Earlier today, Suffragio kicked off its 2013 coverage of world politics with a look at 13 key elections to watch in 2013.

While we’ll watch as new leaders, from Egyptian president Mohammed Morsi to French president François Hollande to South Korean president Park Geun-hye begin their first full years of power, we’ll also watch for comebacks by former presidents — former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva will make a decision about running for a third term in the 2014 Brazilian presidential election and former Chilean president Michelle Bachelet is the odds-on frontrunner to win a new term in Chile’s December 2013 election.

In addition, however, here are 13 up-and-coming politicians and other public figures who will figure prominently in the next 12 months — either because they are likely to come to power themselves in 2013 or because this year will will likely be a make-or-break year for them to achieve power beyond 2013.

1. Tarō Asō

Happy days are here again for Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō), which has returned to power with a vengeance after three years of governments from the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō), which was nearly wiped out in the December 2012 parliamentary elections.

One of the most interesting appointments that returning prime minister Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三) made was that of Tarō Asō as Japan’s new finance minister. Asō, like Abe, is a former prime minister — he served from September 2008 to September 2009, during which Japan absorbed the brunt of the world economic crisis. That experience will come in handy for Asō, given Abe’s incredibly bold plans to goose the Japanese economy with massive amounts (to ¥200 trillion, or around $2.4 trillion) of public spending and a campaign to push the Bank of Japan to adopt a higher inflation target to pull Japan out of its low-growth, deflationary state. Asō will also play a role in choosing the next Japanese central bank governor in April 2013.

Abe’s government is the seventh in seven years, and given the rate at which Japan goes through prime ministers, it’s not incredibly outlandish to think that Asō could also have another go at the top job in 2014 or 2015, especially if the economic reforms that Abe’s proposed manage to turn around Japan’s two-decades long malaise.

* * * *

2. Mark Carney

It was quite a coup for the United Kingdom to select Carney as the new governor of the Bank of England — he’s currently governor of the Bank of Canada, so will not need a whole lot of on-the-job training. When he succeeds Mervyn King in July of this year, he will become the top monetary policymaker for the world’s sixth-largest economy and Europe’s third-largest, and he will do so at a time when the Bank of England will have enhanced policymaking powers, including with respect to bank capital requirements.

Given the budget cuts pursued by the United Kingdom’s Conservative-led coalition government, Carney may well take a more aggressive stance to use monetary tools to boost the sagging British economy. As Canada’s central bank governor during the 2008-09 financial crisis, he joined U.S. Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke in pursuing extremely low interest rates and providing additional liquidity to the Canadian economy.

Certainly he’ll play a role in setting the conditions under which the next UK general election will be held, likely in May 2015. But he’s already among the most highly regarded members of the relatively small club of central bank governors — given his experiences in both Ottawa and London, and that Bernanke is expected to step down in 2014, markets may look to him even more than Bernanke’s successor in setting the pace of global monetary policy.

* * * *

3. Ed Miliband

At the close of 2012, the United Kingdom’s Labour Party had achieved its largest poll lead since the pre-Iraq days of Tony Blair’s popular ‘New Labour’ government in the early 2000s.

Although the next election is not expected until May 2015, the British are nonetheless closer to the next election than the last one in May 2010, which ended Labour prime minister Gordon Brown’s beleaguered government and brought about a government coalition led by the Conservative Party under prime minister David Cameron, with support from the Liberal Democratic Party.

The budget cuts that Cameron — and his chancellor George Osborne — continue to pursue have left the government incredibly unpopular, with some economists charging that the emphasis on austerity has exacerbated an economy that’s now in a double-dip recession. The tensions are obvious within the coalition government, and the Liberal Democrats have fallen behind the nationalist and euroskeptic United Kingdom Independence Party in many polls.

But voters may not yet have confidence in Miliband, who defeated his more experience brother David Miliband, a former foreign secretary, in September 2010, with the support of much of Labour’s more leftist elements, including its labour and trade unions. If the fresh-faced Miliband — who served for just two years as energy and climate change minister in Brown’s government — is to be successful, the coming year will be vital in demonstrating that he can fill the role of prime minister. Despite the wide lead in polls, voters remain especially hesitant about Labour on economic matters and,in particular, the pugnaciously pro-growth shadow chancellor Ed Balls.

* * * *

4. Uhuru Kenyatta

Kenyatta, the son of Kenya’s first president from 1964 to 1978, Jomo Kenyatta, has been a presence in Kenyan politics for over a decade, and he has at least even odds of winning Kenya’s March presidential election.

But given that the International Criminal Court has indicted him — and his running mate, William Ruto — for allegedly supporting and inciting ethnic-based violence in the aftermath of the 2007 presidential election, his victory in the March 4 presidential election in Kenya would cause some amount of alarm, both domestically and internationally.

If he does win the election, his first immediate test will be to ensure that the 2013 results don’t lead to the kind of bloodshed that followed the 2007 election and thereupon, to find a way to avoid Kenya’s transformation into an international pariah led by someone under suspect of crimes against humanity. It will require Kenyatta to transcend much of the divisiveness that’s marked his political career, not to mention the Kikuyu ethnic community from central Kenya to which Kenyatta belongs.

Kenyatta has served as deputy prime minister since 2008 and served as finance minister from 2009 until the ICC’s charges were filed in early 2012.

* * * *

5. Azeb Mesfin

When Ethiopia’s Meles Zenawi died in August 2012, many feared that the country would descend into violence — after all, the two prior transfers of power in 1974 and 1991 came as a result of violent coups, in the wake of revolution and civil war.

Yet power, for now at least, has peacefully transferred to newly appointed prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn, the former deputy prime minister and foreign minister since 2010. He was an odd choice to succeed Meles, and he is the first Ethiopian leader to come from the country’s south. That may have, counterintuitively, led to a more peaceful result than elevating any of the various members of the Tigray ethnic group to which Meles belonged, and which dominates the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF, or የኢትዮጵያ ሕዝቦች አብዮታዊ ዲሞክራሲያዊ ግንባር).

Among those Tigray power-brokers is Meles’s widow, Azeb Mesfin, who has designs over her own to rule Ethiopia one day. Mesfin, who also fought in the Tigray rebel forces against the communist Derg government that fell in 1991, is currently a member of Ethiopia’s parliament and as first lady, she served as an activist for causes ranging from HIV/AIDS to women’s rights to mental health. She refused to leave the presidential residence until late October, however, and is seen as among the strongest contenders that could emerge to challenge Hailemariam’s government.

Hailemariam will not face elections until 2015, but the real challenge will be for him to consolidate power far sooner, lest Mesfin or another member of the powerful Tigray People’s Liberation Front (the TPLF, ሕዝባዊ ወያኔ ሓርነት ትግራይ) within the EPRDF, which retains control over the country’s security, police and intelligence powers, edge him out of power.

* * * *

6. Justin Trudeau

The son of fondly regarded former prime minister Pierre Trudeau burst onto Canada’s national scene in 2000 with a eulogy of his father, and later in 2008, when he was elected to Canada’s House of Commons from a riding outside Montreál.

Although the long-troubled Liberal Party isn’t selecting its new leader until April, it’s all but certain that Trudeau will be the next leader of the party, amid euphoric favorability — polls show that Trudeau would boost the Grits from a ten-point deficit in third-place to leading all parties with a seven-point lead, and the expectations are that Trudeau alone can bring the Liberals back into contention to govern Canada. Yet when he takes over the party’s leadership, those breakneck expectations are likely to be his biggest threat when he’s less the embodiment of the more nobler aspects of his father’s era and just a pol like everyone else in Ottawa — and without any experience in government and without even much experience in the federal politics.

But he still likely represents the best chance for the Liberals to stop the progress of the socially democratic New Democratic Party, which supplanted the Grits in the last Canadian election to become the official opposition. After a long line of uninspired or uncharismatic leaders — former prime minister Paul Martin, former environmental minister Stéphane Dion, author Michael Ignatieff and current interim leader and former NDP premier of Ontario Bob Rae — Trudeau is probably the last chance for a party that dominated Canadian politics throughout much of the 20th century.

* * * *

7. Rahul Gandhi

If Trudeau is heir to the legacy of a famous Canadian prime minister, Gandhi is heir to the legacy of over half a century of Indian political dynasty, for better or worse, and he is set to lead the Indian National Congress party (Bhāratīya Rāṣṭrīya Kāṅgrēsa) in the expected 2014 elections for control of the Lok Sabha ( लोक सभा), the lower house of India’s parliament.

He is the son of Congress president Sonia Gandhi, the son of the former prime minister from 1984 to 1989, Rajiv Gandhi (assassinated in 1991), the grandson of former prime minister from 1966 to 1977 and 1980 to 1984, Indira Gandhi (assassinated in 1984) and the great-grandson of India’s first prime minister from 1947 to 1964, Jawaharal Nehru.

With a pedigree like that, Gandhi has fairly high expectations. He’s taken an increasing role in Congress’s leadership, although he’s been somewhat of a less than inspiring figure. In 2014, he will face an Indian electorate wary of power infrastructure issues that have led to massive blackouts and an economy that’s cooling off after over a decade of robust growth, to say nothing of the current protests stemming from the gang rape and death of a 23-year-old girl in Delhi last month. In order to win a third consecutive Congress term and to succeed Manmohan Singh as prime minister, Gandhi will have to defeat a resurgent conservative Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, or भारतीय जनता पार्टी), the conservative and Hindu nationalist party likely to be led by Gujarati chief minister Narendra Modi, who won in late December 2012 reelection to a fourth term, despite active campaigning from both Gandhis and Singh. Much of the groundwork for the 2014 campaign, however, will need to be accomplished this year.

Despite Gandhi’s campaigning in the regional elections in Uttar Pradesh — India’s most populous state with 200 million people — in January 2012, Congress failed to win the elections, which were swept by the regional socialist Samajwadi Party.

* * * *

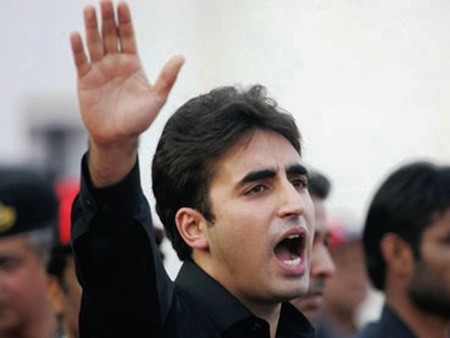

8. Bilawal Bhutto Zardari

Next door to India, yet another famous son is rising in Pakistan, where the 24-year-old Zardari just last week stepped out of the shadows for his political debut in one of the world’s messiest democracies.

Ahead of elections expected this spring in Pakistan, Zardari will take an increasingly dominant role on behalf of the ruling Pakistan People’s Party (اکستان پیپلز پارٹی, or the PPP), despite headwinds that show the more conservative Pakistan Muslim League (N) (اکستان مسلم لیگ ن, or the PML-N) in a better position and with Nawaz Sharif a favorite to return as prime minister. If the PPP wins the elections, however, it remains doubtful that the still-young Zardari would become prime minister, although he would likely assume some form of governmental responsibility. It may well be better for Zardari for Sharif to take power in the meanwhile, as Zardari gains some more experience.

Zaradari’s father, Asif Ali Zardari, is Pakistan’s president, and he’s been at the center of the ongoing tussle between the PPP’s governments and the Supreme Court over executive prerogative with respect to Swiss charges of graft against Zardari.

The son of Benazir Bhutto, Pakistan’s former prime minister who was assassinated in 2007 upon her return to the country to campaign for elections, he has been touted ever since to follow in his mother’s footsteps, prematurely acceding to the leadership, as co-chair with his father, of the PPP in 2007 after his mother’s death, although he only returned to Pakistan in 2011 following his studies at Oxford University in the United Kingdom.

* * * *

9. Jean-Claude Juncker’s successor

Jean-Claude Juncker, prime minister of tiny Luxembourg since 1995, and head of the Euro Group since 2005, announced in December 2012 he would step down from his role leading the Euro Group, the committee of eurozone finance ministers that effectively represents the controlling political authority over the European single currency.

Juncker, when he was appointed in 2005, was essentially the first to take over the position with additional policymaking powers, and it has taken on increasingly pivotal role in setting the political agenda for economic and financial reforms for the eurozone.

Juncker’s successor, therefore, will be a critical player in determining any future European bailout policy, the implementation of the EU fiscal compact on budget control and future banking union and additional fiscal harmonization.

It seems unlikely that either the pro-growth French finance minister Pierre Moscovici of the center-left Parti socialiste or the pro-austerity German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble of the center-right Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, Christian Democratic Union), will succeed Juncker, given that they lie on opposite poles of the austerity/growth debate currently raging in Europe. But it’s certain that the ultimate choice will have to be acceptable to both the French and German governments.

As such, in recent days, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, who became finance minister of the Netherlands only in November 2012, has been touted as a compromise candidate. Although Dijsselbloem belongs to the social democratic Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA, Labour Party), which campaigned on a platform of a more pro-growth, gentler path toward balancing the Dutch budget, he serves as the finance minister of a coalition government led by prime minister Mark Rutte’s Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy), which remains committed to reducing the Dutch budget deficit to 3% of GDP in 2013.

Other possible candidates include Finnish prime minister Jyrki Katainenis; Olli Rehn, a Finnish politician service as vice chair of the European Commission, and as commissioner for economic and monetary affairs and the euro; Irish finance minister Michael Noonan; and Werner Faymann, the social democratic chancellor of Austria.

* * * *

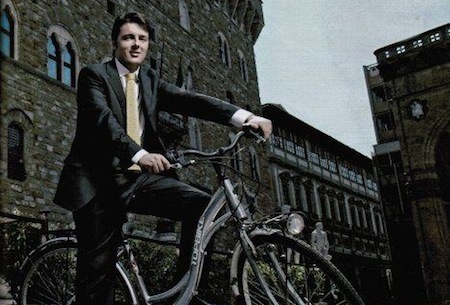

10. Matteo Renzi

Although he lost the ‘centrosinistra‘ primary among the various parties of Italy’s center-left to select a consensus candidate for prime minister, Renzi has established himself, at age 37, as the face of the future of Italian politics.

Renzi’s rival in that primary, the more staid Pier Luigi Bersani, however, will need Renzi’s help in the next two months before Italy’s election to boost the chances of the center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), as Renzi remains the most popular politician in the country. The mayor of Florence in Tuscany, Renzi argued during the primary that the current generation — including Bersani, as well as former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi — should stand down to make way for a new generation of leadership in Italy. As such, Renzi, who’s perceived as more to the center than many of the most recent PD and center-left leaders, is seen as somewhat of a third-way leftist in the mold of former UK prime minister Tony Blair.

Regardless of how the election turns out, Renzi has established himself as the heir apparent of the Italian left. If Bersani becomes prime minister, Renzi could well become a top member of the government if he so desires.

* * * *

11. Naftali Bennett

Bennett is now indisputably the man of the hour with just three weeks to go before Israel’s parliamentary election. Bennett leads a coalition of right-wing parties Bayit Yehudi (הבית היהודי, ‘The Jewish Home’) that looks to win between 15 and 20 of the seats in the 120-member Knesset, Israel’s unicameral parliament. That would make Bennett a key power-broker in any coalition led by Benjamin Netanyahu — and with the resignation and continuing legal problems of foreign minister Avignor Lieberman, Bennett could even become foreign minister after the election, and will almost certainly hold some cabinet role. Bennett’s ties to Netanyahu are strong, given that he served as Netanyahu’s chief of staff from 2006 to 2008. Bennett was born to American migrants to Israel and spent his 20s in New York City making his fortune as a tech entrepreneur, so has strong ties to the United States as well.

Nonetheless, Bennett remains firmly to the right of Likud and Netanyahu, especially on the Palestinian peace process. Bennett opposes a two-state solution, which Likud has endorsed, and he caused an uproar recently when he argued that, if he were serving in the military, he would refuse orders to evacuate Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

* * * *

12. Luis Videgaray

Videgaray has long served as the chief consigliere to newly inaugurated Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto — first as finance secretary when Peña Nieto was just the governor of the state of México and he led Peña Nieto’s campaign in what turned out to be a relatively easy win in the July 2012 presidential election. And although Peña Nieto’s victory returned the once-hegemonic Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) to power after 12 years out of power, Videgaray is not your grandfather’s priista. He’s the most well-known of a cadre of young priistas that now hold much (but not all) of the power within the PRI — Videgaray is more Ernesto Zedillo than Carlos Salinas.

As the minister of finance and public credit in Peña Nieto’s cabinet, he will be at the center of the Mexican economy for the foreseeable future, and he’ll likely take the lead in educational and economic reforms that Peña Nieto wants to enact, many of which the outgoing center-right Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) will also likely support — including the reform and perhaps partial privatization of Pemex, the state-owned oil company.

Though Peña Nieto came to the Mexican presidency from outside federal politics, it seems likelier that the PRI’s candidate to succeed him in 2018 will come from within the circles of federal power, in the same way that former Guanajuato governor Vicente Fox, who brought the PAN to power after 71 years of PRI rule in 2000, was succeeded by his energy minister, Felipe Calderón, in 2006.

That means that Videgaray could be well-placed to run in 2018, especially as México’s economy continues to grow — it’s expected to overtake Brazil’s as Latin America’s largest economy within a decade or so.

* * * *

13. Wang Yang (汪洋)

Although Wang wasn’t selected to join the slimmed-down seven-member Politburo Standing Committee, the outgoing Guangdong secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) remains perhaps one of the most well-known rising leaders within the Party, not just as an economic reformer — not necessarily so unique, given that continued Chinese GDP growth practically requires innovative government — but as a political liberal, relatively speaking. Although he has not pushed for anything as radical as, say, free elections, he has taken a less heavy-handed approach to dissent. That may be due to Guangdong’s relative proximity to the liberal Hong Kong, which features much greater economic and political freedoms.

He was replaced in December 2012 as party secretary in Guangdong by rising star Hu Chunhua, who has most recently served as party chief in Inner Mongolia, Wang pushed to transform the province, China’s most populous with 105 million people, from being the world’s manufacturing capital to featuring a more lucrative technology-based economy.

Wang remains a member of the wider 25-member Politburo, however, and it’s not unlikely that he’ll become a vice premier, perhaps, in the incoming government of premier Li Keqiang ( 李克强). Although he was passed over in 2012 for membership on the Standing Committee, all five of the newly appointed members will be too old to be reappointed when the Party is expected to hold another National Congress in 2017 and, at 57, Wang remains young enough to remain in top contention then.

Top image credit to scanrail / 123RF Stock Photo.

2 thoughts on “13 in ’13: Thirteen up-and-coming world politicians to watch in 2013”