An infamous campaign poster from the 2007 Swiss election that depicts a flock of white sheep inside Switzerland, with one kicking a black sheep outside — the implication being that the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (SVP, Schweizerische Volkspartei in German; UDC, Union démocratique du centre in French) would tighten immigration policies to keep out migrants and perhaps reverse the trend of greater immigration to Switzerland in recent years. Critics pointed out the nastier racist undertones of the poster.

An infamous campaign poster from the 2007 Swiss election that depicts a flock of white sheep inside Switzerland, with one kicking a black sheep outside — the implication being that the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (SVP, Schweizerische Volkspartei in German; UDC, Union démocratique du centre in French) would tighten immigration policies to keep out migrants and perhaps reverse the trend of greater immigration to Switzerland in recent years. Critics pointed out the nastier racist undertones of the poster.![]()

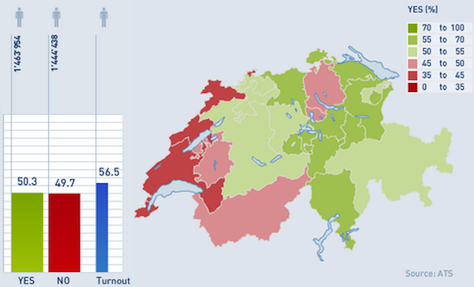

It’s that advertisement that I had in mind today as Swiss voters elected by a narrow 50.3%-to-49.7% margin to adopt an initiative ‘against mass immigration’ that would introduce quotas to Swiss immigration, despite the wishes of the Swiss government and Swiss business interests and the warnings of top EU officials. The result threatens the existing treaties between Switzerland and the European Union that guarantee the free movement of persons, one of the four ‘core’ EU freedoms.

It’s a significant victory for the SVP, which has emerged as a major force in Swiss politics through its forceful advocacy of a nationalist, conservative agenda to restrict immigration and oppose greater EU integration.

The result means that the Swiss government now has three years either to renegotiate or revoke the bilateral agreement finalized in 2002 with the European Union over free movement of persons. That treaty is part of a larger package that provided Switzerland access to the EU single market in exchange for enacting certain aspects of EU policy, and it’s part of a wider process that has more closely integrated Switzerland with the European Union over the past decade. The country’s historic independence means that it’s never seriously pursued EU membership — Switzerland joined the United Nations only in 2002, after all.

Following the 2002 EU-Swiss bilateral agreements, Swiss voters in 2005 took another step toward integration when they approved Swiss membership in the EU Schengen zone, which eliminated passport and immigration checks at the Swiss borders with the rest of the European Union. As recently as February 2009, Swiss voters approved, by a margin of 59.6% to 40.4%, a referendum to extend the freedom of movement of workers from the European Union’s two newest members, Bulgaria and Romania. Today’s vote establishes a legal confrontation with the European Union that the 2009 referendum sidestepped.

The European Commission responded almost immediately with a terse statement:

La Commission européenne regrette que l’initiative pour l’introduction de quotas à l’immigration soit passée via cette votation. Ceci va à l’encontre du principe de libre circulation des personnes entre l’Union européenne et la Suisse. L’Union examinera les implications de cette initiative sur l’ensemble des relations entre l’UE et la Suisse. Dans ce contexte, la position du Conseil Fédéral sur le résultat sera aussi prise en compte.

[The European Commission regrets that the initiative for the introduction of immigration quotas has passed through this vote. This goes against the principle of free movement of persons between the EU and Switzerland. The Union will consider the implications of this initiative on the overall relations between the EU and Switzerland. In this context, the position of the Federal Council on the outcome will also be taken into account.]

Today’s vote causes an immediate dilemma for Brussels. If the European Union agrees to renegotiate the terms of the Swiss bilateral agreement, it will invariably weaken one of the foundational principles of European integration. If Brussels grants concessions to Switzerland, it will almost certainly face pressure to grant similar concessions to EU members, including the United Kingdom, where prime minister David Cameron has pledged to call a referendum on continued British membership in the European Union if his Conservative government is reelected next year.

If Brussels refuses to renegotiate the terms of the agreement, it could face more attacks from far-right politicians and their supporters within the European Union, especially as the continent prepares for the May elections to the European Parliament. Anti-immigration, euroscepetic, right-wing parties lead polls throughout Europe, including Nigel Farage’s United Kingdom Independence Party, Marine Le Pen’s Front national (National Front) in France, Geert Wilders’s Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV, Party for Freedom) in the Netherlands, and Heinz-Chritian Strache’s Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ, Freedom Party of Austria). Today’s Swiss referendum could make immigration within the European Union even more politically relevant in the months ahead.

But the referendum also means significant risks for Switzerland. If the Swiss government is forced to revoke the bilateral treaty on free movement of persons, it could undermine Swiss access to a European single market that now totals more than 500 million people. That would severely disrupt the Swiss economy, which enjoys tariff-free access to the single market, the destination of around 60% of Swiss exports — trade with Germany alone accounts for about 20% of Swiss exports.

Despite the negative headlines that the 2007 poster brought to Switzerland, the Swiss People’s Party emerged from that election with the largest number of seats in the National Council (Nationalrat in German, Conseil National in French), the lower house of the Swiss parliament — just like in the previous 2003 election and the following October 2011 election.

Though it hasn’t received the same attraction as the 2007 poster, the SVP campaigned in 2014 with the same level of subtlety:

It’s line with the SVP’s similar tactics supporting the November 2009 referendum that enacted a constitutional amendment banning the construction of new minarets that won 57.5% of the vote. At the time, there were a total of four mosques with minarets in the country, but the vote brought widespread opprobrium against Switzerland — several European governments and the United Nations voiced concern about whether prejudice motivated the minaret ban and Switzerland’s commitment to freedoms of expression and religion. The SVP was the only major Swiss political party to support the minaret ban, though it did so with vigor — and, again, without subtlety:

But though the minaret ban was politically radioactive, it was largely symbolic. In contrast, today’s immigration initiative could cause serious damage to Swiss-EU economic relations .

SVP tactics haven’t always been successful — Swiss voters rejected a December 1996 initiative ‘against illegal immigration’ and a November 2002 initiative cracking down on asylum, and they widely approved the 2009 referendum extending free movement of workers to Bulgarians and Romanians. Polls showed that today’s initiative would fail, however narrowly.

Yet the SVP tactics have been successful enough over the past decade. In addition to their general election victories, the 2009 minarets ban and today’s immigration victory, the SVP successfully won a November 2010 referendum for an initiative to deport foreigners with criminal backgrounds.

But today’s vote also shows how divided Switzerland remains on immigration, with just 19,516 votes separating the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ camps. Voters in French-speaking cantons, which have historically been least hospitable to the SVP (French-speaking Switzerland was the only part of the country to reject the minaret ban in 2009), rejected the immigration initiative, as did voters in Zürich, the largest Swiss city. Voters throughout the rest of Switzerland, including most of the country’s German-majority and Italian-majority cantons, supported the referendum.

Though there’s an undeniable cultural aspect to the SVP campaign, the SVP largely advanced an economic basis for the initiative, arguing that immigration has resulted in overcrowding, a more difficult job market and downward pressure on wages. What’s most staggering is that the SVP succeeded at a time when the Swiss economy is doing so well. Though GDP growth slumped to 1% in 2012 (partly due to European economic malaise and partly due to the rise in the value of the Swiss franc, which raised the price of Swiss exports), the Swiss economy is expected to reach 2% growth in 2013, and the country has a ridiculously low unemployment rate of 3.2%.

But it’s also true that Switzerland has one of the highest foreign-born populations in the world (and in Europe), with immigrants comprising around 28.9% of the current Swiss population — that’s more than Canada (20.7%), the United States (14.3%), and much more than the United Kingdom (12.4%), Germany (11.9%), France (11.6%) or Italy (9.4%).

Among the top 10 nationalities that represent Switzerland’s permanent residents, six are EU nations, including the top three, Italy (287,995), Germany (275,300) and Portugal (223,667), as well as France, Spain and the United Kingdom. The other four are Serbia, Kosovo, Macedonia and Turkey, each of which has ultimate designs on full EU membership. That means that any meaningful quotas on immigration to Switzerland would almost certainly affect EU nationals — a quota system excluding EU nationals would be essentially symbolic because so many of Switzerland’s foreign-born population comes from within the European Union.

The country’s other three major parties opposed the initiative — including the center-left Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (SPS, Sozialdemokratische Partei der Schweiz in German; PSS, Parti socialiste suisse in French), the classical liberal FDP.The Liberals (FDP.Die Liberalen in German; PLR.Les Libéraux-Radicaux in French) and the center-right Christian Democratic People’s Party of Switzerland (CVP, Christlichdemokratische Volkspartei der Schweiz in German; PDC, Parti Démocrate-Chrétien in French). The three parties currently hold five of the seven seats on the Swiss Federal Council, the executive body that serves as the executive branch of the Swiss government.