Photo credit to Bill Majoros.

U.S. foreign policy isn’t just the stuff of policy papers, talks at Washington think tanks, strategy positions in Foggy Bottom and the work of establishing economic ties, trade links and military alliances drawn up in the bowels of the Pentagon.

To borrow a concept from Joseph Nye, that’s all ‘hard’ foreign policy.

But there’s also a ‘soft’ foreign policy, and it’s the kind of thing that can equally affect foreign relations, often in explosive and unpredictable ways. Officials in tiny Denmark never anticipated their country would alienate the entire Muslim world when the Jyllands-Posten newspaper printed several disparaging images of the prophet Mohammed in 2005. Nor did French officials have a role in the publication, week after week for decades, of the Charlie Hebdo satire magazine, but last week’s horrific murders in Paris could become the focal point of French domestic and foreign policy discussion for weeks, months or even years to come.

So, too, the latest manufactured scandal on the American political scene, a decision by Duke University, a private university in Durham, North Carolina, to allow its chapel to be used for a weekly call to prayer for Muslim students. Under pressure from Christian groups, conservative activists and preachers like Franklin Graham, and in the face of several threats, according to Duke officials, the administration backed off today. Instead of using Duke Chapel, Muslim students will sound the prayer call from the quadrangle in front of the chapel, instead of from the chapel’s bell tower.

It just so happens that I have some interest in this story because I am, myself, a graduate of Duke University. For whatever reason, Duke has found itself at the center of several controversies in recent years, from a 2001 incendiary advertisement regarding slavery reparations that we ran in our days in charge of the student newspaper, The Chronicle, to more serious issues, including prosecutorial abuse in the now-famous 2006 lacrosse rape case. The school’s most recent headlines involved a certain porn star amid its undergraduate student body. But I’m proud to say that Duke is at the center of this latest controversy, in particular, because universities should be precisely the place where students and free thinkers smash against the conventional boundaries of society, ideology and every other sacred cow.

As David Graham (another Dukie and Chronicle alum) writes for The Atlantic, the chapel issue is really less about religion than about the type of society that the United States wants to be in the 21st century, and he quotes Omid Safi, the director of the Duke Islamic Studies Center, who really nails this concept:

“At the end of the day, this is not an Islam conversation,” Safi told me. “It’s an America conversation. It’s a ‘who do we want to be and how do we want to arrange and accommodate diversity?’ conversation. Are we a zero-sum society? Are you less of who you are if I am who I am?”

But we can’t really have a grand debate about freedom of religion or freedom of expression in the context of a private university. Government played no role in either enabling or restricting anyone’s religious rights on Duke’s campus. But that doesn’t mean the discussion won’t inform future US attitudes and the world’s impression of US attitudes toward the freedom of religious expression.

Just as in Denmark in 2006 and in France today, the catalyst of the debate comes not over laws and regulations so much as the cultural values, assumptions and norms that often, ultimately, inform laws, be it increasingly tougher Danish restrictions on immigration or the 2010 French law that prohibits public face coverings, such as the burqa that many Muslim women wear. Continue reading The Duke Chapel brouhaha and US ‘soft’ foreign policy →

![]()

![]()

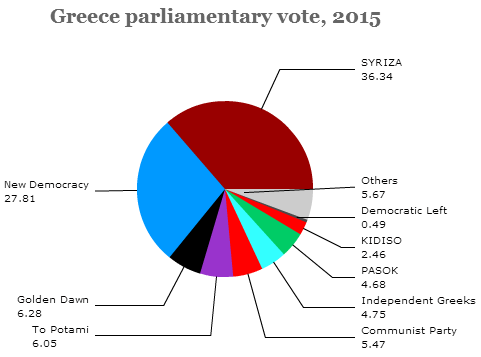

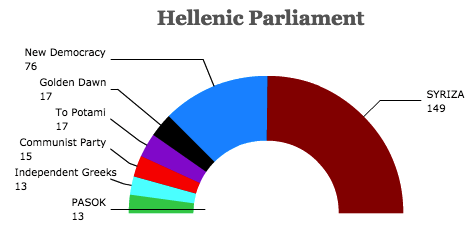

Despite a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for SYRIZA, which significantly outpolled New Democracy, the party fell just short of an outright majority in Greece’s unicameral Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Earlier, today, however, Tsipras

Despite a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for SYRIZA, which significantly outpolled New Democracy, the party fell just short of an outright majority in Greece’s unicameral Hellenic Parliament (Βουλή των Ελλήνων). Earlier, today, however, Tsipras