Amid the chaotic urban anarchy of Karachi and the lawlessness of tribal border areas near Afghanistan, it’s rare that Islamabad becomes the central focus of political instability in Pakistan.![]()

But that’s exactly what’s happening this week in the world’s sixth-most populous country, and if protests against Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif explode into further unrest, it could trigger a constitutional crisis or even a military coup. That Pakistan’s fate is now so perilous represents a serious step backwards for a country that, just last year, marked the completion of its first full five-year term of civilian government and a democratic transfer of power.

Imran Khan (pictured above), the leader of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI, پاکستان تحريک انصاف, translated as the Pakistan Movement for Justice), is leading protests in the Pakistani capital calling for Sharif’s resignation relating to allegations of voter fraud in last year’s national elections. Sharif, in turn, is pressuring the country’s powerful military to guarantee order in Islamabad and the ‘red zone’ — a highly fortified neighborhood where many international embassies and the prime minister’s house are located and where Khan and his supporters have threatened to march if Sharif refuses to step down. Khan has increasingly escalated his demands, and he now seems locked in a high-stakes political struggle with Sharif that could end either or both of their careers.

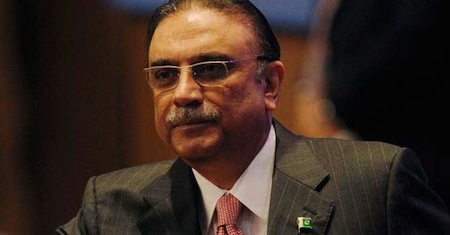

In last May’s parliamentary elections, Sharif’s conservative, Punjab-based Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML-N, اکستان مسلم لیگ ن) ousted the governing center-left, Sindh-based Pakistan People’s Party (PPP, پاکستان پیپلز پارٹی). Khan’s anti-corruption party, the PTI, won 35 seats, the second-largest share of the vote nationally, and the largest share of the vote in regional elections in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the northwestern border region near Afghanistan that is home to nearly 22 million Pakistanis, largely on the strength of Khan’s denunciation of US drone strikes on the region. Though Khan and the PTI hoped for a better result, it was nevertheless their best result by far since Khan entered politics in 1996.

Earlier this week, Khan directed his party’s legislators to resign from of the national assembly and three of the four regional assemblies. (The PTI wouldn’t, after all, be resigning its seats in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where it controls the government).

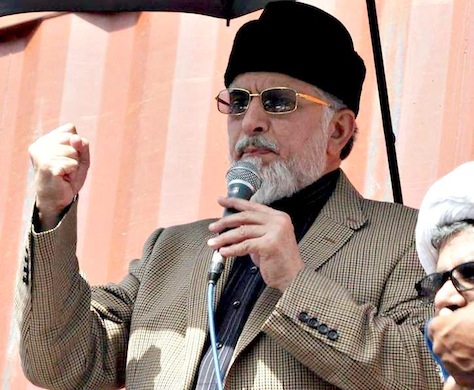

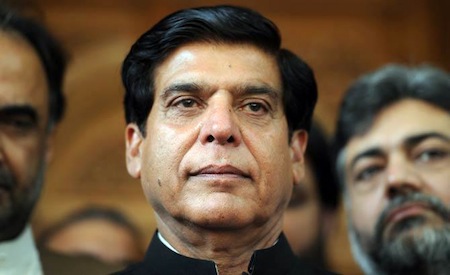

Khan’s protests dovetail with similar protests led by Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri (pictured above), a Sufi cleric and scholar who leads a small but influential party, the Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT, پاکستان عوامي تحريک, translated as the Pakistan People’s Movement). Like Khan’s PTI, the PAT is an anti-corruption and pro-democratic party. Tahir-ul-Qadri, who returned to Pakistan in 2012 after living for seven years in Toronto, has been described as the ‘Anna Hazare’ of Pakistan, in reference to the Hindu social activist who’s fought against corruption in India, and he protested the PPP with equal gusto.

Early Thursday, there were hopes that negotiations among the parties could relieve the political crisis’s escalation, if not wholly end it. But it’s more complicated that, because of the delicate role that the military still plays in the country’s affairs.

You can think of the current tensions in Pakistan as a triangular relationship:

Continue reading Pakistan’s Sharif caught between opposition and military