The theme of this week’s convention could have already been ‘I Took a Pill in Cleveland,’ because it’s clearly more Mike Posner than Richard Posner.![]()

![]()

All eyes last night were on Ted Cruz, the Texas senator who lost the Republican nomination to Donald Trump and, notably, Cruz’s pointed refusal to endorse his rival in a rousing address that is one of the most memorable convention speeches in recent memory. Trump’s allies instructed delegates to boo Cruz off the stage, and they spent the rest of the night trashing Cruz for failing to uphold a ‘pledge’ to support the eventual nominee.

But shortly after Cruz’s speech, David Sanger and Maggie Haberman of The New York Times published a new interview with Trump about foreign policy, in which he indicated that he would be willing as president to break a far more serious pledge — the mutual collective defense clause of Article Five of the North Atlantic Treaty that essentially undergirds the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the organization that has been responsible for collective trans-Atlantic security since 1949:

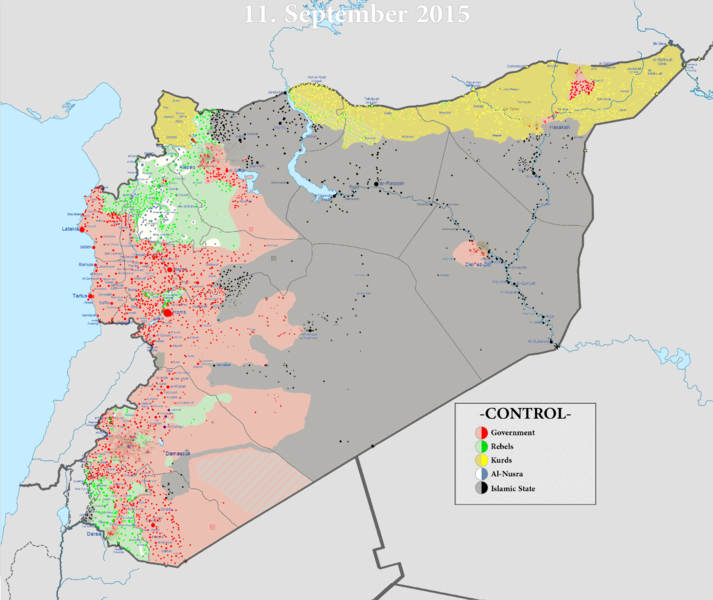

Asked about Russia’s threatening activities, which have unnerved the small Baltic States that are among the more recent entrants into NATO, Mr. Trump said that if Russia attacked them, he would decide whether to come to their aid only after reviewing if those nations “have fulfilled their obligations to us.”

“If they fulfill their obligations to us,” he added, “the answer is yes.”

Mr. Trump’s statement appeared to be the first time that a major candidate for president had suggested conditioning the United States’ defense of its major allies. It was consistent, however, with his previous threat to withdraw American forces from Europe and Asia if those allies fail to pay more for American protection.

The comments caused, with good reason, a foreign policy freakout on both sides of the Atlantic. The Atlantic‘s Jeffrey Goldberg wrote, ‘It’s Official: Hillary Clinton is Running Against Vladimir Putin.’ In The Financial Times, a plethora of European officials sounded off a ‘wave of alarm.’

In successive waves, NATO’s core members expanded from the United States and western Europe to Turkey in 1952, to (what was then) West Germany in 1955, Spain in 1982, the new eastern and central European Union states in 1999 and 2004 (which include three former Soviet republics, the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia), and Albania and Croatia in 2009. Of course, many of the more recent NATO member states spent the Cold War behind the Iron Curtain subject to Soviet dominance.

Above all, so much of eastern Europe joined NATO to protect themselves from Russian aggression in the future. Article Five provides that an attack on one NATO country is an attack on all NATO countries, entitling the NATO country under attack to invoke the support of all the other NATO members. This has happened exactly once in NATO’s decades-long history, when the United States invaded Afghanistan in the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks.

It’s not the first time Trump has slammed NATO during the campaign; he called it ‘obsolete’ in off-the-cuff remarks at a town hall meeting in March:

“Nato has to be changed or we have to do something. It has to be rejiggered or changed for the better,” he said in response to a question from an audience member. He said the alternative to an overhaul would be to start an entirely new organisation, though he offered no details on what that would be.

He also reiterated his concern that the US takes too much of the burden within NATO and on the world stage. “The United States cannot afford to be the policeman of the world, folks. We have to rebuild this country and we have to stop this stuff…we are always the first out,” he offered.

The latest attack on NATO and, implicitly, the international order since the end of World War II, came just days after NATO’s secretary-general, former Norwegian prime minister Jens Stoltenberg, announced a new plan for NATO cooperation on the international efforts to push back ISIS in eastern Syria and western Iraq. Stoltenberg, it’s worth noting, is the first NATO secretary-general to come from a country that shares a land border with mainland Russia. So he, more than anyone, understands the stakes involved. Continue reading NATO comments show why Trump could inadvertently start a global war