No one has more riding on the outcome of the April 2 presidential runoff in Ecuador than Julian Assange. ![]()

The Wikileaks founder has been shacked up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London since 2012. Officially, Assange is evading an extradition to Sweden to stand trial for sexual assault charges. Ecuador’s outgoing president Rafael Correa granted Assange asylum five years ago, a populist move responding to the eccentric Australian native’s fears that he might ultimately be subjected to the grips of US extradition.

If one-time frontrunner Lenín Moreno, Correa’s former vice president, and the heir to Correa’s self-proclaimed ’21st century socialist’ Alianza PAIS movement, wins Sunday’s election, Assange can rest assured that Ecuador’s government will not revisit that arrangement anytime soon.

But if center-right insurgent Guillermo Lasso has his way, he will evict Assange from from Ecuador’s protections within 30 days of taking office.

Though Assange’s fate is drawing global headlines, Ecuador’s election represents a fascinating showdown between two very different policy views for the country’s future outcome — and a referendum on Correa’s decade-long rule. The result will hold deep consequences for the country, its rule of law, its electorate and Latin America generally. A country of 16 million that, since 2000, has used the US dollar as its currency, Ecuador is today the eighth-largest economy in Latin America.

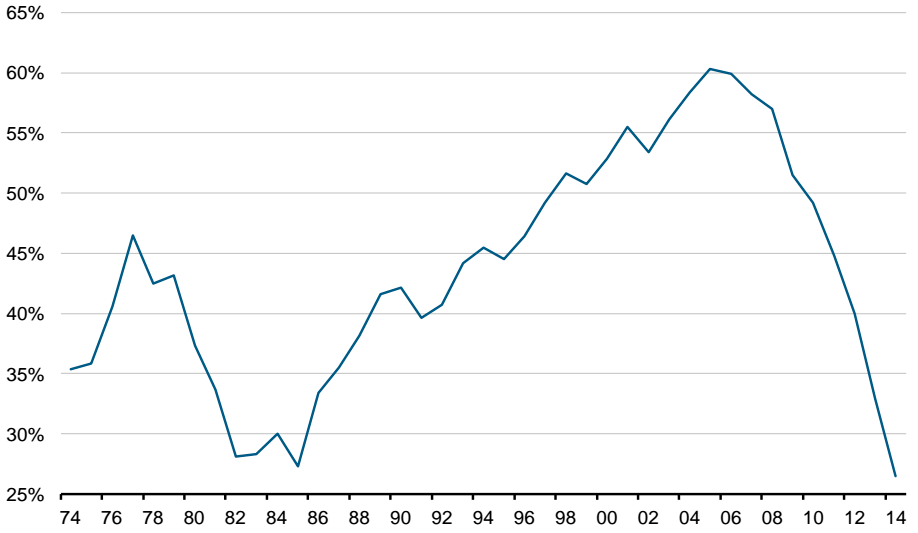

It’s the latest battleground in a series of contests in the mid-2010s that have generally brought setbacks to the populist left. A Lasso victory on Sunday could add pressure to Venezuela’s increasingly autocratic government, and boost conservative opposition hopes in Chile’s elections later this year and in Bolivia’s in 2019.

Former bankers do not typically make great politicians, but Lasso narrowly forced a runoff by holding former vice president Lenín Moreno to just below 40% in first round on February 19.

That gives Lasso a head-on opportunity to face Moreno without dispersing multiple opposition forces within Ecuador. Third-placed candidate Cynthia Viteri, a former legislator and a social conservative, has endorsed Lasso. Fourth-placed Paco Moncayo, a leftist who served as Quito mayor from 2000 to 2009, has refused to endorse either of the two finalists — a snub to Correa and Moreno.

Viteri’s support and Moncayo’s ambivalence have both boosted Lasso’s runoff chances, though it may still not be enough — Lasso finished more than 11% behind Moreno in the first round. Indeed, most polls give Moreno a slight edge over Lasso, a longtime president of the Bank of Guayaquil whose political experience is negligible — he served briefly as ‘superminister for finance’ in 1999 during the scandal-plagued administration of Jamil Mahuad, sentenced to a 12-year prison sentence in 2014 for embezzlement. In 2012, Lasso formed a new opposition party, Creando Oportunidades (CREO, Creating Opportunities) to back his presidential ambitions in 2013. Lasso finished a humiliating second place (with just 22.7% of the vote) to Correa, who won a first-round victory with 57.2% support. But that race put Lasso in position to consolidate support as the chief opposition candidate this year. Continue reading As Lasso rises, Ecuador could be next leftist LatAm domino to fall