An astounding scandal in Luxembourg is bringing to light the unfettered abuses of the small country’s secret service and, though its longtime prime minister Jean-Claude Juncker has disclaimed knowledge of the worst abuses, the debate over whether Juncker shares ‘political responsibility’ for the misdeeds has potentially ended Juncker’s remarkable three decades of domestic political dominance — Juncker has announced that his government will resign tomorrow in order to bring forward general elections that were originally expected next spring.

After facing a spectacular loss in a vote of no confidence from both his opponents and coalition allies in Luxembourg’s parliament, the D’Chamber (Chamber of Deputies), Juncker agreed to call early elections as soon as October. Despite speculation that Juncker might resign as prime minister today during his parliamentary testimony over oversight — or lack thereof — of Luxembourg’s secret service and intelligence scandal, he instead challenged his opponents to bring his government down when his coalition partners balked at Juncker’s testimony disclaiming direct responsibility for the abuses, detailed in a parliamentary report presented last Friday. Only after facing certain defeat in a no-confidence vote did Juncker acquiesce to his government’s resignation, and he has not indicated that he hopes to step away from the premiership permanently.

That means Juncker (pictured above), until earlier this year the president of the Eurogroup, may well lead his longtime dominant Chrëschtlech Sozial Vollekspartei (CSV, Christian Social People’s Party) in the next elections, but he will do so from a position of uncharacteristic weakness. An ignominious fall from power could endanger his hopes to succeed current EC president José Manuel Barroso in October 2014 when Barroso’s decade leading the Commission is set to expire.

So what is it that has turned Luxembourg upside down?

As Luxembourgian commentator Jerry Weyer explained earlier this year at his blog (his live updates of today’s parliamentary hearing on Twitter have been incredibly insightful), the scandal focuses on the role of the Service de renseignement de l’Etat luxembourgeois (SREL), the secret service / intelligence agency of Luxembourg. SREL has been up to quite a bit of mischief in Luxembourg, including illegal wiretapping and surveillance of various groups ranging from leftist and green political activists to suspected Islamic terrorists. It has also been alleged to have tried to blackmail homosexual individuals and involved in cover-up operations related to the investigation of the ‘Bommeleeër’ inquiry into a mysterious 1984 terrorist bomb attack in Luxembourg.

The scandal hit headlines late last year when it was revealed that an SREL official illegally recorded a conversation between Juncker and Luxembourg’s grand duke, Henri. That revelation led to further disclosures about SREL abuses of power over the years and to increasingly sharp questions about why Juncker continued to protect the SREL from public inquiry, even when it became clear that he knew about its transgressions (such as, for example, the SREL’s illegal taping of Juncker’s own private conversations). Furthermore, as Juncker has claimed he was unaware of additional abuses, he’s faced tough questions about whether he was too focused on European governance to provide adequate leadership in Luxembourg.

Given that Juncker has been in office since 1995 — five years longer than Grand Duke Henri has served as Luxembourg’s head of state — it has been nearly inconceivable to think about what a post-Juncker Luxembourg might mean, but it’s quickly something that’s become a reality as rivals to Juncker within both the opposition and within his own coalition start to vie for position as Juncker’s position has become increasingly untenable.

Some background is in order — after all, Luxembourg isn’t necessarily the most familiar country to U.S. audiences — or even European audiences who are much more familiar with Juncker’s role with respect to the Eurogroup and the eurozone.

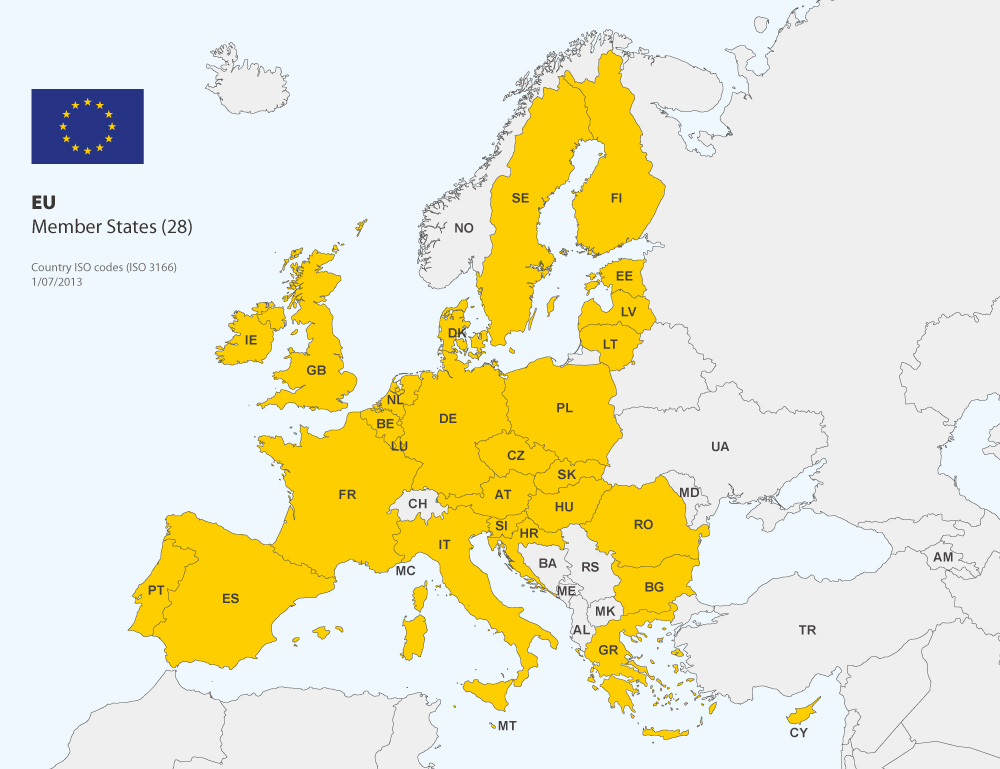

Luxembourg, the tiny grand duchy (the world’s only existing 21st century grand duchy) nudged to the south of Belgium, to the west of Germany and to the northeast of France, is home to just under 550,000 citizens, making it the second-smallest European Union member after Malta in both terms of population and area. Its European pedigree, however, is undisputed — it was one of the six founders of the European Coal and Steel Community in the 1950s that served as the forerunner to the European Union. As a small European country where French and German are both official languages alongside the native Luxembourgish, it has long served an important role smoothing relations between its two neighbors, which have historically served as the twin engines of EU growth and reform.

Consistently pro-European, Luxembourg’s voters approved the ill-fated European constitution in July 2005 with 56% in support of the constitution — and in support of Juncker, who pledged to resign if Luxembourgers opposed the effort — just weeks after two failed referenda in France and the Netherlands.

Juncker’s predecessor and mentor, Jacques Santer, Luxembourg’s prime minister from 1984 to 1995, served as president of the European Commission from 1995 to 1999. Santer played a key role in negotiating the Single European Act of 1986 that fully brought the European single market into effect. Santer, along with every other member of the European Commission, resigned en masse in 1999 over corruption among a handful of European commissioners, though Santer himself was never implicated directly with wrongdoing.

Before assuming the premiership from Santer, Juncker previously served as minister of labour from 1984 to 1989 and as finance minister from 1989 throughout the next two decades. In fact, Juncker continued to serve simultaneously as finance minister, prime minister and Eurogroup president until 2009, when Juncker’s CSV colleague, his longtime justice minister Luc Frieden, was appointed finance minister. In his role as Santer’s finance minister, Juncker became one of the chief architects of the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht and the single currency that Maastricht brought into being. More recently, Juncker was instrumental in formalizing the role of the Eurogroup, the group of finance ministers from each member of the eurozone, and he served as the first Eurogroup president from 2005 until earlier this year, when Dutch finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem was chosen to replace Juncker.

It’s not an exaggeration to argue that no one in European policymaking circles today has more experience and responsibility for the creation, rollout and enactment of the single currency than Juncker, and he played a crucial role in more recent debates over European bailouts for beleaguered Ireland, Greece, Spain and Portugal.

From an initial industrial economy based largely on steel production after World War II, Luxembourg has developed a modern, post-industrial economy that depends in large part on financial services today. With a GDP per capita of nearly $80,000, the tiny nation is by far the richest in the European Union. That hasn’t protected Luxembourg from the broader economic trends that have swept the eurozone — it’s notched only tepid GDP growth since an initial contraction in 2009, though GDP contracted by 1.6% year-over-year in the first quarter of 2013 and unemployment has edged up to nearly 7%.

Its head of state, Grand Duke Henri, is essentially a figurehead, especially after the Luxembourgian parliament clarified that the Grand Duke’s signature is not necessary to enact laws after Henri controversially announced that he would not sign a 2008 law regarding euthanasia.

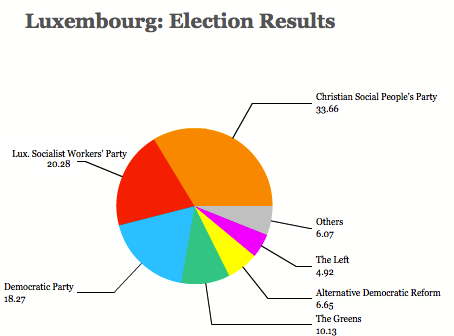

Juncker’s center-right, Christian democratic CSV has long dominated Luxembourgian politics, and all but one of Luxembourg’s prime ministers have come from the CSV since World War II. The CSV controls 26 of the 60 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and during Juncker’s time in office, the CSV has formed governing coalitions with each of its chief rivals, the center-left, social democratic Lëtzebuerger Sozialistesch Arbechterpartei (LSAP, Luxembourg Socialist Workers’ Party) and the center-right, liberal Demokratesch Partei (DP, Democratic Party). While that has perhaps led to an extraordinary amount of continuity within Luxembourg’s government, critics charge that the CSV’s political hegemony has led to a cozy environment where SREL misdeeds and other abuses have gone unpunished.

Though it’s been the CSV’s coalition partner for the past decade, it is the LSAP that has brought about early elections by threatening to bring down the government with a vote of no confidence. Its leader Alex Bodry announced last Friday that the party would push for either Juncker’s resignation or fresh elections.

While the LSAP currently holds 13 seats, the Democratic Party holds nine seats and it’s currently the largest party sitting in opposition, though it has joined the CSV in government between 1999 and 2004. Its president, Xavier Bettel, also the mayor of Luxembourg City, has taken just as critical a line against Juncker, accusing the prime minister of having failed to bring SREL misdeeds to light for public inquiry. Bettel and the Democratic Party are especially well-placed to succeed in the next elections. A poll earlier this spring showed that the young, openly gay Bettel is now more popular than Juncker, though the CSV continues to widely outpace the LSAP and the Democrats, though that could change if Luxembourgian voters want to punish Juncker — for the SREL abuses or more broadly for the sluggish economy.

Three smaller parties also sit in opposition: Luxembourg’s Déi Gréng (Greens) hold seven seats; a nationalist conservative party, the Alternativ Demokratesch Reformpartei (Alternative Democratic Reform Party) holds four seats; and the far-left Déi Lénk (The Left) holds just one seat.

![]()