Among the more famous — and unique — provisions of the world’s constitutional jurisprudence is the Japanese constitution’s pacifist Article 9, which prohibits any act of war by the state.

The English translation of the article reads as follows:

Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.**

Traditionally, Article 9 has limited Japan’s military capability since World War II to a merely defensive capacity, with the country largely dependent on the United States for its external security.

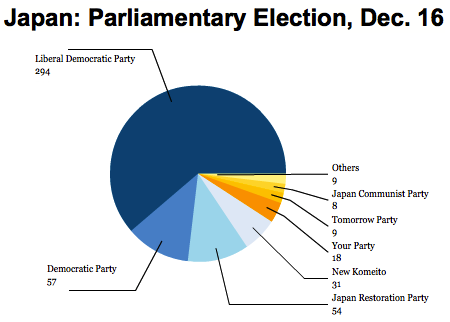

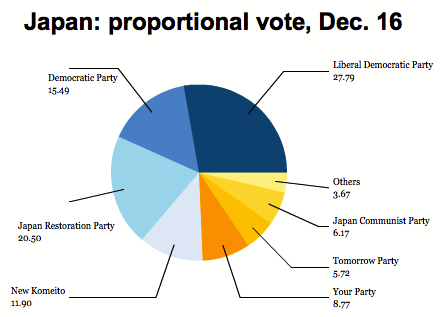

But with tensions already high and rising with the People’s Republic of China over three of the tiny Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu in Chinese) since the Japanese government formally purchased the islands in September, and with the relatively more militant Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三), leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō), increasingly set to win Japan’s snap elections on December 16 for the lower house of Japan’s parliament, the Diet, Article 9 may be set for reinterpretation.

Abe comes naturally to his more hawkish views on Japan and its military power. As prime minister from 2006 to 2007, he tried to push a stronger interpretation of Article 9 and pursued a more aggressive foreign policy. Moreover, as prime minister and most recently after winning the leadership of the LDP, he visited the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, which honors Japan’s war dead, including several war criminals, a move that has consistently provoked China and South Korea. Abe’s grandfather Nobusuke Kishi (岸 信介) served as Japan’s prime minister from 1957 to 1960 and counts among his major accomplishments the signing of the mutual cooperation and security treaty between Japan and the United States.

Although Japan’s election campaign has also featured nuclear energy policy, the current government’s recent increase in the country’s consumption tax and economic policy for pulling Japan out of more than two decades of economic slump, the Senkaku showdown with China has highlighted Abe’s stance to revise the government’s interpretation of Article 9, at a minimum, to allow for collective self-defense. Such a relatively more aggressive interpretation would allow Japan to join allies, such as the United States, in military actions throughout the world or possibly even join collective security alliances such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (Japan is already a major ‘non-NATO ally’). Although all of Japan’s postwar administrations have interpreted Article 9 to prohibit such a wide interpretation, Abe and his LDP allies would prefer the capability to deploy Japanese forces alongside, for example, U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

In a sense, it’s ridiculous to say that Japan doesn’t have a military. Its Self-Defense Force was created as an arm of the Japanese defense department in 1954, and it’s consistently grown ever since. Although it’s technically not an army, Japan’s active forces (around 250,000) are a bit larger than either of Germany’s or the United Kingdom’s active forces. True, under Japan’s complicated national defense policy, the Self-Defense Force is limited to exclusively defense-oriented policy, and Japan has refrained from developing nuclear weapons and traditionally worked in random to develop security arrangements with the United States.

But Japan itself has been stretching its interpretation of Article 9 for years — from 2004 to 2006, notably, Japan sent forces to Iraq to assist the United States in its occupation of Iraq, and in the past decade, Japan has become increasingly at ease with sending Self-Defense Force troops abroad to assist in humanitarian and peacekeeping arrangements, typically under the aegis of the United Nations.

The LDP’s return to government — it essentially controlled Japan from 1955 to 2009 — could not only result in a more aggressive interpretation of Article 9 to allow collective self-defense, but the re-christening of the Self-Defense Force as the more militaristic National Defense Force, and a full-fledged revision of Article 9 to allow Japan to have a full military like any other country, especially as the memory of Japan’s imperial army during World War II fades from memory and Japan feels increasingly vulnerable from a strengthening Chinese presence in East Asia. Continue reading Power, destruction, and Hello Kitty: Article 9, the Self-Defense Force and Japan’s election campaign →

![]()