By the end of June, the U.S. Supreme Court will render decisions in two of the most important legal cases to affect same-sex marriage in the United States: Hollingsworth v. Perry, which could result in the repeal of California’s Proposition 8, a ballot measure that overturned the state legislature’s enactment of same-sex marriage, and United States v. Windsor, which could strike down the U.S. Defense of Marriage Act. DOMA, a 1996 law that prohibits same-sex couples from federal benefits of marriage, has been struck down by lower U.S. courts as a violation of the ‘equal protection’ clause of the 14th amendment of the U.S. constitution. Others have argued that it violates the right of states to determine their own marriage laws and the ‘full faith and credit’ clause of the U.S. constitution that requires states to recognize the law, rights and judgments of the other U.S. states. ![]()

Both decisions are among the most highly anticipated opinions of the Court’s summer rulings.

But Germany’s top constitutional court, the Bundesverfassungsgericht, got out in front of the U.S. Supreme Court last week with a landmark decision of its own that in many ways mirrors what proponents of same-sex marriage hope will be a harbinger of the U.S. decision on DOMA.

In a decision that could place pressure on chancellor Angela Merkel in advance of Germany’s federal election in September, the constitutional court ruled that same-sex couples in registered civil partnerships are entitled to the same joint tax filing benefits as those in opposite-sex marriages, exactly the rights that DOMA was originally enacted to prohibit in the United States. The decision put the fight for German same-sex marriage on the front page of European newspapers in a summer when the parliamentary battles to enact same-sex marriage in the United Kingdom and France have otherwise dominated headlines.

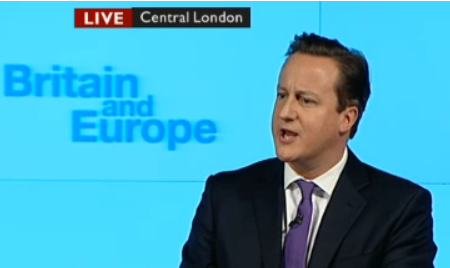

It’s surprisingly in many ways that France and the United Kingdom have been more progressive on same-sex marriage rather than Germany. Although polls show nearly two-thirds of the British and the French support same-sex marriage, a February 2013 poll showed that three-fourths of Germans support same sex-marriage. Moreover, UK prime minister David Cameron is the center-right leader of a Conservative Party that faces its most pressing political pressure today from the right, not from the center, and the virulent anti-marriage rallies in France and the widespread opposition to same-sex marriage on France’s center-right means that French president François Hollande’s push for marriage equality, a policy that he campaigned on in 2012, has met significant turbulence.

But Germany’s evolutionary approach to marriage equality has taken a more subdued path through the constitutional court in Karlsruhe as much as through the Bundestag, Germany’s parliament. Former chancellor Gerhard Schröder and his coalition partner Volker Beck successfully pushed for the enactment of the Life Partnership Act in 2001 when the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party) controlled the government in coalition with Beck’s Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (the Greens). Following the German constitutional court’s blessing of the law in 2002, the Bundestag followed up in 2004 with revisions to the law that increase the rights of registered life partners, including rights to adoption, alimony and divorce, though not parity with respect to federal tax benefits.

Since taking power in 2005, chancellor Angela Merkel has not pushed additional rights for same-sex couples, which puts her at awkward odds with her coalition partners, the Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), which supports marriage equality and whose former leader Guido Westerwelle (pictured above with Merkel), Germany’s foreign minister and its vice-chancellor from October 2009 to May 2011, is openly gay.

Both Merkel’s Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Party) and the CDU’s sister party in Bavaria, the more socially conservative and Catholic-based Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern (CSU, the Christian Social Union in Bavaria), have been traditionally opposed to gay marriage, and as recently as March, the CDU and the CSU reaffirmed their opposition to extending tax benefits to same-sex partners, even though the February 2013 poll showed that two-thirds of CDU-CSU supporters favored same-sex marriage outright.

Despite parliamentary inactivity in Berlin, last week’s decision by Germany’s constitution court, however, is just the latest decision from Karlsruhe that has edged same-sex registered partnerships ever closer to full marriage equality. Continue reading As U.S. awaits DOMA decision, Germany’s constitutional court weighs in on gay rights