German chancellor Angela Merkel, fresh off a victory at the end of last month in her country’s federal elections, turned this week to a once very-unlikely coalition partner — Germany’s Die Grünen (the Green Party).

When news broke last week that Merkel would hold talks with the Greens, it was easy to blow it off as a formality. After all, everyone assumed after the September 22 elections that Merkel’s center-right Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party) would form another ‘grand coalition’ with the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party).

But throughout the campaign, I listed all of the reasons why a ‘black-green’ coalition made a lot of sense — and those reasons still make as much sense now as they did before the election. Merkel’s decision to phase out nuclear power in 2011 removed the key policy difference that most divided her from the Greens. The leadership and the rank-and-file membership of the Greens is becoming older, wealthier and, in general, more like the CDU electorate. Moreover, its younger members are less radical and more moderate, and don’t have the same antipathy to business as the (pardon the generalization) founding ‘1960s, hippie, flower child’ generation.

With the announcement that the Greens and Merkel’s CDU will explore a second round of talks over a potential coalition, however, everyone seems to be taking seriously the possibility of a ‘black-green’ coalition, which would be unprecedented in national German politics (though the Greens and the CDU joined forces in government recently, to mixed results, in Saarland and Hamburg).

There were always really compelling reasons why another CDU/SPD ‘grand coalition’ makes little sense.

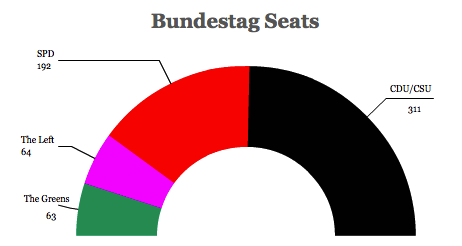

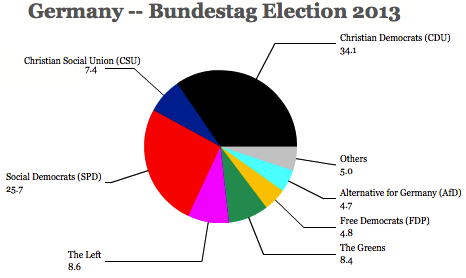

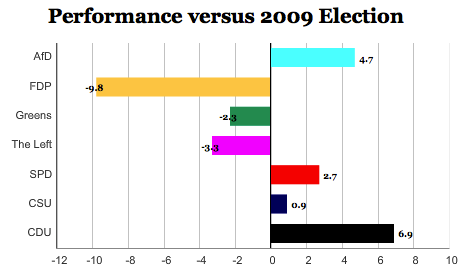

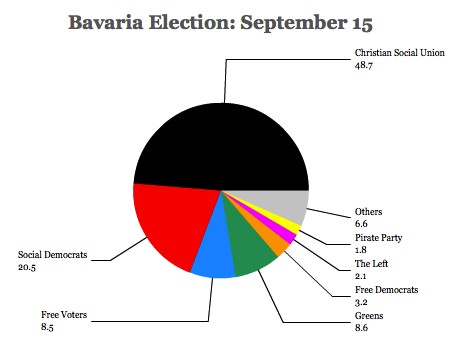

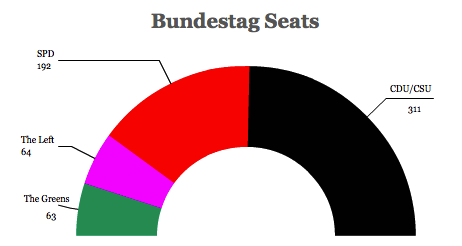

After all, Merkel’s near-landslide victory left her CDU and the more Catholic, conservative, Bavaria-based Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern (CSU, the Christian Social Union) just five seats short of an absolute majority. She doesn’t need the SPD’s 192 seats, she needs five votes. Moreover, the SPD’s collaboration with Merkel won it few votes, neither in Germany’s 2009 federal elections when the grand coalition’s foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier led the party to its worst election result in postwar history nor in the most recent elections when the grand coalition’s finance minister Peer Steinbrück led the SPD to its second-worst result. As such, the SPD is looking to draw a contrast with Merkel over the next hour years, not prop up Merkel’s government as her junior partner.

That means that the SPD will be looking for the first opportunity for snap elections — and it’s not exactly a foregone conclusion that Merkel will lead the CDU/CSU into a fourth consecutive campaign. At first glance, a coalition with the Greens may seem more bold, but it might well be the more cautious option for Merkel. They’ll be less likely to cause problems for Merkel and, with a smaller parliamentary caucus,

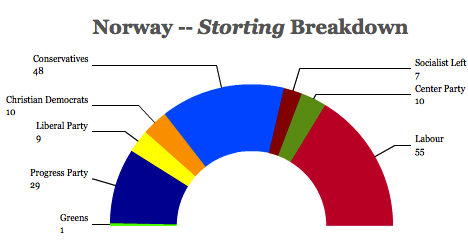

Here’s the breakdown of seats in the lower house of Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag, following the September 22 vote, which will have 630 seats — a ‘grand coalition’ would amount to about four-fifths of the entire Bundestag.

Given that the CDU’s coalition partner between 2009 and 2013, the liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), failed to surpass the 5% electoral threshold and lost all of its seats in the Bundestag in September, there’s only one other party to which Merkel can turn — the Greens.

Though Merkel’s coalition partners might both regret their cooperation (i.e., the SPD and the FDP both notched postwar nadirs in 2009 and 2013, respectively), there’s a strong case that a ‘black-green’ coalition could give the Greens a new identity at the very heart of Germany politics. As a junior partner in Merkel’s third consecutive government, its supporters wouldn’t expect much, so to the extent that the Greens moderate Merkel’s agenda over the next four years (through policies that boost renewable energy or reduce CO2 emissions), their core voters should be fairly satisfied. But the Greens stand to pick up many more centrist voters that might otherwise vote for the SPD or even for the CDU or the FDP.

The Greens ran an undeniably leftist campaign, pledging tax hikes and a 15% wealth tax to boot, along with the oft-ridiculed national ‘Veggie Day,’ and one of its four leaders, Jürgen Trittin, a former environmental minister from 1998 to 2005, faced ridicule over his approval of a pamphlet from 1981 that appeared to call for the legalization of sex between adults and minors. Despite polls that in 2011 showed the Greens winning up to 25% or even 30% of the vote, they finished with just 8.4% of the vote — a swing of 2.3% less than their 2009 total.

Former Green Party leader and foreign minister Joschka Fischer, among others, took the Greens to task for their campaign within 48 hours of the election:

“It looks almost as though the current leadership of the Greens has gotten older but still hasn’t grown up,” Fischer told SPIEGEL following Sunday’s vote. “They followed a strategy that not only failed to win over new voters, but drove away many old ones.” Noting the party’s focus on tax hikes and social spending during the campaign, Fischer said that emphasizing a “leftist course” was a “fatal mistake.”

Former party head Reinhard Bütikofer has likewise not been complimentary of the current Green leadership. “The failure … to engage in a serious debate with Chancellor Merkel regarding … her policies for Europe granted her political hegemony” on the issue, he told SPIEGEL. He also criticized Trittin for being a mouthpiece of the party’s left wing.

Since the election, the Green leadership resigned en masse, and they elected two new leaders, including the centrist rising star Katrin Göring-Eckardt, who had served as one of two chancellor-candidates for the Greens during the election. The Greens, who have long been divided between a more centrist realo (‘realist’) faction and a more radical fundi (‘fundamentalist’) faction, have long elected leaders in pairs (the new leftist Green leader is Anton Hofreiter, who, unlike Trittin, comes from the new generation of Greens parliamentarians).

But the clear exemplar of Greens success is Winfried Kretschmann (pictured above), the first and only minister-president of any of Germany’s 16 states — and in Baden-Württemberg, a wealthy (and relatively conservative) state in Germany’s southwest that’s a hub for commerce and industry. Though Kretschmann came to power in 2011 on a wave of opposition to the Stuttgart 21′ rail development project, Kretschmann is now helping to implement the project after it won nearly 60% support in a subsequent referendum specifically on the project’s future. Kretschmann, who’s firmly within the ‘realo,’ right wing of the Green Party, has won plaudits from business leaders as well, and he’s apparently playing a role in the CDU-Green negotiations.

Severe obstacles remain to a ‘black-green’ coalition. Continue reading Merkel’s coalition talks with Green Party leaders this week seem serious →

![]()