If anyone had doubts, it’s clear now that Indian prime minister Narendra Modi has a clear grip on his country.![]()

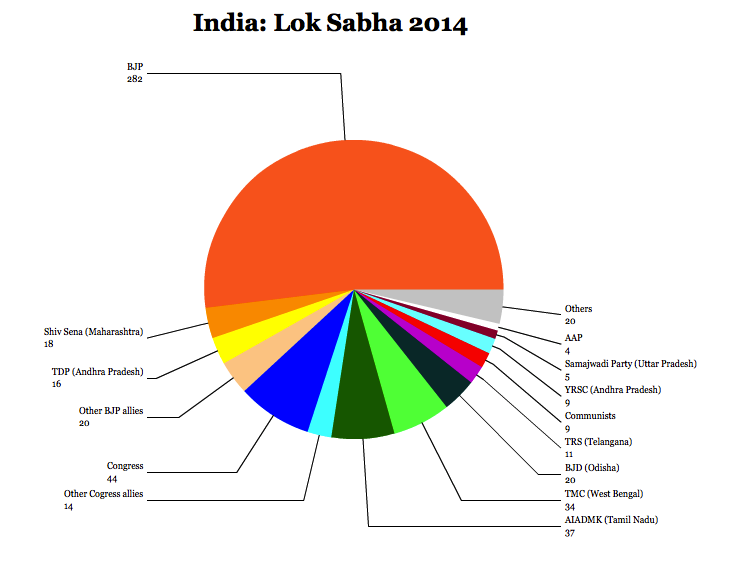

When Modi swept to power in 2014 by capturing the biggest Indian parliamentary majority in three decades, he did so by unlocking key votes in Uttar Pradesh. Ultimately, Modi owed his 2014 majority to the state, which gave him and the Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) 73 of its 80 seats to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament.

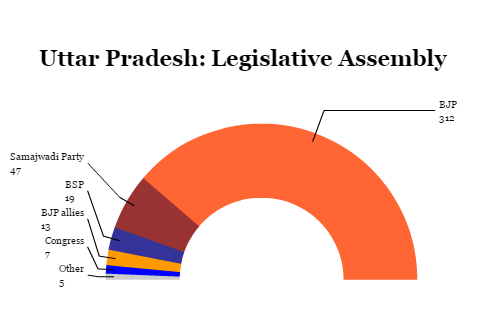

Nevertheless, it was a surprise last weekend — even to Modi’s own supporters — when, after seven phases of voting between February 11 and March 8, officials reported that the BJP won over three-fourths of the seats in the Uttar Pradesh legislative assembly. That’s a landslide, even in the context of a state where voters like to see-saw from one party to the next every five years. The BJP victory marked only the fourth time in history (and the first time since Indira Gandhi’s victory in 1980) that a single party won over 300 seats in the UP legislative assembly, and it bests the earlier BJP record (221 seats in 1991) by just over 90 seats.

A referendum on demonitisation

The victory in Uttar Pradesh, one of five state elections for which results were announced on March 11, amounts to a massive endorsement of Modi (less so of the BJP). Though the 2019 elections are over two years away, the victory will give Modi some comfort that he will win reelection. For now at least, the Uttar Pradesh victory shows just how far behind Modi the opposition forces have fallen.

With over 200 million people, Uttar Pradesh is the most populous state in the country and, indeed, it’s home to more people than all but five countries worldwide.

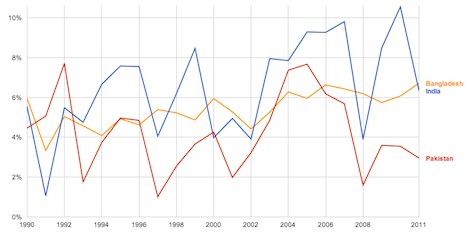

In some ways, Modi’s staggering victory in Uttar Pradesh this spring is even more spectacular than his 2014 breakthrough. After all, Modi was defending a three-year record as prime minister that hasn’t been perfect. Despite winning the biggest parliamentary majority since 1984, the protectionist wing of the BJP has slowed the pace of Modi’s economic reforms. It was only last November that Modi successfully completed a years-long push to reform the goods and sales tax — a landmark effort to harmonize state levies into a single national sales tax, thereby lowering the costs of doing business between Indian states. Those obstacles still exist, as evidenced by the truckers lined up at state borders for hours or days on end.

For all the supposed benefits of the November 2016 demonetisation plan, its rollout was cumbersome, with the sudden removal of 500-rupee and 1,000-rupee bills from circulation in a country where 90% of all transactions are cash transactions, most of which involved the two ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes (equivalent, respectively, to $7.50 and $15.00 in the United States). Though Modi hoped the abrupt step would stem corruption and retard the flow of illicit ‘black money’ that’s evaded taxation, the move also inconvenienced everyday commerce and trade, as ordinary and poor Indians struggled to transition to the new system.

So the state elections — in Uttar Pradesh as well as Uttarakhand, Punjab, Manipur and Goa — were referenda on Modi’s reform push, in general, and demonetisation, in particular.

Modi passed the test, as voters gave his government the benefit of the doubt — and he did it on his own, with the help of his electoral guru, Amit Shah, a longtime aide to Modi during Modi’s years as chief minister in Gujarat and the engineer of the BJP’s victory in Uttar Pradesh in 2014 and, since 2014, the BJP party president.

So personalized was Modi’s campaign that the BJP didn’t even bother naming a candidate for chief minister. So the BJP won a three-fourths majority in India’s largest state without ever telling voters who it intended to serve as the state’s top executive. Speculation initially revolved around Rajnath Singh, the 65-year-old home secretary who once served as chief minister of Uttar Pradesh from 2000 to 2002 and who is himself a former BJP president. But But 57-year-old communications and railways minister Manoj Sinha, who was born in Ghazipur and represents the city in the Lok Sabha, is also a leading contender. Modi and Shah are expected to make a decision by Saturday. Continue reading Modi sweeps state elections in Uttar Pradesh in win for demonetisation