Europe may be a non-issue in the German election campaign, but it’s becoming increasingly clear that Europe will occupy a chief role in the agenda of Germany’s next chancellor, perhaps more so than exclusively German domestic issues.![]()

![]()

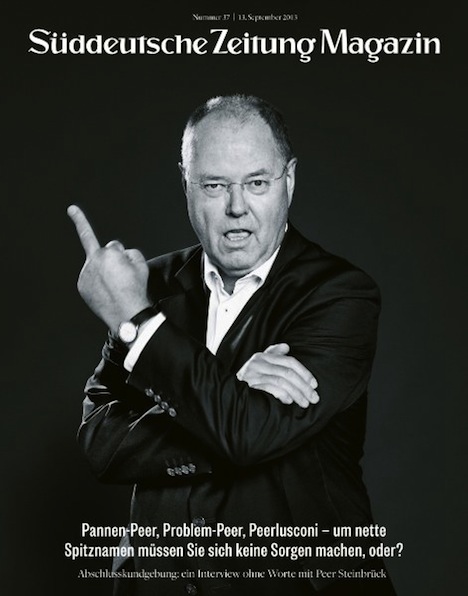

Though center-right chancellor Angela Merkel and center-left challenger Peer Steinbrück are both stridently pro-Europe, it’s an open question how to next German government should deal with the poster-child of the European financial crisis — Greece. To understand Germany’s options requires an understanding of the underlying Greek politics — and how a Greek political crisis could plunge the entire eurozone back into panic mode.

Even as Germany and the eurozone as a whole pulls out of the worst of the most recent recession, Greece continues to struggle with economic contraction. The economy is set to shrink by between 4.5% to 5% this year, the unemployment rate is a staggering 27.6%, and this follows five consecutive years of recession capped off by a 7.1% contraction in 2011 and 6.4% contraction last year. Greece remains trapped in a grueling internal devaluation where the private sector is being forced to accept leaner wages to make exports more competitive and the public sector is being forcibly downsized by the terms of the bailout programs agreed to by the ‘troika’ of the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund. Greece today is not a fun place to live, and Greek voters are angry at Germany in particular for forcing so many Greeks into poverty and joblessness while doing little in terms of fiscal or monetary policy to boost the country’s medium-term growth prospects.

But German voters have their own narrative — while they’re still generally supportive of ever close union within Europe, they’re nonetheless wary of the European Union becoming a transfer union where wealth from German productivity flows to Greek profligacy. That underlies the collective angst within the entire Germany political community late last month when Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany’s finance minister, indicated that Greece would require a third bailout — perhaps up to €11 billion, which is still a fraction of what the troika has already lent to Greece. (For the record, Portugal’s government is also likely to require a second bailout of its own early next summer.)

Back in Greece, that means a politically radioactive set of negotiations at a time when Greece’s government is reeling. A coalition between the two once-dominant parties since the return of Greek democracy in 1974, the center-right New Democracy (Νέα Δημοκρατία) and the center-left PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement – Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα) holds just a cumulative 155 seats, giving it the barest of majorities in Greece’s 300-member Hellenic Parliament. After the disastrous shutdown of Greece’s public television station ERT in June, the anti-austerity Democratic Left (Δημοκρατική Αριστερά) left the governing coalition — its leader Fotis Kouvelis previously agreed to join the coalition after Greek’s June 2012 elections in order to provide more stability for the country.

Snap elections seem likely in any event sometime next year. If elections were held today, SYRIZA (the Coalition of the Radical Left — Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς) seems likeliest to win them, according to a recent poll, making the young, massively anti-austerity opposition leader Alexis Tsipras Greece’s radical new prime minister. The Sept. 11 Public Issue poll showed SYRIZA moving into first place with 29%, New Democracy with 28%, and the far-right, neo-fascist Golden Dawn (Χρυσή Αυγή) would win 13%. PASOK, meanwhile, would fall to just 7%, the Greek Communist Party (KKE) would win 6.5%, the right-wing, anti-bailout Independent Greeks would win 5.5%, and the Democratic Left would win just 2.5%, less than the 3% threshold for entering parliament.

SYRIZA has essentially consolidated much of the support of the anti-austerity left, so it’s puzzling how PASOK still attracts even 7% support, given that it’s subjugated itself almost completely to prime minister Antonis Samaras’s agenda. But Golden Dawn’s support is rising, and it’s likely to pull support from increasingly frustrated right-wing voters that once supported New Democracy, suggesting that if economic conditions keep deteriorating, Golden Dawn could draw even more support to a largely xenophobic, nationalist agenda.

If those numbers held up in a new Greek election, Merkel and her colleagues in Paris, Brussels and other European capitals, would probably regard it as a disaster for Europe. Continue reading What kind of a deal can Greece expect after the German elections?