There’s a neighborhood in Los Angeles, commonly known as Tehrangeles, that is home to up to a half-million Persian Americans, most of whom fled Iran after the 1979 Islamic republic or who are their second-generation children and third-generation grandchildren, all of them American citizens. ![]()

The neighborhood runs along Westwood Boulevard, and it is home to some of the wealthiest Angelinos. But under the executive action that US president Donald Trump signed Friday afternoon, their relatives in Iran will have a much more difficult time visiting them in Los Angeles (or elsewhere in the United States). The impact of the order, over the weekend, proved far deeper than originally imagined last week when drafts of the order circulated widely in the media.

The ban attempts to accomplish at least five different actions, all of which began to take effect immediately on Friday:

- First, the order institutes a ban for 90 days on immigrants from seven countries — Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Somalia and Libya.

- Secondly, the ban initially seemed to include even US permanent residents with valid green cards with citizenship from those seven countries (though the Department of Homeland Security was walking that back on Sunday, after reports that presidential adviser and former Breitbart editor Steve Bannon initially overruled DHS objections Friday). But it also includes citizens of third countries with dual citizenship (which presents its own problems and which the White House does not seem to be walking back).

- Third, it institutes a 120-day freeze on all refugees into the United States from anywhere across the globe and an indefinite ban for all refugees from Syria.

- Fourth, it places a cap of 50,000 on all refugees for 2017 — that’s far less than nearly 85,000 refugees who were admitted to the United States in 2016, though it’s not markedly less than the nearly 55,000 refugees admitted in 2011 (the lowest point of the Obama administration) and it’s more than the roughly 25,000 to 30,000 refugees admitted in 2002 and 2003 during the Bush administration.

- Fifth, and finally, when the United States once again permits refugees, it purports to prioritize admitting those refugees ‘when the person is a religious minority in his country of nationality facing religious persecution.’ It’s widely assumed that this is a back-door approach to prioritizing Christian refugees. More on that below.

In practice, it’s already incredibly difficult to get a visa of any variety if you are coming from one of those countries, with a few exceptions. But formalizing the list is both overbroad (it captures mostly innocent travelers and refugees) and underbroad (it doesn’t include potential terrorists from other countries), and experts believe it will hurt US citizens, US businesses and bona fide refugees who otherwise might have expected asylum in the United States. On Sunday, many Republican leaders, including Arizona senator John McCain admitted as such:

Ultimately, we fear this executive order will become a self-inflicted wound in the fight against terrorism. At this very moment, American troops are fighting side-by-side with our Iraqi partners to defeat ISIL. But this executive order bans Iraqi pilots from coming to military bases in Arizona to fight our common enemies. Our most important allies in the fight against ISIL are the vast majority of Muslims who reject its apocalyptic ideology of hatred. This executive order sends a signal, intended or not, that America does not want Muslims coming into our country. That is why we fear this executive order may do more to help terrorist recruitment than improve our security.

On the campaign trail, Trump initially called for a ban on all Muslims from entering the country; when experts responded that such a broad-based religious test would be unconstitutional, Trump said he would instead extend the ban on the basis of nationality.

Friday’s executive action looks like the first step of institutionalizing the de facto Muslim ban that Trump originally promised (thought it would on its face be blatantly unconstitutional).

Of course, as many commentators have noted, the list doesn’t contain the countries that match the nationalities of the September 2001 hijackers — mostly Saudi Arabia. But it doesn’t contain Lebanon, though Hezbollah fighters have aligned with Syrian president Bashar al-Assad in that country’s civil war. It doesn’t include Egypt, which is the most populous Muslim country in north Africa and home to one of the Sept. 2001 terrorists. Nor does it include Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country. Nor Pakistan nor Afghanistan, where US troops fought to eradicate forms of hardline Taliban government and where US troops ultimately tracked and killed Osama bin Laden.

This isn’t a call to add more countries to the list, of course, which would be even more self-defeating as US policy. But it wouldn’t surprise me if Bannon and Trump, anticipating this criticism, will use it to justify a second round of countries.

In the meanwhile, the diplomatic fallout is only just beginning (and certainly will intensify — Monday is the first full business day after we’ve read the actual text of Friday’s executive order). Already, Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel, citing the obligations of international law under the Geneva Conventions, disavowed the ban. Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau used it as an opportunity to showcase his country’s openness to immigration and welcomed the refugees to Canada. Even Theresa May, the British prime minister who shared a stage with Trump in Washington on Friday afternoon, distanced herself from the ban, and British foreign minister Boris Johnson called it ‘divisive.’

But the most direct impact will be felt in relations with the seven countries directly affected by the ban, and there are already indications that the United States will suffer a strategic, diplomatic and possible economic price for Trump’s hasty unilateral executive order.

Iran, it’s true, is a theocratic and authoritarian country that calls itself the Islamic Republic. But jihadist terrorism in the United States, as practiced by al-Qaeda and now by ISIS and associated groups, is rooted more in the Sunni tradition than Iran’s Shiite tradition. Iran is by far the most populous country captured under the ban, with nearly 80 million people, and the Obama administration had succeeded in lowering tensions, if not suspicions, between the two countries.

The ban hits at an especially precarious time for Iran, with its reformist president Hassan Rowhani up for reelection in May, and with the country only beginning to meet the terms of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) that governs Iranian nuclear capability for the next decade. If one of the key soft-power elements of that Iran nuclear deal was to integrate Iran into the global economy, that goal was already off track. But the US ban — even if temporary — seems set to isolate Iran further. An Iran that feels threatened by its neighbors or by the United States, however, is more likely to seek nuclear weapons in the future. That, in turn, could lead to a nuclear arms race, with the Saudis, the Turks and other attempting to develop their own nuclear programs in the region. More immediately, though, the failure of Iran’s economy could lead to blowback against Rowhani and, possibly, the election of a far more hardline Iranian president. That would not be in the US national interest.

More immediately, Iran’s leaders are now in the process of implementing a reciprocal ban on all American visitors. But closer to home, we’re already reading stories about the hassles faced by Iranian visitors to family here in the United States, of parents separated from children and grandchildren, of husbands separated from wives.

As McCain and many others have noted, the blanket ban on Iraqi refugees and visaholders impairs US efforts in the country to help defeat ISIS. But it also sends a powerful message to Iraqi translators and interpreters, who risked their lives to assist the US military and who depend upon special immigrant visas.

To the extent those SIVs aren’t respected, it will send a powerful incentive to Iraqis and others, now and in the future — the United States cannot be trusted, so don’t bother assisting them. Indeed, some of the first travelers detained under Trump’s order were former translators out of Iraq.

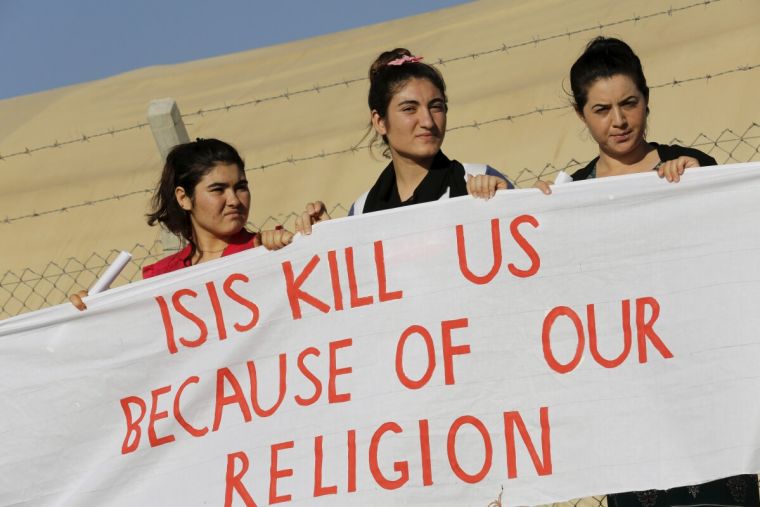

It seems especially cruel to include Iraqis in the ban, considering that much of the chaos in the country, home to 33 million people, stems from the US-led removal of Saddam Hussein in 2003 and subsequent occupation (which still failed to prevent a civil war between 2006 and 2008). ISIS has targeted the Yazidis of northern Iraq, in particular, who worship under the tenets of a pre-Islamic religion with elements similar to Christianity. Nevertheless, the country ban and refugee halt could significantly and disproportionately affect them.

Of course, the ban also fails to distinguish between Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan, the latter a chiefly stable and nearly autonomous region in northern Iraq. Iraqi Kurds have been instrumental in holding off ISIS’s advances and in holding Kirkuk as Iraqi territory — and out of ISIS’s hands. To bar Kurdish businessmen will slow commerce in a region that, for decades, has been fiercely loyal to the United States, and a nascent Kurdish oil industry far more stable than in the rest of Iraq today.

The Iraqi parliament, in a non-binding vote, has already recommended a reciprocal ban on US citizens that, if adopted, would cripple US businesses working in the country’s oil industry. Ironically, even as Trump mused last week about ‘taking the oil,’ his administration’s actions make it more difficult for US businesses to develop Iraqi oil supplies. From a commercial and strategic sense, that only strengthens China, Europe, Iran and others.

If there’s a one area where you can draw a line from the Obama administration to the Trump administration, it’s Syria, where Obama’s refugee policy in the early years of the civil war was truly draconian. Nearly six years after the war began, up to 470,000 Syrians have been killed, over 7.6 million have been internally displaced, and over 4.8 million refugees have fled to Lebanon, Turkey, Europe and elsewhere.

Yet as conservative critics have pointed out, the Obama administration basically put into place a de facto ban on Syrian refugees until last year. The United States accepted just 29 Syrian refugees in fiscal year 2011, 31 in 2012, 36 in 2013 and just 105 in 2014. Though the Obama administration exponentially increased that number (around 1700 were in 2015 and 13,000 in 2016), it’s comparatively low by the standards of the far more generous European and Canadian refugee policies.

Still, it’s not ‘zero,’ as Trump’s policy would require.

Again, to the extent that ISIS developed out of the chaos of the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, the United States is now shutting the door to those it arguably has a moral obligation to help, including religious minorities. As in Iraq, US special forces today — at this very moment — depend on the help of their Syrian partners (especially Syrian Kurds) in the push to defeat ISIS, an effort that was succeeding in both Syria and Iraq. The ban, as it relates to Syria, could ultimately leave the United States with far less diplomatic influence, ceding power instead to Russia and to Iran and other regional actors in fashioning a lasting peace to the ongoing civil war. Experts warn that it could also amount to a recruiting boon for ISIS, feeding into its clash-of-civilizations mentality.

On the same week that Trump propagated his ban, he also directed a raid on al-Qaeda targets in southern Yemen, killing the eight-year-old daughter (an American citizen) of the late radical cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, among other alleged jihadist actors.

Ironically, al-Qaeda operatives, chiefly Sunni, have been de facto allies for the last two years with US-armed Saudi Arabia against the northern Houthi government, chiefly Shiite. The US government, only last December, decided to halt some shipments of US weapons to the Saudi government due to ongoing human rights concerns about how the Saudis have conducted their attacks on Yemen, home to 25 million people, in what is largely seen as a proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Again, to the extent that Yemen has been a target of US bombs over the last two decades (and to the extent that the Bush administration provided support to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh in his war against ‘terrorists’ in southern Yemen), it seems particularly cruel to now close American doors to Yemeni refugees.

The impoverished country, which lacks the natural resources wealth enjoyed by the rest of the countries on the Arabian peninsula, is technically governed by its president since 2012, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, a Sunni and Saleh’s vice president from 1994 to 2012, after Saleh agreed to step down in the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring protests. Houthi rebels, however, now control much of the north of the country and, since January 2015, the capital city of Sana’a. Hadi’s predecessor, Saleh, who was once a Saudi ally, is now aligned with the Houthis and with Iran, which generally supports the Houthi-led government.

Throughout the 2000s, Saleh worked with both the Saudis and the Americans to oppose al-Qaeda’s presence in southern Yemen — though the Saudi royal family and al-Qaeda’s leadership are both Arabian and Sunni, the Saudi government considers the terrorist group a threat to its own control. Often, however, Saleh used American aid not to attack al-Qaeda, but to put down secessionist rebels in Yemen’s south, which until 1990 was an independent (though Soviet-allied) country based in Aden.

In recent years, Yemen has become a battleground for all these groups (and their foreign benefactors) to pursue their contradictory agendas, leaving the country essentially a failed state.

Yemen, too, provides a particularly interesting case for the Trump administration’s new ‘minority religions’ priority rule. Shiites are a slight minority in Yemen vis-à-vis Sunnis — will they receive special treatment under the Trump refugee process? Does it matter if Yemen’s government is toppled by Sunni rebels (with Saudi help)? In Iraq, likewise, most citizens are Sunnis while Shiites dominate the government. Should Iraqi Shiites receive special consideration today, given that they hold so much more political power? Would that change if another Sunni strongman (like Saddam Hussein) took power? These are just two examples of the new questions that this executive order generates, and it’s not clear that Bannon, Trump or anyone else in the White House have thought one second about their answers.

Like Yemen, Somalia has been the target of US destabilization over the last two decades. It’s true that it is one of the most failed states in the world and the al-Shabab terrorist organization has carried out attacks in Somalia, in neighboring Kenya and elsewhere.

But as with the northern Kurdish region of Iraq, the northern region of Somaliland is nearly autonomous from Mogadishu (and it coincides with the borders of what was the former British Somaliland protectorate). While the rest of Somalia (which coincides with the former Italian Somaliland) may be a failed state, Somaliland is far more stable and, indeed, will hold a general election in March, and it’s home to 4.5 million people out of a total ‘Somali’ population of over 12 million. Again, it’s an example of how the Trump order is overbroad.

When the United States backed a British and French effort to oust Libya’s longtime leader Muammar Qaddafi in 2011 as he threatened to crack down on rebels in eastern Libya, the world discovered that Qaddafi left Libya with almost no state institutions or structure to govern the sparsely populated country of just 6 million.

That’s left Libya open to competing tribal militias and ISIS infiltration over the last six years. Though the ISIS threat is receding, competing factions, including one led by Libyan general Khalifa Hifter, a one-time CIA ally and fierce anti-Islamist, now vie for control of a country that has proved ungovernable in the post-Qaddafi era.

Unlike Libya and Somalia, Sudan is relatively stable under the leadership of Omar al-Bashir. A longtime international pariah, even before a widespread genocide in the 2000s in Darfur, Bashir once hosted bin Laden in the 1990s before international and American pressure forced bin Laden to Afghanistan instead. Sudan today is home to nearly 40 million people.

It’s unclear what the ban means for citizens of South Sudan who, until the country’s independence in 2011, were Sudanese citizens. The majority-Christian South Sudan, however, is locked in a civil war between the followers of president Salva Kiir and former vice president Riek Machar. Though it is home to much of the former Sudan’s oil, the civil war and the country’s lack of development and infrastructure has hampered its ability for economic growth, making it one of the poorest countries in the world. That, combined with the ongoing war, makes it one of the top priorities for refugee aid groups worldwide. There remains some uncertainty about border regions between Sudan and South Sudan, and many South Sudanese have fled to refugee camps back in Sudan since independence.

Given that Los Angeles Lakers star Luol Deng and Milwaukee Bucks rookie Thon Maker are both from South Sudan, the NBA has sought clarification from the US State Department about how South Sudanese citizens will be treated under the order.

As you can see I’m far behind reading your interesting articles, I discovered one thing which I think is wrong. In Iraq both the government and about 60% of the population are Shia muslims, so the majority/minority question changes quite a bit in this article…

How are you, I require your insight on this. I highly recommend you contact me straight away: frans.wikman@gmx.com