While most of Europe was watching the birth of Germany’s latest grand coalition government last week, Austria’s grand coalition also finalized its government platform.![]()

Austria, which has an even stronger tradition of cozy coalition politics between the center-left and the center right, will continue to a coalition that’s comprised of its main center-left party, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ, Social Democratic Party of Austria) and its main center-right party, the Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP, Austrian People’s Party).

There was very little unexpected news about the coalition deal, which will continue the broadly centrist course of center-left chancellor Werner Faymann’s government.

But the decision to elevate the hunky 27-year-old Sebastian Kurz as Austria’s new foreign minister was something of a shock. Michael Spindelegger, the ÖVP leader and deputy chancellor, who previously served as foreign minister between 2008 and 2013, will become the government’s new finance minister.

The decision leaves Kurz (pictured above) as one of the world’s youngest political leaders in such a high policymaking role.

So who is this whiz kid? Kurz became involved in politics at age 10, and by 2009, he was the leader of the youth wing of the Austrian People’s Party. In 2010, he was elected to the city council of his native Vienna, running under the slogan, ‘Schwarz macht geil‘ (‘Black is cool,’ referring to the color most associated with the People’s Party) in a campaign Hummer that quickly gained the nickname as the ‘Geilomobil‘ (which translates roughly to ‘Horny-mobile’), befitting Kurz’s growing reputation as somewhat of a party animal. Before you judge him too harshly, however, remember that it was part of a wider push to make the ÖVP more attractive to young voters. And just four months ago, two competing leaders of the Austrian far right both posed shirtless in public.

But by 2011 he was already serving as state secretary for integration, where he impressed skeptics by working to ease the path for the growing number of immigrants to Austria, including through the institution of an extra year of pre-school for immigrant children to learn German. He helped spearhead a new immigration law in May of this year that clears a path to citizenship for some immigrants within six years.

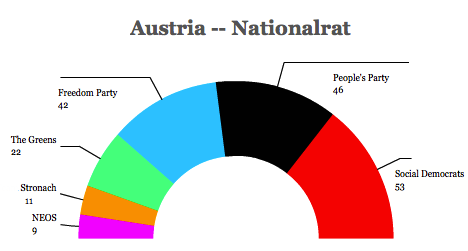

It was a controversial move on Spindelegger’s part, but it paid off, and Kurz was elected to the Nationalrat (National Council), the chief house of the Austrian parliament, in the September 29 parliamentary elections with a higher number of votes than any other candidate.

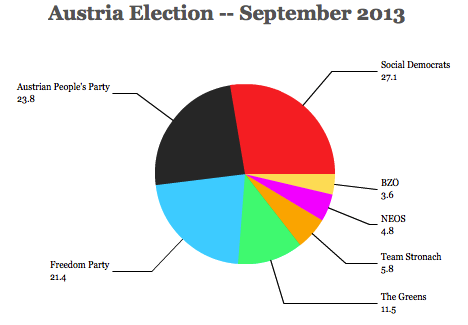

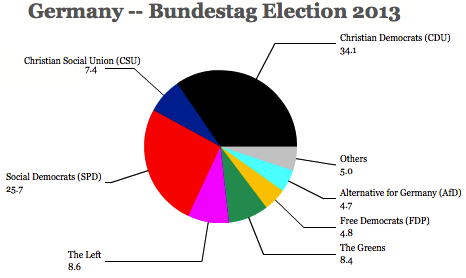

His approach contrasts with that of the more xenophobic approach to immigration of Austria’s far right. In September, the Social Democrats won 27.1% and the Austrian People’s Party won 23.8%, but the anti-immigrant, anti-EU Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ, the Freedom Party of Austria) won 21.4%, a strong third-place finish. But a Dec. 12 Hajek poll showed that if the elections were held over today, the Freedom Party would emerge as the leading party with 26%, followed by the Social Democrats with 23% and the Austrian People’s Party at 20%. A new free-market libertarian party, Das Neue Österreich (NEOS, The New Austria), which entered the National Council for the first time in September’s elections, would win 11%.

The Freedom Party’s relatively young and charismatic leader, Heinz-Christian Strache, wasted no time in criticizing Kurz for his inexperience:

“When Mr Kurz becomes foreign minister without any diplomatic experience, you have to be amazed. This is the continuation of Austria’s farewell to foreign policy,” right-wing leader Heinz Christian Strache told parliament on Tuesday.

Kurz… took the blows. “It’s true, of course. Due to my age I have limited experience and of course hardly any diplomatic experience. But what I bring is lots of diligence, energy and the desire to contribute something,” he told Reuters.

But Kurz emphasized the international nature of his previous role with respect to integration, and he argued that his relative youth and high media profile would allow him to make an immediate impact. Though Austria, with just 8.5 million people, has a less dominant voice on European matters than Germany, it plays a key role in the Balkans, where Serbia and other former Yugoslav countries are hoping to begin accession talks to the European Union early next year. (If your German skills are up for it, here’s an interview with Kurz in Der Standard earlier this week).

Kurz’s appointment also means that he will likely take a key role in the upcoming European Parliament elections by convincing Austrian voters not to turn to euroskeptic parties like the Freedom Party or Team Stronach, the conservative movement of Austro-Canadian businessman Frank Stronach. Spindelegger was criticized during his tenure at the ministry for being a ‘half-time foreign minister’ in light of his duties as the ÖVP leader and deputy chancellor. Continue reading Who is Sebastian Kurz? Meet Austria’s new 27-year-old foreign minister.