It’s easy to forget that when Robert Mugabe first came to power in 1980, after a long guerrilla campaign against the white minority rule of Ian Smith in what was then still known as Rhodesia, life in Zimbabwe was optimistic. ![]()

A tale of post-colonial hell

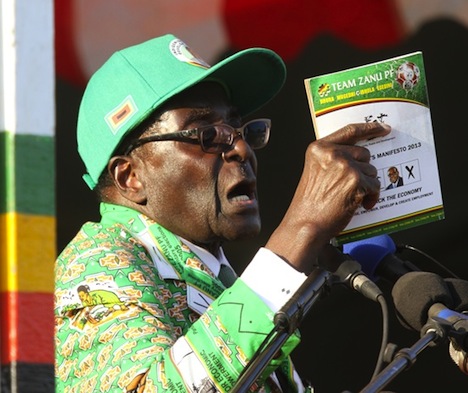

Despite his declarations that he wanted a one-party Marxist state as the more aggressive of three competing nationalist leaders, Mugabe (pictured above), the leader of the ZANU-PF (Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front) overwhelmingly won Zimbabwe’s first majority-rule election with just a hint of the political intimidation and violence that would be a harbinger of Mugabe’s rule to come. After the initial 1980 vote, with an air of magnanimity, Mugabe ushered in a post-independence era of optimism. He refused to harass the white minority of Zimbabwe, even retaining Ken Flower, Zimbabwe’s chief intelligence official, who had once been responsible for trying to assassinate Mugabe. More importantly for the black majority that could now express representative power in the country, Mugabe briskly set about enacting a program of improving education and health care for the masses, with promises of long-awaited land reform to come.

The honeymoon didn’t last long, and Mugabe turned first on his fellow nationalist rebels, the ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People’s Union), whose leader Joshua Nkomo initially served as secretary of home affairs in 1981 and 1982. Mugabe, who called Nkomo a ‘cobra in a house,’ turned on the ZAPU following a trumped-up scandal over alleged ZAPU arms caches, added that, like a cobra, Nkomo should be attacked and his head destroyed. Mugabe, who had been clandestinely constructing a secret ‘fifth brigade’ of soldiers loyal to Mugabe alone, began what would be a five-year campaign to subjugate the ZAPU. The fight took on the ugly shades of ethnic cleansing for the next five years, with the ZANU-PF and military brigades loyal to Mugabe, from the Shona ethnic group, largely harassing — and in some cases using a food embargo with the active goal of starving — the ZAPU supporters, largely based in southwestern Zimbabwe among the Ndebele ethnic group.

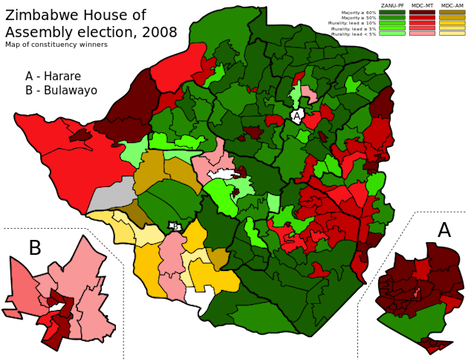

About 80% of Zimbabwe’s population of 12.75 million people today is Shona, an ethnic group that predominates throughout Zimbabwe and parts of southern Mozambique and that speaks Shona, a Bantu family language. But another 15% of the population belongs to the Ndebele ethnic group, which is clustered in the two provinces of Matabeleland, especially in the south (see below a province-level map of Zimbabwe’s 2008 results, which show Matabeleland, even two decades later, is an area of anti-Mugabe sentiment). Their northern Ndebele language is also a Bantu language, but belongs to the separate Nguni group of languages that also includes Zulu and Xhosa, the former nearly universally understood in South Africa and the latter an important minority language of about one-fifth of southeastern South Africa, and Swazi, spoken largely in Swaziland.

Notwithstanding the violence, residents in Matabeleland voted overwhelmingly for the ZAPU in the 1985 parliamentary elections, which led to ever more oppression. Nkomo essentially surrendered two years later, and Mugabe signed a unity agreement in 1987 that formally merged the ZAPU into the ZANU-PF and offered a general amnesty from an otherwise needlessly brutal effort to establish a one-party state.

In the meanwhile, the optimism with which a newly independent Zimbabwe launched had flagged. Mugabe had already begun his longstanding campaign against white settlers in Zimbabwe with threats of expropriation of land, and the economy had already started its long, slow retreat under the weight of Mugabe’s new social spending, the inefficiencies of state-run industry and the rampant corruption that increased with Mugabe’s patronage-based rule.

With the ZANU vanquished, Mugabe revised the constitution to eliminate the post of prime minister, consolidating its function into the head of state’s roles, and Mugabe easily won the 1990 presidential election with 83% of the vote, and the ZANU-PF won 117 out of 120 seats in what was then Zimbabwe’s unicameral parliament.

But the 1990s saw a further dip in the economy, especially after Mugabe accepted financial assistance from the World Bank that limited his ability to spend as freely as he had in his first decade in power, angering farmers and war veterans alike — the latter protested in the streets in 1997, demanding pensions for their previous service that Mugabe subsequently granted, though Zimbabwe’s treasury didn’t have enough money to fund them. Despite the institution of a more market-based economy, upon which World Bank assistance was contingent (the ‘structural adjustment program’), corruption accelerated in the 1990s as the economy’s deceleration continued apace, and though the lack of a true opposition meant that Mugabe’s ZANU-PF won 118 out of 120 seats in the National Assembly in 1995 and Mugabe was reelected with 92.75% of the vote a year later, conditions deteriorated in a way that not even Mugabe would be able to ignore.

The challenge ultimately came from within the ZANU-PF umbrella in the form of Morgan Tsvangirai, the leader of the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions, who was instrumental in calling strikes in 1997 and 1998 to protest increased taxes. Other Zimbabweans rioted against the increase in food prices as well as the extravagance of Zimbabwe’s military intervention in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to boost the regime of strongman Laurent Kabila.

A failed constitutional referendum, based as usual largely on the theme of land expropriation from white Zimbabwean farmers, in 2000 only led Mugabe to greater levels of intransigence and, of course, politically-motivated violence throughout Zimbabwe, including the most massive seizure of white-owned farmland to date. In the following June 2000 parliamentary elections, Tsvangirai’s newly formed Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) ultimately won 57 seats to just 63 for the ZANU-PF. Though the vote was flawed, it was the first sign that Zimbabweans were ready to consider moving on from Mugabe.

In the March 2002 presidential election, however, Mugabe deployed intimidation and fraud in equal measure, with the parliament’s passage of a media law that restricted press freedom just a month prior to the election. Despite the continued deterioration of the economy — the international community had ended what was left of their own aid programs and Zimbabwe faced huge shortages in all sorts of foods and goods — Mugabe won the March 2002 presidential election by an official tally of 56% to 42% for Tsvangirai. The European Union introduced sanctions against Zimbabwe in retribution and the Commonwealth suspended Zimbabwe indefinitely.

The ill-fated 2008 election and its aftermath

But the 2000s would bring even further bad news for Zimbabwe’s government. As Alex Thomson writes in a case-study on Zimbabwe in his magnificent An Introduction to African Politics, the statistics tell the tale of an economy in freefall:

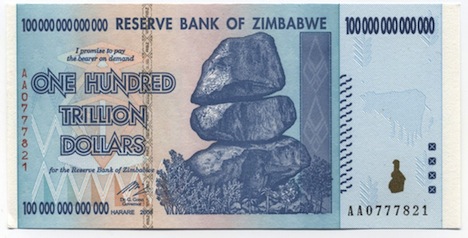

The national economy shrunk by one-third after 1999: average per-capita purchasing power returned to 1953 levels; 35 percent of the population lived below the poverty line in 1996, but this share grew to an estimated 80 percent by 2003; the commercial production of maize, the national staple, dropped 86 per cent between 2000 and 2005; and the volume of tobacco exports, once the country’s leading foreign exchange earner, fell by more than 60 per cent after 2000. Indicative of the scale of the economic collapse was that Zimbabwe, once a food exporter, the so-called ‘breadbasket’ of Southern Africa, became food insecure. More than one-third of the population became reliant on imported food aid. With inflation running at 500 billion per cent in 2008, and the Zimbabwe dollar becoming worthless, even those who has received land through the redistribution programme must have questioned ZANU-PF’s competence to rule.

If you think back to the dire days of Zimbabwe in 2007 and 2008, you’ll remember the examples of hyperinflation (sometimes so outrageous as to be borderline hilarious, if the human cost weren’t so tragic):

You’ll also remember the outbreak of cholera that began in August 2008 and continued throughout 2009, an epidemiological disaster that showed the ends of how an economic crisis becomes a humanitarian one, and that ultimately spread to Botswana and further throughout southern Africa.

Throughout all of this, the ZANU-PF managed (miraculously!) to increase its representation in the House of Assembly to 78 seats (with just 41 for the MDC), following a high-profile attempt to convict Tsvangirai for treason in 2004.

But as the country prepared for the March 2008 general election, when the president and the parliament (newly expanded from the House of Assembly to include a second, upper house, the Senate), Tsvangirai and much of what was now known as the MDC-T (the ‘T’ standing for Tsvangirai) were united against Mugabe. A smaller offshoot from the MDC, which broke with Tsvangirai over whether to boycott the 2005 election to the newly-formed Senate, today led by Welshman Ncube, competed in its own right during the election. The leadup to that election was characteristically marked by violence and intimidation, but the MDC-T emerged triumphant, and the MDC-T won 100 seats in the House of Assembly, to just 99 seats for ZANU-PF, with an additional 10 seats going to the variant MDC party:

In the Senate, ZANU-PF won 30 seats, MDC-T won 24 seats and the variant MDC won another six seats.

And in the all-important presidential vote, Tsvangirai bested Mugabe by a vote of 47.9% to 43.2% (though it would be nearly two months before the results were announced by Mugabe’s government).

With a runoff scheduled for June, Tsvangirai looked set to win the second round and end what then was the 27-year Mugabe rule. But as political violence escalated, and the number of election-related deaths crept into the hundreds and injuries crept into the thousands, Tsvangirai withdrew from the runoff one week before it was set to take place, allowing Mugabe to win uncontested.

Mugabe had little choice but to offer a power-sharing agreement with Tsvangirai, which was finalized in September of 2008. Tsvangirai was sworn in as Zimbabwe’s new prime minister in February 2009, a month after the country introduced the U.S. dollar and the South African rand as a more stable currency in a bid to end its hyperinflation, though he would be wounded — and his wife would be killed — in a car accident a month later that, according to all sources, was not politically influenced.

Since the power-sharing deal took effect, however, Zimbabwe has had an imperfect government between two groups, the MDC-T and the ZANU-PF, who despise and distrust one another, and accomplished little in the way of reform, though Tsvangirai was successful in lightening some EU restrictions on Zimbabwe. Over the past five years, Mugabe and Tsvangirai have spent more time disparaging the power-sharing agreement than effecting any real change in the country, though the two sides agreed on a new constitution that passed overwhelmingly in a March 2013 referendum and that would limit Zimbabwe’s president to two five-year terms (though Mugabe, if reelected today, would be entitled to serve up to 10 more years under a grandfather clause to the new constitutional term limits, when he’ll be 99 years old).

Today’s elections, which will choose Zimbabwe’s president, parliament and local officials, have been hastily scheduled in violation of the actual terms of the constitution agreed just four months ago. Though much of the international coverage has focused on the fight for the presidency, and the possibility that Mugabe could lose to current prime minister Morgan Tsvangirai, Zimbabwe’s voters will also choose members to the bicameral parliament, where no party currently holds an absolute majority.

So when we ask if today’s going to be the day that Mugabe is voted out of office, we’re really asking a handful of questions:

- The first is the simple question of whether a majority of Zimbabweans are prepared to vote Mugabe out of office.

- The second is whether a majority of Zimbabweans are ready to unite behind Tsvangirai.

- The third is whether the election will result in a parliamentary majority for the ZANU-PF or the MDC-T, and what might happen in the event of a Mugabe/MDC win or a Tsvangirai/ZANU win.

- The final — and perhaps the most important — question is whether the ZANU-PF, the military and security forces and Mugabe himself will actually give up power in the event that voters decide to remove him from office.

The answer to none of those questions is clear.

Mugabe’s rebound?

After nearly a decade of contraction, culminating in 2008, when Zimbabwe’s withered economy shrank by another 17.7%, the economy has returned to growth — 6% in 2010, 9.4% in 2011 and a somewhat more lackluster 5% in 2012, with an even more lackluster estimate of around 3% to 4% in 2013. Food shortages, so common in the late 2000s, have ended, and the siege mentality that afflicted Harare and the rest of the country at the time of the 2008 elections has mostly disappeared. At age 89, there’s a sense that Mugabe has recovered along with the economy.

Mugabe has championed the reintroduction of the Zimbabwe dollar as a top priority if reelected, but otherwise has not exactly put forward a progressive agenda that inspires confidence in the country’s future. But it’s nonetheless heavy on indigenous indignation, nationalization and the ‘siege mentality’ against the Western colonial powers, especially the United States and the United Kingdom, against which Mugabe has railed for decades to populist effect.

But since the presidential campaign is separate from the parliamentary campaign, there’s no guarantee that the ZANU-PF will deliver sufficient votes to secure Mugabe’s reelection — and that’s why, according to some sources, Mugabe has rebuilt a parallel electoral apparatus from within Zimbabwe’s military. With the ZANU-PF split between old-school hardliners and younger reformists, Mugabe’s decision to entrust his reelection to the military may well have been wise, which points to the likelihood of a split Mugabe presidential win and a MDC-T parliamentary win, though Tsvangirai has so far ruled out another power-sharing government.

Tsvangirai’s popularity

Tsvangirai (pictured above), age 61, must have known that any deal to enter into power with Mugabe would mean that his own credibility as an independent opposition would be tarnished, and there are strong indications that the shine of Tsvangirai’s appeal have worn off over five long years of bickering. The MDC-T, in the meanwhile, has been sullied with corruption charges of its own, and the tragically widowered Tsvangirai has been tied to a number of sex scandals by ZANU-PF in advertisements throughout the country. If Mugabe stands ready to take credit for the turnaround in Zimbabwe’s economy, Tsvangirai seems an easy target for the failures to achieve more through the power-sharing arrangement. Despite economic gains, Zimbabwe is certainly not a poster child for development, unemployment is running as high as 85%, and decaying education and health care programs remain in serious need of reform.

Then again, it’s hard to believe that the young urban base that has increasingly supported the MDC-T would turn back toward Mugabe, and the MDC-T held perhaps the largest opposition rally in Harare’s history just two days ago.

Though Tsvangirai has so far been unable to secure a ‘grand coalition’ among the opposition presidential candidates — Welshman Ncube, minister of industry and culture and the leader of the variant MDC faction, and Dumiso Dabengwa, who leads the remnants of the ZAPU movement, have so far failed to align behind Tsvangirai. That may, however, be irrelevant, as the campaign has been increasingly viewed as a two-man showdown.

Tsvangirai has campaigned on an agenda of encouraging foreign investment, in contrast to Mugabe’s push for ever-greater indigenous control.

A poll making the rounds in the past couple of days (though it was conducted at the end of March and early April) purports to show Tsvangirai with a massive lead of 61% to 27% for Mugabe, and that’s boosted expectations that Tsvangirai may finally take the presidency in his third attempt.

But if Tsvangirai, who has ruled out a power-sharing agreement with Mugabe after the election, can’t win on his third attempt, he may well be forced to recede and allow a new generation to have a go at Mugabe in 2018.

Free and fair elections at last?

On Tuesday, in front of the world’s media, Mugabe dismissed that Zimbabwe’s elections had been ‘rigged’ in the past, and he argued that the word ‘rigging’ itself was a foreign word. Furthermore, Mugabe pledged to step down if he loses to Tsvangirai, concisely noting, ‘If you lose, you must surrender.’ But there’s cause to be concerned about the process that led to today’s vote and how Mugabe might respond in the event that Zimbabwe’s voters eject him from office. U.S. officials have already criticized the lack of transparency ahead of today’s vote, up to four million expatriate Zimbabweans will not be eligible to vote, and Western observers have been barred from the election.

It’s true that there hasn’t been an incredible amount of violence in the lead-up to today’s election (though violence has been reported more frequently in the countryside where ZANU-PF is depending on its base for crucial support), but the fact that Mugabe is depending on the military to boost him to reelection, even more than the ZANU-PF party apparatus, is an indication of just how strong the security services have become over the past five years, and they allegedly hold a key stake in the diamond mining industry that, in part, has brought economic growth back to the country. As noted above, that militates in favor of a Mugabe win, no matter what he’ll need to do to shore up up his power, even if it means another five years of what the French so delightfully call cohabitation, a power-sharing deal with a parliament that could well be dominated by the MDC-T.

After all, it’s not without good reason that Mugabe has held onto power for 33 years — and, as in 2008 and before, Mugabe has shown that he’s perfectly willing to plunge his country into political, economic and social uncertainty to extend his grip on power.

Photo credit to Annie Mpalume.