After weeks of tension, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu sacked justice minister Tzipi Livni and finance minister Yair Lapid on Tuesday, accusing them of trying to lead a ‘putsch’ against him, and the Knesset (הכנסת), Israel’s unicameral parliament, has now voted to dissolve itself in advance of snap elections in early 2015.![]()

Just two years and two months after Israel’s last parliamentary election, Israel is set to go to the polls on March 17, two years sooner than the current parliamentary term ends. Despite Netanyahu’s bravado in triggering early elections, neither he nor Lapid nor Livni are assured of increasing their share of the vote.

While Netanyahu remains the favorite to return as prime minister as the head of his center-right Likud (הַלִּכּוּד), he will be vying to win a fourth term leading government after two of the toughest years of his political career. Though the election is likely to focus, increasingly, on domestic issues, it follows this summer’s ‘Operation Protective Edge’ against Hamas in the occupied Gaza strip that lessened global support for Israel. It also follows Arab-Jewish violence in Jerusalem in recent weeks, and after Sweden formally recognized Palestine’s sovereignty in October (as the French parliament voted on the issue earlier this week).

* * * * *

RELATED: Twelve lessons to draw from Netanyahu’s new Israeli cabinet government [March 2013]

* * * * *

Nevertheless, unless terrorism or religious violence increases, the Palestinian question will invariably fade from the agenda of the country’s leading politicians — for at least the next four months.

Accordingly, the election will be a referendum on Netanyahu’s leadership over the past two years, including the management of his coalition, the struggle of Israel’s middle class, and global matters like his handling of the Gaza war and testy relations with the United States and the Obama administration. Critics from both the left and right will target Netanyahu during the 2015 campaign. Moreover, if Netanyahu falls short next March, his position within Likud is even more tenuous after he wasted precious political capital attempting (and failing) to block former Knesset speaker Reuven Rivlin’s presidential candidacy.

With allies like these, who needs enemies?

The unwieldy coalition Netanyahu formed in 2013 has been increasingly unstable since the end of the military action in Gaza earlier this year. The causes lie not only among moderate critics to Netanyahu’s left like Livni and Lapid, but among conservative critics to his right, including his one-time chief of staff, economy minister Naftali Bennett and his nationalist foreign minister, Avigdor Lieberman. During the Gaza conflict, Netanyahu nearly fired Bennett after his strident criticism that Israel’s military action wasn’t going far enough.

It’s no understatement to say that, since March 2013, Netanyahu’s wiliest enemies were part of his government, not sitting in the opposition benches.

Livni, a former foreign minister and the chief opposition leader to Netanyahu between 2009 and 2012, opposed the government’s most recent attempt to pass Israel’s controversial ‘nationality’ law, which would have defined Israel as a Jewish state. Livni worries that such a law would contradict Israel’s fundamentally democratic nature by emphasizing Israel’s ‘Jewishness’ over its underlying liberal democracy. Other secular critics allege that the law will endanger the rights of Israel’s Arab minorities and undermine its increasingly rocky relationships with the United States and other European democracies. Even Israel’s new president, Rivlin, who comes from Netanyahu’s own Likud, harshly condemned the bill in an atypical speech last week.

Livni (pictured above) todays leads the liberal Hatnuah (התנועה, ‘The Movement’), a party she founded in late 2012. She agreed to join Netanyahu’s coalition in after the previous elections in exchange for a guarantee that she, as justice minister, would lead any peace negotiations between Israel and Palestinians (which, despite US secretary of state John Kerry’s best efforts, disintegrated earlier this year).

Following the Knesset’s decision to dissolve itself, Livni lashed out at Netanyahu in harsh terms:

“The truth behind the hysterical talk yesterday is that we have a prime minister who is afraid,” she told the Hatnua[h] Knesset faction. “A prime minister who is afraid of his ministers is even more afraid of the outside world, and his way of dealing with his fears is through his speeches. The problem is that in facing the real threats against Israel, the regional threats, speeches don’t help.

Lapid, a telegenic former television news anchor, was the surprise victor of the 2013 elections, when his own newly established party Yesh Atid (יש עתיד, ‘There is a Future’) won the second-largest bloc of Knesset seats after emphasizing the high cost of living, social welfare concerns and other economic issues.

Like Livni, Lapid agreed to join Netanyahu’s cabinet, but as finance minister. In that role, Lapid (pictured above) has been responsible for budget cuts to bring Israel’s growing budget deficit into line. That has been predictably unpopular. In recent months, however, Lapid has championed a tax break to exempt first-time homeowners from the VAT payable on newly purchased homes. Netanyahu and deficit hawks have scoffed at the proposal, arguing that it would increase Israel’s budget deficit.

One of Lapid’s chief campaign pledges in the previous election was to end a longstanding exemption from military service in the Israel Defense Forces for ultraorthodox yeshiva seminary students. The issue forced Israel’s two haredim parties (which together hold 20 seats in Knesset) out of Netanyahu’s current government. A law gradually ending the military exemptions narrowly passed the Knesset earlier this year, marking one of the coalition’s major accomplishments and a key legislative accomplishment for Lapid.

Like Livni, Lapid slammed Netanyahu’s decision for early elections, attacking the cost of 2 billion shekels ($500 million), and calling instead for a more robust social welfare component to Israel’s budget. Both Lapid and Livni strongly opposed the government’s steps toward supporting new settlements in the West Bank.

Lieberman (pictured above with Kerry), the leader of the more nationalist Yisrael Beiteinu (ישראל ביתנו, ‘Israel is Our Home’) is not expected to merge his party formally with Likud in 2015 (as he did in 2013). Since his acquittal on fraud and breach of public trust charges last November, Lieberman has returned as foreign minister, however, and he remains Netanyahu’s most reliable ally. Like many Likudniks, however, that could change if Netanyahu, whose approval ratings have dropped from the high 70s at the end of the summer to around 40% today, stumbles in the upcoming elections.

Bennett and Kahlon rising?

Polls today show that the only party in Netanyahu’s coalition set to make gains will be Bennett’s Bayit Yehudi (הבית היהודי, ‘The Jewish Home’), which falls to Likud’s right. Bennett, once Netanyahu’s right-hand man, had a falling out with Netanyahu in the late 2000s. Bennett, a successful tech businessman and a former spokesman for a pro-settlement group, returned to frontline politics just in time for the 2013 election as the leader of Bayit Yehudi, and he nearly quadrupled the party’s presence in the Knesset. As economy minister, he has been notably outspoken as a conservative thorn in Netanyahu’s side on all matters, especially on settlements and issues of national defense.

Photo credit to Haaretz / Shiran Granot.

Photo credit to Haaretz / Shiran Granot.

Underlying the ‘none of the above’ mood in the country, one of the most promising candidates today is former Likud minster Moshe Kahlon, the son of Libyan immigrants. Kahlon served as communications minister from 2009 to 2013 and oversaw the deregulation of Israel’s mobile phone and telecommunications industry. In 2011, he also became minister of welfare and social services. He didn’t run for reelection in the 2013 elections, however, as rumors swirled that he had grown disenchanted with Netanyahu’s economic policies and his approach to diplomacy.

Kahlon, who may be to the 2015 elections what Lapid was to the 2013 elections, has promised to form a new party, and polls indicate that he could win between seven and 12 seats in the Knesset. By positioning himself in the center of Israeli politics, he could appeal to supporters of both Lapid and Livni and to other disenchanted voters. As a former Likudnik, his center-right credentials make him a potent threat to Netanyahu, especially as Bennett and Lieberman have forced Netanyahu further to the right since the 2013 elections.

Though it’s too early to say that Kahlon will triumph, there’s already discussion that former interior and education minister Gideon Sa’ar, who left the Knesset earlier this month after clashing with Netanyahu (including over the Rivlin presidency), might join forces with Kahlon.

What to expect after March?

There’s no doubt that Israel’s next government will also be a delicately balanced coalition government.

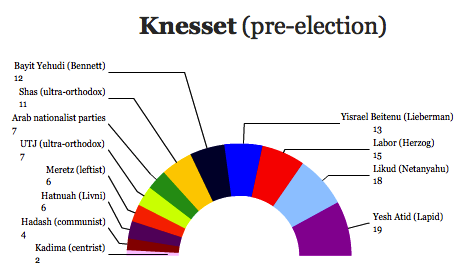

In the last three decades, the relatively stable two-party system consisting of Likud and the center-left Labor Party (מפלגת העבודה הישראלית) has fragmented to the point that no single party holds more than 19 seats in the 120-member Knesset.

A recent change in Israel’s election law raised the threshold for winning seats from 2% to 3.25%, a move that will likely doom the Kadima (קדימה, ‘Forward’), the centrist party formed in 2005 by the late Ariel Sharon, who died earlier this year.

It will almost certainly force Israel’s three Arab parties to join forces, lest they compete separately and fail to reach the 3.25% hurdle. Though turnout among Arab Israeli citizens (separate from Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza who have no voting rights in Israeli elections) has declined in successive elections, the nationality law has enraged Israeli Arabs, who believe that it’s a way of codifying their status as second-class citizens. If so, massive Arab turnout could maximize a unified Arab presence in the Knesset. That, in turn, could boost the chances of a leftist/secular coalition.

For now, while Netanyahu’s popularity seems precarious, no one else has emerged to challenge his hegemony in Israeli politics. That could change over the course of the campaign, with such a large target on Netanyahu, which explains why Likud pushed for a vote as soon as possible. (Elections can only take place at least three months after the Knesset’s dissolution).

On the basis of current polling surveys, Likud would slightly increase its share of seats in the Knesset, which would give Netanyahu the strength to form a more right-wing coalition than the 2013-15 government, which would include Lieberman’s Yisrael Beitenu, Bennett’s Bayit Yehudi and the two orthodox parties, Shas (ש״ס) and United Torah Judaism (יהדות התורה המאוחדת). But if Likud doesn’t emerge as the largest of the right-wing parties, Rivlin might take pleasure in denying Netanyahu the first chance at forming a new government.

Photo credit to Miriam Alster/Flash90.

Photo credit to Miriam Alster/Flash90.

Although Labor dumped its former leader Shelly Yanukovich last November, its new leader Isaac Herzog (pictured above) hasn’t shown any signs of particularly exciting the Israeli electorate, fully 15 years after Labor last held power under prime minister Ehud Barak (who ended his career as Netanyahu’s defense minister). It’s not inconceivable that, by March, Labor could win enough support to cobble together a coalition that includes Lapid, Livni, the Arab parties, other leftist parties, such as the Zionist leftist Meretz (מרצ, ‘Energy’), and quite possibly, Kahlon’s new group. But it seems like an uphill struggle on the basis of current polling and any Labor-led coalition would be as unwieldy as the current five-party coalition. Former president and one-time Netanyahu opponent Shimon Peres, no longer constrained by the formal trappings of a head of state, might also be more critical over the course of the election.