No one could miss the undertones of yesterday’s op-ed, co-written by US president Barack Obama and French president François Hollande, in The Washington Post and Le Monde:

No one could miss the undertones of yesterday’s op-ed, co-written by US president Barack Obama and French president François Hollande, in The Washington Post and Le Monde:![]()

A decade ago, few would have imagined our two countries working so closely together in so many ways. But in recent years our alliance has transformed. Since France’s return to NATO’s military command four years ago and consistent with our continuing commitment to strengthen the NATO- European Union partnership, we have expanded our cooperation across the board. We are sovereign and independent nations that make our decisions based on our respective national interests. Yet we have been able to take our alliance to a new level because our interests and values are so closely aligned.

It was one of the biggest, wettest, sloppiest kisses that the Obama administration has given a foreign leader — and it’s not something that this administration does often. It’s part of the red-carpet treatment that Obama is rolling out for Hollande, who visited Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson, in Virginia on Monday, and will be the host of a state dinner tonight at the White House.

It’s clearly an opportunity for the newly single Hollande to move on after a dismal January, when sensational headlines over his trysts with a French actress overshadowed his his attempts to introduce a new economic reform package. It became a nearly monthlong saga that sent Hollande’s partner, Valerie Trierweiler, to a Paris hospital for over a week, and that ended with their breakup.

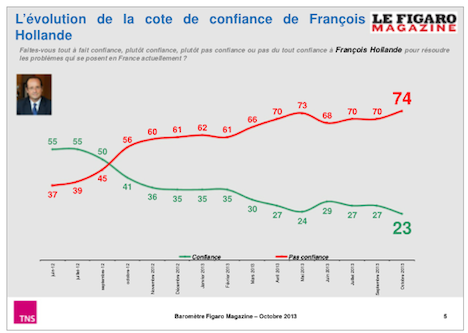

Time magazine, which a wide-ranging interview, asks this week on its cover whether Hollande can fix France. It’s worth asking whether, first, the White House is trying to help fix Hollande. Polls routinely show Hollande with an approval rating in the low 20s (or even high teens), making him the least popular president in the history of the Fifth Republic, not even two years into his five-year term.

The White House treatment, including Monday’s joint editorial, undoubtedly hopes to share of Obama’s star power with the widely derided president. Obama needs Hollande’s help to finalize the US-EU free trade pact, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, even though it could harm French farmers and wine producers by opening the European Union to cheaper US exports. Obama will also need Hollande’s help to win a long-term nuclear energy deal with Iran while the temporary six-month deal remains in effect.

It’s true that France has been, surprisingly, almost as reliable a partner on US foreign policy as the United Kingdom in recent years. Hollande has deepened France’s 21st century internationalism, of course, most notably through his decision to mount a largely successful intervention to keep northern Mali from falling to foreign Islamic jihadists, thereby giving Bamako the space to hold new elections and build a stronger national government. French peacemakers in the Central African Republic may have also helped limit violence between Christians and Muslims in December and January and smoothed the way for Michel Djotodia’s resignation. Hollande was willing to back a US military attack on Syrian president Bashar al-Assad last August when the United Kingdom and the US Congress were not.

But credit for the hard work of repairing US-French relations, insofar as it relates to the newly muscular tone of French foreign policy, more appropriately rests with former president Nicolas Sarkozy, whose administration marked the true pivot on foreign policy. Continue reading Can the Obama administration save François Hollande?