Although relatively more attention has been on Italy’s general election and its aftermath and on Roberto Maroni’s victory in the Lombardy regional elections, Nicola Zingaretti’s victory as the next regional president of Lazio has launched the career of a new face of the next generation of Italy’s political leadership while delivering a stinging defeat to one of Italy’s most prominent far-right figures. ![]()

![]()

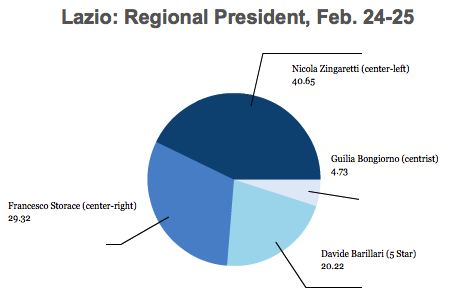

Zingaretti (pictured above), the candidate of the center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), won a whopping victory over Lazio’s former regional president Francesco Storace, leader of La Destra (The Right), a nationalist conservative party in Italy, Davide Barilliari, the candidate of the Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) and Giluia Bongiorno, who led a centrist coalition in the election.

The result leaves the center-left in control of 28 seats in Lazio’s regional parliament, with 13 for the center-right, seven for the Five Star Movement and just two for Bongiorno’s centrists.

Zingaretti, elected to the European Parliament in 2004 and thereafter elected as president of the province of Rome in 2008, is the latest center-left star to emerge out of Roman politics, and he could well use the Lazio presidency as a springboard into a future in national politics. Former Rome mayor Francesco Rutelli (unsuccessfully) led the center-left in the 2001 general election and subsequently served as prime minister Romano Prodi’s minister of culture and tourism. Rutelli’s successor as Rome mayor, Walter Veltroni, helped found the Democratic Party in Italy, and thereupon led it (again, unsuccessfully) in the 2008 general election.

Zingaretti’s first task will be to restore integrity to regional government in Lazio, Italy’s third-most populous region. The outgoing incumbent, the PdL’s Renata Polverini, resigned early after being implicated in a funding scandal whereby public officials were using government funds for private use. Her predecessor, the center-left Piero Marrazzo, lost reelection after he was blackmailed over a video recording of Marrazzo engaging the services of a transsexual prostitute.

More immediately, however, the strength of Zingaretti’s campaign may well have helped Pier Luigi Bersani’s centrosinistra (center-left) coalition win victory in the senatorial contest in Lazio — Bersani’s coalition won just 32.3% against former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s centrodestra (center-right) coalition, which won 28.8%, a much smaller margin of victory than Zingaretti posted over Storace.

The landslide defeat is a setback for Storace, president of Lazio from 2000 to 2005, and one of the most well-known members of Italy’s nationalist right.

But it’s also a setback for Italy’s nationalist conservatives after a campaign saw Berlusconi shared some kind words for Italy’s former fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, and whose party, the Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom), includes Mussolini’s granddaughter, Alessandra Mussolini, a former Playboy model, was elected to Italy’s upper house, the Senato (Senate) over the weekend.

Storace’s own party, The Right, finished the election with just 0.64% and no seats, even though it was part of Berlusconi’s coalition. That’s in part because Berlusconi’s ally and former defense minister Ignazio La Russa formed a new far-right party in December 2012 called the Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy). La Russa founded the party with Berlusconi’s blessing, and with the immediate intention of joining Berlusconi’s coalition.

La Russa’s new party, in fact, won 1.95% of the vote (three times as much support as Storace’s), and nine seats. Everyone’s marveled at Berlusconi’s feat in pulling within 0.4% of defeating the center-left coalition in the weekend’s election, but just as amazing was his ability to co-opt so much of the far-right’s support by enabling what is less a separate party than a PdL offshoot with a nationalist brand.

Storace’s local and national marginalization, however, is also a setback for his nationalist conservative ally, Gianni Alemanno, the current mayor of Rome. Although he’s a member of Berlusconi’s PdL, he won election as Rome’s mayor on the support of the far right, and his election victory was marked by chants of “Duce! Duce!” by neo-fascist skinheads. Nonetheless, as recently as a few months ago, Alemanno was thought a potential future leader of the PdL, but Berlusconi’s dogged comeback in the 2013 campaign (and his less heralded co-opting of the Italian far right) means that Berlusconi’s successor will more likely be his loyal lieutenant and former justice minister Angelino Alfano.

The election also claimed as one of its victims a former neofascist-turned-centrist, Gianfranco Fini, who had joined forces with former prime minister Mario Monti. A one-time Berlusconi ally, Fini formed a new party, the centrist Futuro e Libertà (Future and Freedom), in 2010 — in alliance with Monti, it won no seats and a paltry 0.46% of the vote. Fini himself, the president of Italy’s Camera dei Deputati (House of Deputies) since 2008, failed to win reelection to Italy’s parliament since his first election in 1983.

Throughout much of the postwar period, the neo-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI, Italian Socialist Movement) remained a steady, if small, presence on the Italian right.

In 1995, however, Fini, the leader of the MSI, formed a new party, the Alleanza Nazionale (National Alliance) as a vehicle to navigate the post-Tangentopoli era of Italian politics. Fini, taking advantage of the seismic realignment of Italian politics and realizing, as did the Italian communists, that the end of the Cold War would augur a less radical era, rechristened the ‘National Alliance’ as a party that would remain stridently nationalist and conservative, but would eschew much of its neo-fascist baggage.

Fini’s National Alliance joined forces with Berlusconi’s center-right forces in 1994 and Fini increasingly moved from the far right towards the center-right mainstream. From 2004 to 2006, he served as Berlusconi’s foreign minister and in 2009, Fini merged the National Alliance fully into Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom), a move he would would come to regret.

In the 2000s, however, as Fini moved from the far right to the Berlusconi right and, thereafter, ever further to the center, a new group of nationalist conservative leaders rose to prominence, including Storace and Alemanno.

But despite quite a bit of handwringing over a potential comeback for fascism in Italy, the weekend’s election marks the clearest losses in two decades for the far right.

One thought on “Zingaretti victory in Lazio caps subdued election for Italy’s far right”