When she was elected in September 2013 as Norway’s new conservative prime minister, one of Erna Solberg’s top priorities was to bring down the value of the Norwegian currency, the krone.![]()

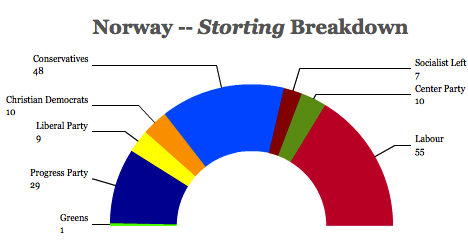

Boosted by its spectacular oil wealth, Norway is today one of the world’s wealthiest countries, so strong that it’s shunned not only eurozone membership but accession to the European Union altogether. Like many other oil-producing countries, however, the sudden drop of oil prices since July from over $100 per barrel to nearly $60 today has adversely affected Norway’s economy. If prices drop even lower, or the $60 level sustains itself through 2015 or beyond, it could endanger Solberg politically, who leads a minority government consisting of her own center-right Høyre (the ‘Right,’ or the Conservative Party) and the more controversial Framskrittspartiet (Progress Party), a more populist, anti-immigrant party that has its roots in the anti-tax movement. The Progress Party’s leader, Siv Jensen, now holds the unenviable task of serving as Norway’s finance minister as oil prices tumble. Solberg ousted the popular two-term prime minister Jens Stoltenberg, who is now NATO secretary-general.

But for a country that was facing inflationary pressure when the rest of Europe continues to battle deflation, the fall in oil prices may bring additional benefits to a country long topping the list of the world’s most expensive places. As of July 2014, Norway still led The Economist‘s ‘Big Mac Index‘ — the price of the iconic McDonald’s sandwich was a whopping 61% higher in Norway than in the United States.

There’s no doubt that a sustained fall in oil prices will harm Norway’s bottom line. It will reduce the revenues available for public spending (already estimated to fall by over $9 billion because of the price drop), and it could easily cause Norwegian GDP growth to fall in 2015 from estimates of 2% or so (still robust compared to the eurozone), thereby causing the country’s relatively low 3.4% jobless rate to climb.

But it’s also caused the krone to fall to a 13-year low, declining to parity with neighboring Sweden’s currency, the krona, for the first time since 2000. As recently as May, one US dollar was worth 5.8 Norwegian kroner. Today, that’s skyrocketed to 7.5 kroner and, as Russia and other oil-exporting countries see their own currencies tanking, investors could push the krone even lower.

Aside from reducing concerns about inflation, the krone‘s fall could provide all kinds of benefits to Norway. For now, Solberg remains incredibly popular with Norwegians. Also for now, Jensen and the government doesn’t seem panicked, though the central bank cut interest rates from 1.5% to 1.25% last week. The current 2015 budget cuts taxes, while holding social welfare spending steady and increasingly spending on the country’s infrastructure. Continue reading Could Norway benefit from the oil price decline?