As Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán hopes to consolidate his hold on Hungarian government in the country’s April 6 elections, the Hungarian center/left is uniting in a broad anti-Orbán coalition.

Under the banner of Osszefogas (‘Unity’), five of Hungary’s center-left parties will band together behind the prime ministerial candidacy of Attila Mesterházy (pictured above, center), the leader of Hungary’s largest opposition party, the Magyar Szocialista Párt (MSzP, Hungarian Socialist Party).

The coalition brings together four relatively new groups:

- Együtt 2014 (E14, Together 2014) is a new social democratic party founded in October 2012 by former prime minister Gordon Bajnai, a Socialist who governed Hungary s somewhat of a technocratic caretaker between April 2009 and May 2010, when which Orbán came to power with a supermajority. Bajnai’s government tried to steer a course through crippling budget austerity and an economy that hit its nadir with a 6.8% contraction in 2009. From the outset, Bajnai (pictured above, far left) has advocated a united anti-Orbán front for the 2014 elections.

- Párbeszéd Magyarországért (PM, Dialogue for Hungary) is a green liberal party founded in February 2013 as a breakway faction of Lehet Más a Politika (LMP, Politics Can Be Different), another green party founded in 2009. PM’s leaders are Timea Szabó and Benedek Jávor, the latter an environmental lawyer and botanist. The party has, since March 2013, been allied with E14 in advance of this year’s elections.

- Demokratikus Koalíció (DK, Democratic Coalition) is the party of Ferenc Gyurcsány, prime minister between 2004 and 2009, and it was founded in October 2011 when Gyurcsány (pictured above, center, behind Mesterházy) left the Socialists, taking with him 10 of the Socialists’ 59 seats in the National Assembly. Gyurcsány’s decision to unite under Mesterházy is particularly helpful for the anti-Orbán opposition because Gyurcsány remains more well-known than Mesterházy. Even though Mesterházy led the (disastrous) 2010 electoral effort, Gyurcsány has more governing experience and political canny. Gyurcsány, who came to power at a time when Hungary’s budget deficit was spiraling out of control (even in pre-crisis days), resigned in 2009 after introducing ever harsher budget reforms in line with a 2008 financing agreement with the International Monetary Fund. Gyurcsány’s budget reforms, and his attempt to modernize the Hungarian health-care system, alienated him from his own party.

- The Magyar Liberális Párt (Hungarian Liberal Party) was founded in April 2013 as a pro-European, liberal party by Gábor Fodor, a former education minister in the mid-1990s and an environmental minister in 2007-08. Fodor (pictured above, far right) was the the final leader of the Alliance of Free Democrats/Liberal Party, a predecessor to the current party that divided in 2008, when the liberal coalition lost the last of its 20 seats in the National Assembly.

Though the green LMP hasn’t joined the coalition, the five-party front is demonstrating about as much unity as you could expect — and much more than the alternative, much feared a month ago, that Orbán would take advantage of the disunity to win an outsized supermajority in the National Assembly.

In the current 386-member National Assembly, Orbán’s ruling conservative party, Fidesz – Magyar Polgári Szövetség (Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance) controls 226 seats. Together with its ally, Kereszténydemokrata Néppárt (KdNp, Christian Democratic People’s Party), which today has become more a satellite of Fidesz than a truly independent party, Orbán controls 263 seats. That’s a supermajority of just over two-thirds, and that’s permitted Orbán to introduce constitutional reforms and other laws that have strengthened his hold on power and undermined Hungary’s democratic institutions.

The Socialists control just 48 seats, and the far-right nationalist Jobbik Magyarországért Mozgalom (Jobbik) controls 43 seats.

Under new electoral rules, the National Assembly will be reduced from 386 seats to just 199 seats. Unlike the prior system, where just over half of the seats were determined by proportional representation, the new system tilts slightly more toward plurality districts — 106 seats will be determined in single-member districts by first-past-the-post voting. Another 93 seats will be determined by party-list proportional representation (with a 5% threshold for parties and a 10% threshold for coalitions). In an election with five center-left parties competing against each other as much as against Orbán, Fidesz remained the overwhelming favorite to with the 106 plurality seats. So the unification of the center-left opposition makes a nearly impossible race merely a tough race.

A January 15 IPSOS poll shows Fidesz with around 48% of the vote, the Hungarian Socialists with 27%, Jobbik with 11% (far below the troublingly high 17% it won in the April 2010 elections) and other parties in single digits. But when you add the new Unity coalition totals together, Fidesz leads by a more narrow margin of 48% to 37% (DK and E14 each win 5% of the vote.

If the election were held tomorrow, Fidesz would still win, but the Unity coalition might together win seats that would otherwise fall to Fidesz. In other words, Mesterházy and the united opposition would turn a landslide defeat into a robust defeat.

But is there a way to actually win the election against Orbán? Or does Fidesz have a lock on April’s elections? Continue reading Hungarian left unites, but will it be enough to stop Orbán? →

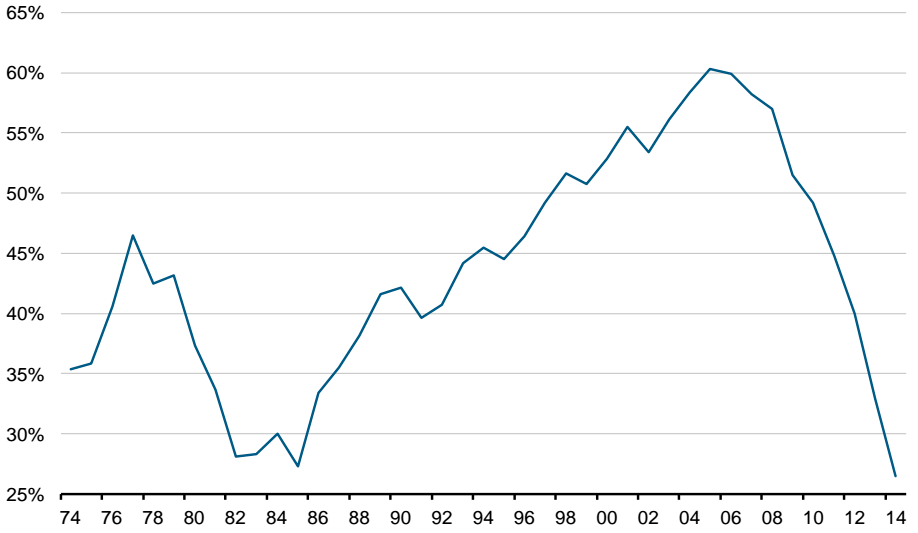

Chart credit to Bank of America.

Chart credit to Bank of America.![]()

![]()