Voting began earlier today to select the new Italian president among the electoral college that’s gathered for that express purpose, and it’s left Italian politics once again in disarray, this time by revealing a split among the centrosinistra led by an incredibly powerless Pier Luigi Bersani after two ballots failed to elect a successor to Giorgio Napolitano who, at age 86, is not running for reelection for another seven-year term.

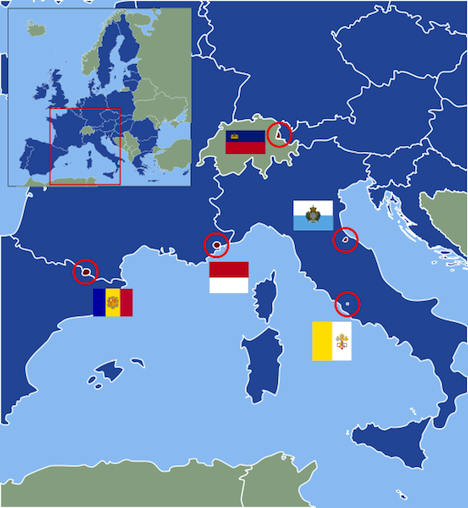

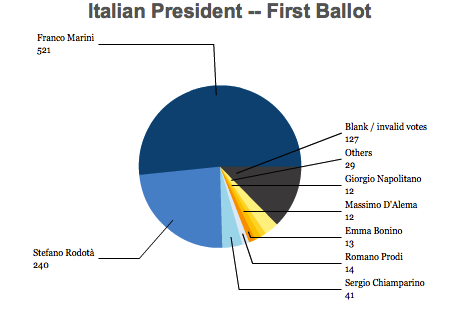

The Italian president, whose role remains essentially ceremonial, is not elected directly, but through an electoral college that includes the members of both houses of Italy’s parliament, plus a special group of electors that includes three members for each region (except for the Valle d’Aosta, which has just one) that total 1,007 voters. A president can be elected on the first three ballots only with a two-thirds majority; on the fourth ballot, a simple majority can elect the president, as happened in 2008 with the election of Napolitano.

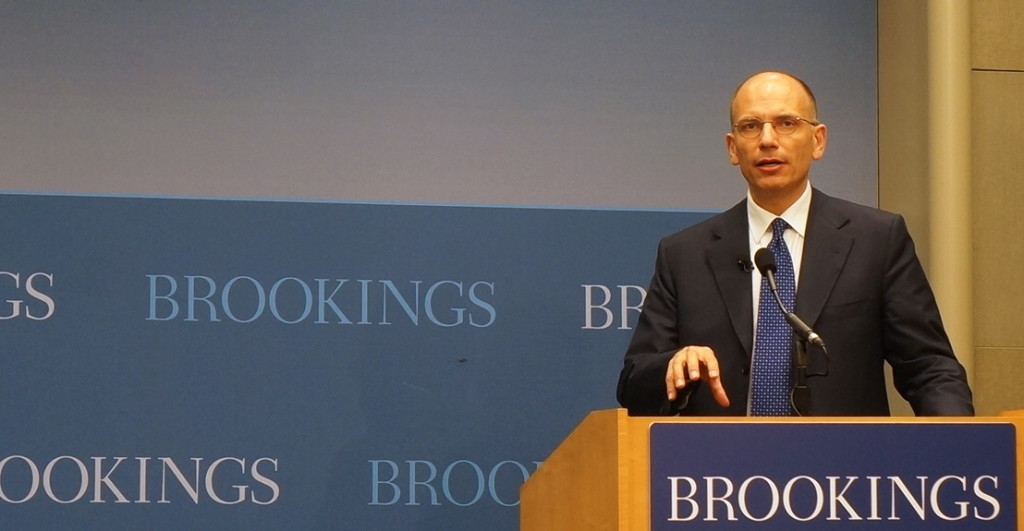

At the end of last month, I highlighted some of the potential technocratic prime ministers that outgoing president Giorgio Napolitano might appoint. In the interim, he’s chosen to continue talks and keep prime minister Mario Monti in place to tend to day-to-day government affairs while the presidential vote proceeds.

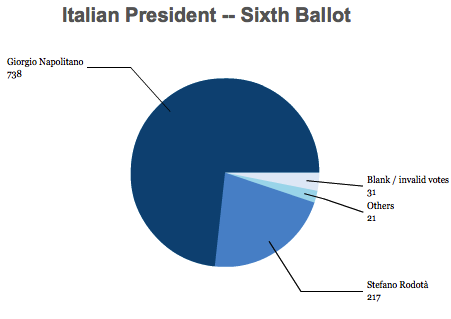

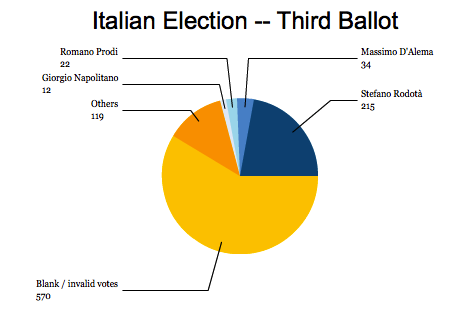

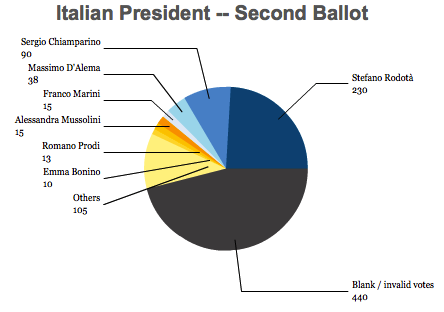

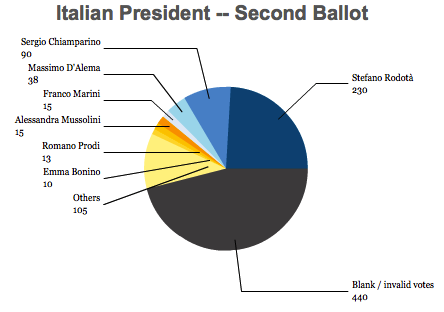

One of those potential consensus candidates was Stefano Rodotà (pictured above), who finished tops in the second ballot just held by the Italian presidential electoral college this afternoon with 230 votes to just 90 for former Turin mayor Sergio Chiamparino, 38 for former prime minister and foreign minster Massimo D’Alema and a bare 15 for the former first ballot leader Franco Marini, who originally had not only Bersani’s support, but the support of Silvio Berlusconi as well, leading to a howl of ‘corrupt bargain’ accusations.

The result is a disaster for Bersani — The Economist blasted it as the failure of an ‘inciucio,’ a Napolitano word meaning ‘stitch-up,’ and Alberto Nardelli has brutally written that Bersani’s deal with Berlusconi reveals that he’s putting his own career over the interests of Italy:

Bersani (who says he doesn’t want to form a government with Berlusconi) is happy to deal behind closed doors, and in attempting an agreement on the presidency, the PD leader is hoping that the PDL will then not obstruct the formation of a government. The goal isn’t a ‘government of change’, it’s landing the job – the mask has slipped.

This is (Italian) politics at its worse – career ahead of country and leading via back room deals in the style of country fairs where livestock is exchanged. And many still wonder why Beppe Grillo is so popular.

How Bersani blew it

Marini’s collapse was a predictable blunder, and it goes to the heart of why Italian politics is in the dysfunction state that it’s in.

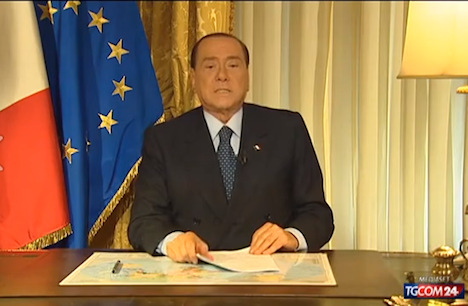

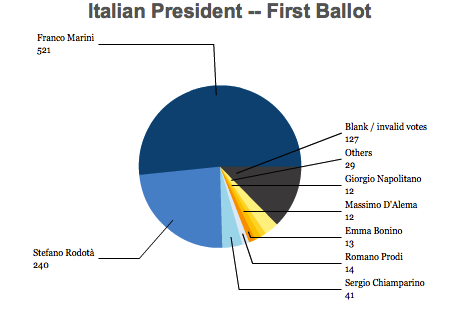

Bersani, who leads not only the center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), but the broader center-left coalition that also contains the more socialist Sinistra Ecologia Libertà (SEL, Left Ecology Freedom), led by Nichi Vendola, agreed to support Marini on the first ballot, who also received the support of the centrodestra coalition dominated by Silvio Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom) and Monti’s centrist, reformist allies.

The center-left in Italy contains essentially two strands — those who came out of the world dominated by Democrazia Cristiana (DC, Christian Democracy) that controlled Italian government in the post-war period through 1993, and those who came out of the tradition of the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI, Italian Communist Party), consistently in opposition to the hegemonic and increasingly corruption Christian Democracy (and their various allies), who were mostly wiped out of office after a series of scandals in 1992 and 1993. Napolitano, for instances, comes from the Communist background.

But Marini, age 80, comes not only from the Christian Democratic world, he was a member of Democrazia Cristiana since 1950, the leader of the Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Lavoratori (CISL, Italian Confederation of Trade Unions), the trade union arm of Christian Democracy in the 1980s, and minister of labour to Giulio Andreotti, who was thrice prime minister between the 1970s and the 1990s and is synonymous with the Catholic right wing of Christian Democracy. Marini was the president of the Senato from 2006 to 2008, however, when Romano Prodi governed Italy, but he lost his senatorial seat in February’s elections. As Florence mayor Matteo Renzi said, Marini comes from ‘the last century’ of Italian politics, and his failure to win reelection makes him a poor choice to represent vital Italian democracy in 2013.

All of which would have made Marini a poor choice for the presidency, but Berlusconi’s endorsement made Marini all but toxic. Bersani had previously refused to make any deal with Berlusconi over a governing coalition (despite Berlusconi’s repeated offers for a ‘grand coalition’). So his volte face immediately caused alarm even within his own ranks. That includes not only much of the SEL, but significant portions of Bersani’s own Democratic Party, including Renzi, all of whom refused to support Marini. Theoretically, the centrosinitra and centrodestra could have pooled enough votes to win on the first ballot, but Marini’s 521 first-ballot supporters were just barely a majority, opening a wide schism in the centrosinistra, and strengthening Renzi, a popular, young mayor who, at age 37, who lost last November’s primary contest to Bersani to led the centrosinistra in the February election.

Rodotà and the politics of change

Renzi, who’s called for a new generation of leadership on both Italy’s left and right, is the most popular politician in the country. If a second election is called, and the centrosinistra is dumb enough to stick with Bersani as its leader, it will lose. But if the centrosinistra chooses Renzi to lead it into the next election, it will probably win in a landslide, because Renzi’s message blends the best of both the center-left and that of the Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement), a diverse, largely anti-austerity protest group led by blogger, comedian and popular activist Beppe Grillo into power as the third force of Italian politics on a platform of more transparency and better governance, among other priorities.

The deal between Bersani and Berlusconi personifies the kind of old-school back-room dealing that Renzi has decried and that powered the Five Star Movement into the spotlight. So the Marini candidacy gives both Renzi and the Five Star Movement even more evidence that the barons of the center-left and the center-right still don’t understand the way that Italian politics changed after February’s election.

Rodotà, who placed second on the first ballot with 240 votes, is the candidate of the Five Star Movement, which held an online ballot to determine its preferred candidate for the presidency. Although its top two choices declined to stand for the presidency, its third-place candidate was Rodotà. Though Rodotà, too, is just shy of 80 years old, he’s a former deputy who stood against the Christian Democratic-dominated oligarchy in the 1980s, and he was one of the first leaders of the Democratic Party of the Left that emerged as the more moderate wing of the old Italian Communists and is a predecessor of the Democratic Party that Bersani today leads. A legal scholar based in Rome, he’s spent much of the past decade as an activist for electronic privacy rights in Italy and the European Union.

What’s most amazing about all of this mess is that after the next ballot, which will be held tomorrow, the united centrosinistra will likely be able to push through their own candidate on the fourth ballot, which will be held either tomorrow or Saturday at the latest — they’ll be just a handful of votes short of a simple majority. So Bersani could have probably just allowed a free vote on the first three ballots, then pushed for the consensus candidate of the center-left acceptable to Vendola and the SEL, on the one hand, and Renzi, on the other. Instead, Bersani has weakened what’s already an amazingly weak position as the Democratic Party leader by attempting to broker a deal with Berlusconi to install an unpopular remnant of Italy’s First Republic in the presidency. It seems incredibly difficult to see how Bersani will remain the Democratic Party leader for much longer.

What comes next?

Chiamparino, at age 64, (pictured above) is a popular leftist from the old Communist tradition who’s a popular former mayor of Turin, gained votes between the first and second ballots, and he could well become the consensus candidate of the centrosinistra in advance of the third and the key fourth ballot, both of which will be held tomorrow — Renzi has indicated that Chiamparino is his first choice.

Other candidates likely include former prime minister Giuliano Amato, but he’s seen as a throwback to the First Republic as well. D’Alema and Prodi remain potential candidates, though both are seen as insiders and electoral losers, though Prodi perhaps has a better shot as a former European commissioner and a two-time former prime minister who led the center-left to victories in 1996 and in 2006.

I still think that Emma Bonino, a longtime human rights champion and good-government Radical Party senator since the 1980s, would make a wonderful choice for the center-left because she has the kind of appeal that transcends ideology, which makes her very much like Napolitano, the outgoing president. She would also be a historic choice as the first woman to become Italy’s head of state.

Another option is for the left to simply join forces with the Five Star Movement and back Rodotà, of course.

We’ll know a lot more in the hours to come.

![]()

![]()