<See below Suffragio’s preview of Italy’s February 2013 parliamentary elections, followed by a real-time listing of all coverage of Italian politics.>

Italian voters go to the polls on February 24 and 25, 2013 to select 630 members of the Camera dei Deputati (House of Deputies), the lower house of the Parlamento Italiano (Italian Parliament) and the 315 elected members of its upper house, the Senato (Senate) for a term that can last for up to five years.

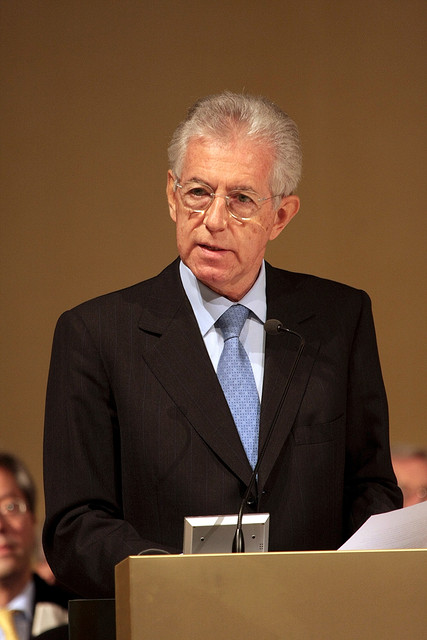

The current prime minister, Mario Monti, was appointed by the Italian Parliament as a ‘technocratic’ prime minister in November 2011 following a crisis over Italian sovereign debt and the resignation of previous prime minister Silvio Berlusconi.

Berlusconi is back, leading the campaign for a center-right coalition comprised of his own party, the Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom), as well as the autonomist party in northeastern Italy, the Lega Nord (Northern League), though Berlusconi has pledged — for now, at least — not to seek to become the center-right’s candidate for prime minister in the event that his coalition wins (though polls show this will be unlikely).

Berlusconi is back, leading the campaign for a center-right coalition comprised of his own party, the Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom), as well as the autonomist party in northeastern Italy, the Lega Nord (Northern League), though Berlusconi has pledged — for now, at least — not to seek to become the center-right’s candidate for prime minister in the event that his coalition wins (though polls show this will be unlikely).

Monti is reluctantly heading a coalition of small parties that hope to return Monti as ‘technocratic’ prime minister, Con Monti per l’Italia) (with Monti for Italy), including a new political party, Scelta Civica (SC, Civic Change) formed for the express purpose of supporting Monti, as well as two smaller center-right parties, the Unione di Centro (UdC, Union of the Centre), which is comprised of former Christian Democrats close to the Vatican and led by Pier Ferdinando Casini, and Futuro e Libertà per l’Italia (FLI, Future and Freedom), a party formed by Gianfranco Fini, once a Berlusconi ally who served as deputy prime minister, foreign minister and as president of the Camera dei Deputati during previous center-right governments.

Berlusconi, who served as prime minister from 1994 to 1996, from 2001 to 2006 and again from 2008 until 2011, has been running a vigorous campaign just as much against Monti and the politics of austerity imposed by Brussels and Berlin as much as the campaign’s frontrunner, Pier Luigi Bersani.

Bersani, who won the primary of the center-left coalition in November 2012 to become its candidate for prime minister, is the leader of the center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), Italy’s main leftist party, and a former government minister, most recently in 2006 to 2008 the minister for economic development. His chief opponent in the center-left primary, Matteo Renzi, currently the mayor of Florence, is supporting Bersani’s campaign, and although he lost the primary to Bersani, his message of generational change has made him one of Italy’s most popular politicians.

Bersani’s coalition also includes the more leftist Sinistra Ecologia Libertà (SEL, Left Ecology Freedom), led by the leftist, openly-gay two-term regional president of Puglia, Nichi Vendola.

Finally, the anti-austerity protest movement led by blogger and comedian Beppe Grillo, the Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) is also polling in double-digits, and it could well win enough seats to force a hung parliament.

Complicated proportional voting

Elections are conducted pursuant to a proportional representation system.

For the Camera dei Deputati, a coalition must win 10% of the total votes nationally in order to win seats, and each party within the coalition must win 2% in order to be allocated seats. Parties outside of coalitions that win at least 4% of the vote will also be eligible for allocated seats. There are 26 electoral districts (each of Italy’s 20 regions has its own district, while Lombardy has three and each of Piedmont, Veneto, Lazio, Campania and Sicily have two), each of which is assigned a number of seats, which are awarded proportionately according to each party’s (or coalition’s) performance in each district.

The coalition (or party) that obtains the largest plurality of votes (but less than 340 seats) is assigned additional seats to reach a 54% majority of the seats.

For the Senato, each of Italy’s 20 regions elects its own senators (with six senators representing Italians who live abroad).

Seats are awarded solely on a regional proportional basis, such that a coalition must win 20% of the vote in a region to win seats (and 3% for each individual party in the coalition), and a party outside of a coalition must win 8% of the regional vote.

In each region, furthermore, the coalition (or party) that wins a plurality is automatically awarded at least 55% of that region’s seats.

In addition to the 315 elected senators, four additional ‘senators for life’ serve in the Senato — each living former president is automatically a ‘senator for life,’ and Italian presidents are permitted to appoint up to five ‘senators for life’:

- Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, formerly Italy’s president from 1999 to 2006, as well as a former longtime governor of the Banca D’Italia, Italy’s central bank, from 1979 to 1993, and a former ‘technocratic’ prime minister from 1993 to 1994.

- Giulio Andreotti, a former Christian Democratic prime minister, also with ties to the Vatican, in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

- Emilio Colombo, another former Christian Democratic prime minister and foreign minister in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

- Mario Monti, as the current prime minister.

Key regional elections to be held simultaneously

Three of Italy’s regions — Lombardy, Lazio, and Molise — will hold elections for their regional governments on February 24 and 25 as well — and each is being conducted under the shadow of PdL scandals.

In Lombardy, Italy’s wealthiest and most populous region, snap elections have been called following the dissolution of its regional legislature by longtime regional president Robert Formigoni in October 2012 after one of his PdL colleagues was arrested for buying votes from the ‘Ndrangheta in the previous 2010 election.

In Lazio, Italy’s third-most populous region, snap elections are being held following another PdL scandal — regional president Renata Polverini dissolved the parliament following charges of misuse of public funds.

Finally, in Molise, Italy’s second-least populous region in the south-central part of the country, regional president Michele Iorio’s victory in the election in October 2011 was declared invalid due to irregularities committed by Iorio and the PdL and, accordingly, new elections will be held in Molise as well.

Italian Parliament must choose a new president

In May, the Italian Parliament will turn to electing a new president of Italy. The current president, Giorgio Napolitano, a longtime moderate member of the once-strong Italian Communist Party and former center-left minister in the 1990s, has said he will not seek a second term.

Although the Italian president is essentially a figurehead, the head of state appoints the prime minister after elections, and is responsible for dissolving the Italian parliament and calling elections. The Italian president is also influential both behind the scenes and in terms of swaying public opinion on important matters of state.

If Monti doesn’t return as prime minister, he would certainly be a top candidate for the presidency. Luca Cordero di Montezemolo, Ferrari’s CEO and a former Fiat CEO, who has recently entered politics in favor of Monti, has said he would also be a candidate for the presidency. If the center-left wins an overwhelming mandate, Massimo D’Alema, a longtime fixture of the Italian center-left (prime minister from 1998 to 2000 and minister of foreign affairs from 2006 to 2008) could emerge as a leading candidate — he was a candidate in the prior 2006 election.

Other center-left candidates might include Giuliano Amato, a former ‘technocratic’ prime minister from 1992 to 1993 and 2000 to 2001 and most recently interior minister from 2006 to 2008), or even Romano Prodi, prime minister from 1996 to 1998 and 2006 to 2008 and president of the European Commission from 1999 to 2004.

The presidential election is conducted among both houses of the Italian Parliament, as well as among a special group of 58 ‘electors’ appointed by each of Italy’s 20 regions.

A two-thirds majority is required on the first three ballots, but starting on the fourth ballot, a simple majority is sufficient to elect a president.

* * * * *

Please find below Suffragio‘s posts covering Italian politics:

Renzi, Berlusconi team up for electoral law pact

January 21, 2014

In dismissing Fassina, Italy’s Renzi marks his ‘Sister Souljah’ moment

January 14, 2014

Renzi wins Democratic Party leadership in Italy, establishing rivalry with Letta

December 9, 2013

Rise of new Italian political leadership eclipses Berlusconi’s expulsion from the Senate

November 18, 2013

What the Alfano-Berlusconi split means for Italian politics

November 18, 2013

Letta dicusses political stability in Washington on day after US gov’t shutdown ends

October 17, 2013

Letta survives no-confidence vote easily as Berlusconi suffers humiliating defeat

October 2, 2013

Does this week’s political crisis in Italy represent Berlusconi’s last stand?

September 30, 2013

Berlusconi verdict plunges Italian right (and everyone else) into uncharted territory

August 1, 2013

Italy’s problem with racism goes far deeper than recent slurs against Cécile Kyenge

July 16, 2013

Don’t read too much into Marino’s center-left victory in Roman mayoral election

June 11, 2013

Rome mayoral race heads to tense June runoff between center-left, center-right coalition partners

May 28, 2013

Former Italian prime minister Giulio Andreotti is dead

May 6, 2013

Letta unveils government short on Berlusconi allies, long on economists

April 27, 2013

Who is Enrico Letta?

April 24, 2013

Napolitano’s in (again), Bersani’s out, and Italy’s as dysfunctional as ever

April 20, 2013

Prodi falls far behind on fourth Italian ballot

April 19, 2013

Prodi emerges as united center-left’s presidential candidate in Italy

April 19, 2013

Presidential vote returns Italian politics to high operatic drama

April 18, 2013

Seven people who could be appointed Italy’s next technocratic prime minister

March 28, 2013

Italian government now rests in hands of Napolitano, Italy’s president

March 28, 2013

Does Pier Luigi Bersani believe in miracles?

March 25, 2013

Pier Luigi Bersani has five days to build an Italian government

March 22, 2013

How would Italian politics function under a French electoral system?

March 6, 2013

Maroni’s Lombardy victory consolidates Northern League’s regional hold

February 27, 2013

More thoughts on the final Italian election results and Italy’s election law

February 26, 2013

Where Italy goes from today’s elections: A look at four potential outcomes

February 25, 2013

Making sense of today’s Italian election results

February 25, 2013

The role of Italy’s south in this weekend’s election

February 24, 2013

What will Italy’s election mean for LGBT rights?

February 22, 2013

What kind of Italian prime minister would Angelino Alfano make?

February 20, 2013

History shows Italy’s center-left coalition will likely be short-lived and tenuous

February 20, 2013

Monte dei Paschi scandal gives share of blame to Italian left, right and center

February 19, 2013

What the papal abdication means for Italy’s upcoming general election

February 14, 2013

How the Italian election, Bersani’s to lose, became a Berlusconi-Monti dogfight

February 13, 2013

Center-left poised to block nationalist Storace’s comeback in Lazio

February 5, 2013

Lombardy looks to post-Formigoni era in toss-up regional elections

February 4, 2013

Italian prime minister Mario Monti has a ‘Goldilocks’ problem

January 3, 2013

Monti resigns as prime minister in light of Berlusconi’s political return

December 10, 2012

Five reasons Berlusconi returned to run in the upcoming Italian election

December 8, 2012

Bersani routs Renzi in ‘centrosinistra’ primary to lead Italian left next spring

December 3, 2012

Bersani leads as Italian ‘centrosinistra’ primary heads to Sunday runoff

November 28, 2012

Bersani and Renzi offer two distinct personalities for Italy’s center-left

November 19, 2012

Crocetta likely to become Sicily’s first openly-gay, first leftist president

October 30, 2012

Incredibly low turnout in Sicilian election

October 29, 2012

Today’s Sicilian elections showcase potential party strength before 2013 Italian election

October 28, 2012

Berlusconi convicted of tax fraud, sentenced to four years in prison

October 26, 2012

Is Italy headed into a post-Berlusconi ‘third republic’ era of national politics?

October 11, 2012

Is the European ‘Christian democracy’ party model dead?

September 4, 2012

Il ritorno del Berlusconi — why his re-emergence in Italian politics is completely logical

July 31, 2012

Addio to the Lega Nord

April 20, 2012

* * * * *

Photo credit to Kevin Lees — Duomo in Florence, September 2006; Tiber river and the Vatican in Rome, November, 2011.

![]()