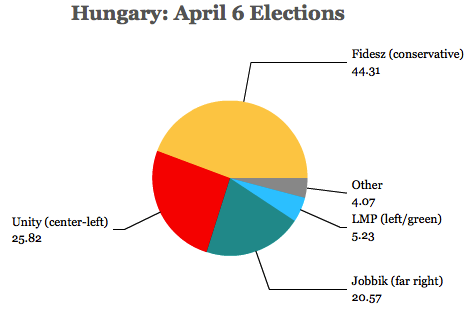

It’s generally comprised of Europe’s traditional center-right and Christian democratic parties, including the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), Bulgaria’s Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), Estonia’s Pro Patria and Res Publica Union (IRL), France’s Union for a Popular Movement (UMP), Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), Greece’s New Democracy (ND), Hungary’s Fidesz, Ireland’s Fine Gael (FG), Luxembourg’s Christian Social People’s Party (CSV), Poland’s Civic Platform (PO), Portugal’s Social Democrats (PSD), Spain’s People’s Party (PP), and Sweden’s Moderate Party.

Its candidate for Commission president is Jean-Claude Juncker (pictured above), the former longtime prime minister of Luxembourg, and the former president of the Eurogroup, an advisory board consisting of the finance ministers of all 18 eurozone states.

Its candidate for Commission president is Jean-Claude Juncker (pictured above), the former longtime prime minister of Luxembourg, and the former president of the Eurogroup, an advisory board consisting of the finance ministers of all 18 eurozone states.

Recent polls show that EPP parties will largely lose ground in the elections. Forecasts show that the EPP will win between 197 and 222 seats, meaning that it might still emerge as the largest bloc in the European Parliament.

The Party of European Socialists (PES) currently controls 184 seats, and between 1979 and 1999, it and its predecessors were the dominant political bloc in the European Parliament. In the European Parliament, the PES is known as the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D). Its members hold seven positions in the Commission and control 10 national member-state governments.

Its constituent parties include most of Europe’s tradition center-left and social democratic parties, including Austria’s Social Democrats (SPÖ), Belgium’s Socialists (PS), the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), the Czech Social Democrats (ČSSD), France’s Socialists (PS), the German Social Democrats (SPD), Greece’s Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), Ireland’s Labour Party, Italy’s Democratic Party (PD), Luxembourg’s Socialist Workers’ Party (LSAP), Malta’s Labour Party, the Dutch Labour Party (PdvA), Portugal’s Socialists (PS), the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), the Swedish Social Democrats (SAP) and the British Labour Party.

Its Commission presidential candidate is Martin Schulz (pictured above), a German Social Democrat who currently serves as the European Parliament president.

Polls show that, for the first time in over a decade, the PES has a real shot of supplanting the EPP as the largest bloc in the European Parliament, with forecasts of winning between 193 to 226 seats.

The Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party (ALDE) is the third-largest bloc, and it features many of Europe’s economically liberal parties. Though it has just 84 seats in the European Parliament, its parties hold eight positions on the European Commission.

Its constituent members include some of the following national parties: Denmark’s Venstre – Liberal Party, the Estonian Reform Party, Germany’s Free Democratic Party (FDP), Ireland’s Fianna Fáil (FF), Lithuania’s Labour Party, Luxembourg’s Democratic Party, both the Democrats 66 and the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) in The Netherlands, Romania’s National Liberal Party (PNL), Sweden’s Centre Party and Liberal People’s Party, and the British Liberal Democrats.

Polls show that, despite the collapse of the FDP in Germany, ALDE should still win between 60 and 86 seats. Its Commission presidential candidate is Guy Verhofstadt (pictured above), the former prime minister of Belgium between 1999 and 2008 — and a contender within the European Council in 2004 to become the Commission president.

The European Green Party (EGP) currently holds 55 seats in the European Parliament, and its members include many of Europe’s leading green parties, such as the Austrian Greens, France’s Europe Ecology/The Greens, Germany’s Alliance ’90/The Greens, Sweden’s Environmental Party/Greens.

Ska Keller, a German green, and José Bové, the French anti-globalization activist, are both running as the Green candidate for Commission president.

Polls show that it may lose support, winning between just 34 and 51 seats.

The Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (AECR) currently holds 54 seats, and it’s an alternative group of center-right parties that lean toward more social and economic conservative ideologies and, often, slightly eurosceptic positions. Its members include the Czech Civic Democrats (ODS), Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS), and the British Conservative Party. The AECR, as a party that leans toward the prerogative of national governments, isn’t fielding a Commission presidential candidate.

Polls show that it will win between 35 and 55 seats.

The Party of the European Left (PEL) currently holds just 35 seats, but it includes many of the staunchest anti-austerity leftist and far-left parties in Europe. Its members include the Danish Red-Green Alliance, the French Left Front, Germany’s Left Party, Greece’s SYRIZA, Ireland’s Sinn Féin and Spain’s United Left (IU).

Its presidential candidate is the Greek opposition leader Alexis Tsipras, and its MEPs sit as part of the he European United Left–Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) group.

Polls show that it is likely to make gains on the basis of Europe’s stagnant economic growth, with forecasts to win between 47 and 61 seats.

The Movement for a Europe of Liberties and Democracy (MELD), which sits in the European Parliament as Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD), is a firmly right-wing eurosceptic group. Its members include the Danish People’s Party, The Finns Party, Italy’s Northern League, and the UK Independence Party (though UKIP holds membership only in EFD, not in MELD).

The EFD parties currently hold 32 seats, and polls forecast they will win between 27 and 40 seats.

The remaining MEPs are referred to as the non-inscrits, because they belong to no supranational bloc, and they include some of the most notorious far-right, xenophobic and eurosceptic parties in Europe, including the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), Belgium’s Flemish Interest, France’s Front national (FN), Hungary’s Jobbik, the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV), and the British National Party.

Polls show that they will make extraordinary gains — and leaders like the PVV’s Geert Wilders and the FN’s Marine Le Pen have discussed possibly uniting behind a new European-level front after the elections.

Polls show that the number of non-insrcits will rise to anywhere between 79 and 106.

Election dates and seats

Finally, if you’ve kept up this long, here’s a schedule when each member-state will be voting, how many parliamentary representatives it will elect, and how that compares to the distribution of seats for the prior 2009 elections.

May 22

United Kingdom: 73 (+1)

The Netherlands: 26 (+1)

May 23

Czech Republic: 21 (-1)

Ireland: 11 (-1)

May 24

Italy: 73 (+1)

Slovakia: 13 (–)

Lithuania: 11 (-1)

Cyprus: 6 (–)

Malta: 6 (–)

May 25

Germany: 96 (-3)

France: 74 (+2)

Spain: 54 (+4)

Poland: 51 (+1)

Romania: 32 (-1)

Belgium: 21 (-1)

Greece: 21 (-1)

Portugal: 21 (-1)

Hungary: 21 (-1)

Sweden: 20 (+1)

Austria: 18 (+1)

Bulgaria: 17 (–)

Denmark: 13 (–)

Finland: 13 (–)

Croatia: 11 (N/A)

Slovenia: 8 (+1)

Latvia: 8 (–)

Estonia: 6 (–)

Luxembourg: 6 (–)

![]()

![]()