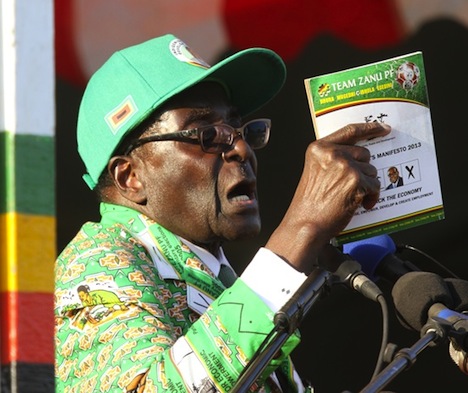

It’s easy to forget that when Robert Mugabe first came to power in 1980, after a long guerrilla campaign against the white minority rule of Ian Smith in what was then still known as Rhodesia, life in Zimbabwe was optimistic. ![]()

A tale of post-colonial hell

Despite his declarations that he wanted a one-party Marxist state as the more aggressive of three competing nationalist leaders, Mugabe (pictured above), the leader of the ZANU-PF (Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front) overwhelmingly won Zimbabwe’s first majority-rule election with just a hint of the political intimidation and violence that would be a harbinger of Mugabe’s rule to come. After the initial 1980 vote, with an air of magnanimity, Mugabe ushered in a post-independence era of optimism. He refused to harass the white minority of Zimbabwe, even retaining Ken Flower, Zimbabwe’s chief intelligence official, who had once been responsible for trying to assassinate Mugabe. More importantly for the black majority that could now express representative power in the country, Mugabe briskly set about enacting a program of improving education and health care for the masses, with promises of long-awaited land reform to come.

The honeymoon didn’t last long, and Mugabe turned first on his fellow nationalist rebels, the ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People’s Union), whose leader Joshua Nkomo initially served as secretary of home affairs in 1981 and 1982. Mugabe, who called Nkomo a ‘cobra in a house,’ turned on the ZAPU following a trumped-up scandal over alleged ZAPU arms caches, added that, like a cobra, Nkomo should be attacked and his head destroyed. Mugabe, who had been clandestinely constructing a secret ‘fifth brigade’ of soldiers loyal to Mugabe alone, began what would be a five-year campaign to subjugate the ZAPU. The fight took on the ugly shades of ethnic cleansing for the next five years, with the ZANU-PF and military brigades loyal to Mugabe, from the Shona ethnic group, largely harassing — and in some cases using a food embargo with the active goal of starving — the ZAPU supporters, largely based in southwestern Zimbabwe among the Ndebele ethnic group.

About 80% of Zimbabwe’s population of 12.75 million people today is Shona, an ethnic group that predominates throughout Zimbabwe and parts of southern Mozambique and that speaks Shona, a Bantu family language. But another 15% of the population belongs to the Ndebele ethnic group, which is clustered in the two provinces of Matabeleland, especially in the south (see below a province-level map of Zimbabwe’s 2008 results, which show Matabeleland, even two decades later, is an area of anti-Mugabe sentiment). Their northern Ndebele language is also a Bantu language, but belongs to the separate Nguni group of languages that also includes Zulu and Xhosa, the former nearly universally understood in South Africa and the latter an important minority language of about one-fifth of southeastern South Africa, and Swazi, spoken largely in Swaziland.

Notwithstanding the violence, residents in Matabeleland voted overwhelmingly for the ZAPU in the 1985 parliamentary elections, which led to ever more oppression. Nkomo essentially surrendered two years later, and Mugabe signed a unity agreement in 1987 that formally merged the ZAPU into the ZANU-PF and offered a general amnesty from an otherwise needlessly brutal effort to establish a one-party state.

In the meanwhile, the optimism with which a newly independent Zimbabwe launched had flagged. Mugabe had already begun his longstanding campaign against white settlers in Zimbabwe with threats of expropriation of land, and the economy had already started its long, slow retreat under the weight of Mugabe’s new social spending, the inefficiencies of state-run industry and the rampant corruption that increased with Mugabe’s patronage-based rule. Continue reading Zimbabwe looks to ghosts past, present and future in key general election vote today