Earlier this month, voters went to the polls in Belarus to elect the country’s rubber-stamp parliament under its authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko and, in what amounts to democratic liberalization, two opposition MPs were elected to the 110-member assembly from the constituency that contains Minsk, the capital.![]()

![]()

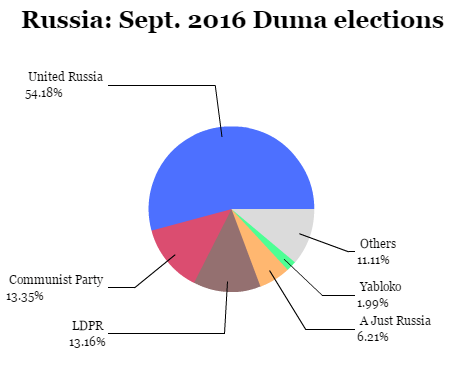

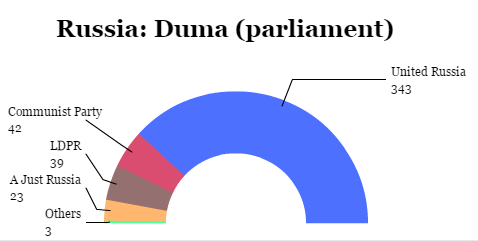

Last weekend, a higher number of opposition MPs were elected to the state Duma (ду́ма), the lower house of the Russian federal assembly, when Russian voters took to the polls on September 18. Nevertheless, despite the unfair and unfree nature of Russian elections, an electoral rout for president Vladimir Putin’s United Russia (Еди́ная Росси́я) means that Putin will now turn to the presidential election scheduled for 2018 with an even tighter grip on the Duma after United Russia increased its total seats from 238 to 343 in the 450-member body. As predicted, Putin took fewer chances in the September 18 elections after unexpected setbacks in the 2011 elections that saw United Russia’s share of the vote fall below 50% for the first time.

Moreover, nearly all of the remaining seats were awarded to opposition parties — like Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s Liberal Democratic Party (Политическая партия ЛДПР), Gennady Zyuganov’s Communist Party (Коммунистическая Партия) and Sergey Mironov’s A Just Russia (Справедливая Россия) — that long ago ceased to be anything but plaint, obedient and toothless in the face of Putin’s autocratic rule, whose party logos even mirror those of Putin’s United Russia party. Putin’s liberal opponents, operating under greater constraints than in past elections, failed to win even a single seat to the parliament.

The drab affair marked a sharp contrast with the 2011 parliamentary elections, the aftermath of which brought accusations of fraud and some of the most serious and widespread anti-government protests across Moscow (and Russia) since the end of the Cold War, prompting demands for greater accountability and democracy. Today, however, though Russia’s economy is flagging under international sanctions and depressed global oil and commodities prices, Putin’s power appears more absolute than ever. He’s expected to win the next presidential election with ease, thereby extending his rule through at least 2024 (when, conceivably, American voters could be choosing the successor to a two-term administration headed by either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump).

Moreover, more than 18 months after opposition figure Boris Nemtsov was murdered just footsteps from the Kremlin, perhaps the most telling statistic was the drop in turnout — from around 60% in the 2011 parliamentary elections to just under 48% this year. That’s the lowest in a decade, even as reports emerged of ballot-stuffing and other dirty tricks that may have artificially boosted support for Putin’s United Russia. Turnout in Moscow and St. Petersburg, where opposition voices have traditionally been loudest, fell even more precipitously to well below 30%. Though the low turnout might have boosted the share of support that Putin and his allies won, it’s also the clearest sign of growing disenchantment with Putin’s regime and its record on the economy (which contracted by nearly 4% last year, and is expected to contract further in 2016) and on civil and political rights. Corruption, as usual, remains rampant, even if oligarchs no longer dominate the Russian economy as they did in the 1990s.

Perhaps the most well-known opposition leader today, Alexei Navalny, a blogger who was at the heart of the 2011 protests, has been notably quiet (with his own ‘Progress Party’ banned from the election), though he is expected to contest the 2018 presidential vote — at least, if he’s not banned or imprisoned.

Notably, it was the first election since 2003 in which half (225) of the Duma’s seats were determined in single-member constituencies, with the other half determined by party-list proportional representation as in recent elections. Though United Russia won just 140 of the 225 proportional seats, it took 203 of the single-member constituency seats, which undoubtedly contributed to its 105-deputy gain on Sunday. One such new United Russia deputy is Vitaly Milonov, a St. Petersburg native who has battled against LGBT rights for years, including a fight to introduce a law in the local city parliament in St. Petersburg banning so-called ‘gay propaganda.’ (For what it’s worth, Russian authorities today censored one of the most popular gay news websites in the country).

For the Kremlin, though there’s some risk that the new constituency-elected deputies could be more independent-minded than party-list deputies, it’s a risk balanced by the massive supermajority that Putin now commands in the Duma.

Conceivably, as Moscow’s economic woes grow, there’s nothing to stop Putin and his allies from moving the scheduled presidential election to 2017 — and there are signs that Putin plans to do exactly that. (The weekend’s parliamentary elections were moved forward to September from an earlier plan to hold them in December, scrambling opposition efforts).

The elections came just a month after Putin replaced a longtime ally, Sergei Ivanov, as his chief of staff, a sign that the Kremlin is already looking beyond the next presidential race to what would be Putin’s fourth term in office (not counting the additional period from 2008 to 2012 when Putin’s trusted ally Dmitri Medvedev served as president, with Putin essentially running the country as prime minister).

For Putin, the flawed parliamentary vote also comes at a crucial time for Russia’s role in the international order. Increasingly at odds with NATO, Putin thumbed his nose at American and European officials when he annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014, then helped instigate a civil war in eastern Ukraine that continues even today. Increasingly, Putin believes that Russia has a geopolitical responsibility to all Russian-speaking people, even those outside Russia’s borders, complicating relations with several former Soviet states. Putin has also stepped up Russian military assistance to Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, providing crucial support against Sunni-dominated militias in Aleppo and elsewhere — even as Russian and U.S. officials try to extend a ceasefire in the country’s now five-year civil war.

Moreover, though the Russian parliamentary elections are hardly front-page international news, the results are relevant to the 2016 US presidential election, in which Russian influence and cyberattacks have played a prominent role. As Republican nominee Donald Trump continues to praise Putin as a ‘strong leader,’ it’s important to note that Putin’s strength comes in large part from a brutal disregard for the rule of law and the liberal and democratic values that have, for over two centuries, been a fundamental bedrock of American politics and governance. To the extent that the next president of the United States has to deal with Putin’s ‘strength,’ it will be derived in part from a parliamentary victory yesterday that bears no resemblance to the kind of democracy practiced in the United States today, but through a mix of authoritarian force and coercion. Continue reading Putin wins Russian parliamentary elections despite economic woes