In a more developed democracy, Côte d’Ivoire’s October 25 election might have been a civil rematch of the 2010 contest between the incumbent, Alasanne Ouattara, and his fierce rival, former president Laurent Gbagbo.![]()

Instead, Gbagbo is imprisoned at The Hague in The Netherlands awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court as the first head of state to be tried for crimes against humanity that stem from Gbagbo’s refusal to step down from the Ivorian presidency after the 2010 elections, setting the country into its second civil war in a decade as Gbagbo and his allies clung to power.

Captured in 2011 by UN and local forces loyal to Ouattara, Gbagbo still retains a loyal following, and supporters want to see Gbagbo freed.

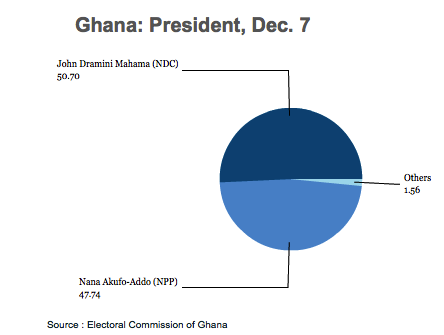

Instead, Ouattara easily won the presidential vote, election officials announced last week, effortlessly dispatching Pascal Affi N’Guessan, formerly prime minister under Gbagbo from 2000 to 2003 and a longtime Gbagbo supporter.

Ouattara, of northern descent, served as Félix Houphouët-Boigny’s final prime minister from 1990 until the former president’s death in December 1993. Though he attempted to run for president in 1995 and 2000, opponents like Robert Guéï, the country’s military leader from December 1999 to October 2000, managed to have him barred from the race on specious charges that Ouattara was actually born in neighboring Burkina Faso, inflaming northern Muslims by implying that they are something less than fully Ivorian. An economist, Ouattara spent the late 1990s at the International Monetary Fund, where he rose to the rank of deputy managing director. The struggle over the 2000 election and its aftermath directly led to the civil war that broke out in 2002.

Former president Laurent Gbagbo, who once represented the hopes of the Ivorian opposition, now sits in The Hague awaiting an ICC trial for crimes against humanity.

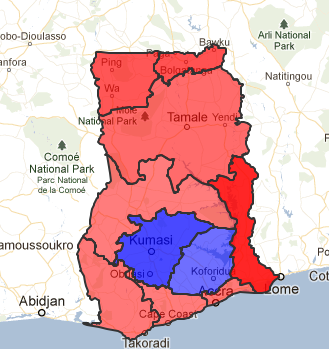

Ouattara officially won 82.66% to just 9.29% for N’Guessan, though many of Gbagbo’s supporters boycotted the vote. That means that the lopsided victory obscures the fact that Côte d’Ivoire remains highly divided on north-south lines.

Though it might have been a less-than-scintillating contest, it is perhaps remarkable that the country made it through an election without major violence — a consequence aided by the fact of an ongoing 6,000-strong UN peacekeeping force, an international presence for over a decade. Continue reading Ouattara wins expected lopsided victory in Côte d’Ivoire