Fifty-four years after Amma Magnani starred in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s classic Mamma Roma, redefining feminism for Romans and Italians alike, the Eternal City is getting what centuries of imperial and papal rule never allowed — a woman in charge.![]()

![]()

Say what you will about her, unlike Magnani and unlike the founder of her party, Beppe Grillo, Virginia Raggi is no comedian.

For a movement that has sometimes suffered by the fact that its most prominent leader and founder is Grillo, a comic-turned-politician, it now enters a phase where it will be judged by governance, and not just politics. The protest Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) emerged in Italian politics in the 2013 parliamentary elections as an anti-austerity and anti-eurozone force, drawing votes from the remnants of Silvio Berlusconi’s center-right coalition as well as disenchanted leftist voters.

The Five Star Movement controls 91 seats in the 630-member lower house of Italy’s parliament, the Camera dei Deputati (Chamber of Deputies), where its role has chiefly been to throw sand at both the Italian right and the dominant Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party) of prime minister Matteo Renzi.

That will all change after Sunday, when Rome’s (and Turin’s) voters elected two women affiliated with the Five Star Movement, giving it the opportunity to mature into a new role — a functional party of municipal government.

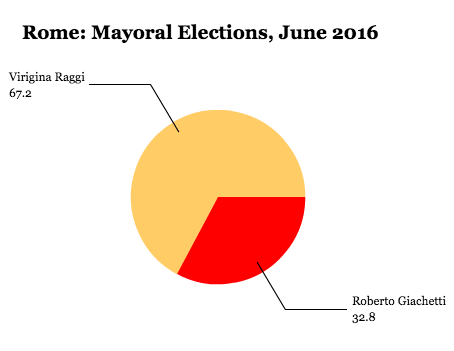

The 32-year-old Chiara Appendino has won a runoff to become the next mayor of the northern industrial city of Turin, but the real prize is Rome, where Virginia Raggi has easily won a runoff against Democratic Party challenger Roberto Giachetti to become the Italian capital’s first female mayor. It is also, by far, the most high-profile electoral success of the Five Star Movement to date.

Rome, home to nearly 2.9 million people, is the European Union’s fourth-largest city after London, Berlin and Madrid. But successive governments have left voters angry, just about everything — roads are worn, public transportation chugs along slowly and trash often goes uncollected. Residents have been dreaming for decades of a third line for the city’s burdened two-line subway system, but construction has stalled under each of the last two administrations.

The last elected mayor, Ignazio Marino, a novice in Italian politics and a former transplant surgeon, resigned in disgrace late last year after just two years in office, implicated in an expense scandal in which Marino apparently charged around €20,000 for personal dinners with friends.

Marino’s personal scandal followed the even wider Mafia Capitale scandal, which saw politicians misappropriate public funds (including funding set aside for the education of marginalized Roma children) to organized crime units in both Rome and the surrounding Lazio region. Moreover, by the time Marino finally resigned, no one — not even Renzi, let alone everyday Romans — seemed to have much faith in Marino’s ability to run the city. The Genoa-born Marino came to politics only in 2006 with his election to Italy’s Senato (Senate).

Marino managed to win election in June 2013 only because of the massive unpopularity of his predecessor, Gianni Alemanno, a controversial figure and Berlusconi ally with former ties to the neofascist right who seemed more concerned with stirring up his national profile than the mundane matters of day-to-day governance in Rome. Continue reading Rome elects Raggi, Five Star Movement candidate, as first female mayor