Everyone expects the Nobel Peace Prize to have a political meaning.![]()

![]()

![]()

By the very nature of the prize, it’s not surprising when the Oslo-based awarding committee makes a decision that is affected by — or that subsequently affects — international politics. That follows almost directly from the very words that Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel used to describe the prize’s qualifications:

The most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.

That was true earlier this morning, when Tunisia’s National Dialogue Quartet received the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize. The decision highlights Tunisia’s peaceful transition to democracy and the crucial role that the quarter played in late 2013 to salvage Tunisia’s fragile transition. With an economy that’s still struggling, Tunisia nevertheless remains the only Arab Spring country to depose its leader that is also still working to enshrine a democratic system of government. Libya, Syria and Yemen are locked in anarchy or civil war, and Egypt’s democratically elected president, Islamist Mohammed Morsi, was deposed in a 2013 coup by the Egyptian military. The award is a reminder that the Arab Spring really did bring forth some good in one of the most difficult regions of the world. As the awarding committee itself noted, the prize is essentially a nod to the Tunisian people themselves:

More than anything, the prize is intended as an encouragement to the Tunisian people, who despite major challenges have laid the groundwork for a national fraternity which the Committee hopes will serve as an example to be followed by other countries.

*****

RELATED: How Tunisia became the success story of the Arab Spring

*****

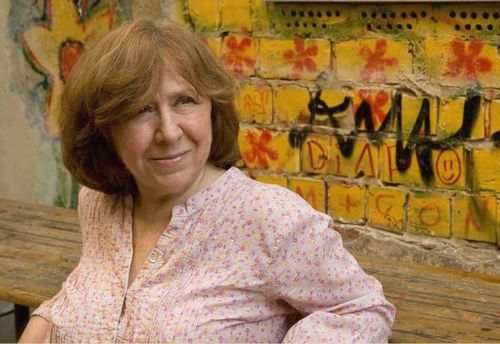

But it was arguably Thursday’s prize to Svetlana Alexievich for literature that makes the bolder and more timely political statement, even though it was awarded by the Swedish Academy (and not by the Norwegian Peace Prize selection committee).

The award would have been edgy enough solely because the Swedish Academy awarded the prize to a nonfiction writer and a journalist. As Philip Gourevitch wrote in The New Yorker in October 2014, the Prize has historically favored fiction over nonfiction, and most especially over contemporary journalism.

Literature prize a shot against Lukashenko — and Putin

But Alexievich’s award — for ‘her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time’ — came just three days before a sham election in Belarus.

Longtime post-Soviet president Aleksandr Lukashenko is seeking a fifth consecutive term in power, and his control over Belarus is nearly complete. Despite political protests in 2010 and 2011 that threatened to spiral out of control, Lukashenko redoubled his efforts to crack down on political dissent prior to the 2011 elections, and this year’s vote has not been greeted with similar protests. There’s no doubt he will win on Sunday. In no small measure, that’s due to his government’s efforts to crack down on opposition voices and press freedom in the leadup to the October 11 election:

The journalists take great precautions to elude detection, frequently moving their makeshift studio from one underground apartment to another, and transmit reports to Poland for broadcasting from there. Still they face regular searches and harassment.

In the run-up to Sunday’s presidential election, the government has gone after journalists like those at Belsat who seek to skirt state censorship by broadcasting from outside Belarus. So far this year, 28 journalists in the former Soviet republic have been slapped with hefty fines, in some cases after intimidating interrogation by the KGB.

Alexievich herself has dealt with the Lukashenko regime’s censorship directly, and she was forced to live abroad for a decade after harassment from Belorussian authorities. She returned to Minsk in 2011, however, and her writings have examined the Soviet Union’s painful war in Afghanistan, the role of women in World War II and the effects of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Belarus is currently suffering from the blowback of Russia’s economic crisis. A member of the Moscow-dominated Eurasian Economic Union, Lukashenko has traditionally been a reliable ally of Russia. But Russian incursions in Ukraine and Belarus’s weakening economy have highlighted the tensions between Minsk and Moscow. Russian president Vladimir Putin and Lukashenko reportedly do not have a great relationship, and that was true even before Russia’s aggressive move to annex Crimea from neighboring Ukraine and foment pro-Russia forces in eastern Ukraine, where a civil war continues even today.

Lukashenko won rare international praise for hosting two summits in late 2014 and early 2015 that attempted to bring peace to eastern Ukraine by assembling the key players, including Russian, Ukrainian, rebel and other European leaders, to Minsk. Though no one has particularly adhered to the Minsk accords, it showcased Lukashenko’s creeping interest in developing relationships with European countries and his growing role as a mediator between Moscow and Kiev. It was so impressive that the European Union seems to be set to lift economic sanctions on Belarus after the 2015 election, to the extent it deems that the Lukashenko regime does not crack down too intensely on opposition figures.

*****

RELATED: With Ukraine crisis,

Lukashenko between a rock and a hard place

*****

That’s hardly good news for independent writers like Alexievich, though her newfound exposure as a Nobel laureate might shield her from future persecution by the Lukashenko regime. The award, too, highlights the perilous conditions that independent journalists face, not only in Belarus, but throughout the post-Soviet world. Anna Politkovskaya, the famous Russian journalist assassinated on her own doorstep in 2006, is just one of dozens of Russian journalists killed in the Putin era. Reporters without Borders, in its annual World Press Freedom Index, ranks Russia 152nd worldwide for press freedom, and Belarus is even worse, ranked at 157. At a time when Russia is seeking out greater adventures on the world stage, from Ukraine to Syria, it’s arguably more important than ever that independent voices can report what’s happening on the ground. Recognizing Alexievich, her work and her courage as a journalist was a timely and crucial nod for press freedom.

Tunisia’s success story belongs to everyone, not just the quartet

That’s not to say that the Tunisian quartet isn’t worth of the Peace Prize. Far from it, It’s arguably a much more germane choice than, Pope Francis I, who already benefits from a global spotlight and a generally fawning international press. Though it would have arguably been an even more timely award in 2013 or 2014, the 2015 Peace Prize will shine a spotlight on a country that long ago fell from front-page headline status, even as the hard grind of building democracy and the rule of law will continue for years and even decades to come.

The quartet pulls together four organizations, including the Union Tunisienne de l’Industrie du Commerce et de l’Artisanat (UTICA,Tunisian Confederation of Industry, Trade and Handicrafts), La Ligue Tunisienne pour la Défense des Droits de l’Homme (LTDH, Tunisian Human Rights League) and the Ordre National des Avocats de Tunisie (ONAT, Tunisian Order of Lawyers).

But it’s arguably the strength of the Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail (UGTT, Tunisian General Labour Union) that mattered most to putting Tunisia back on the track to functional democracy. Formed in 1946 and one of the truly influential elements of civil society through both the Bourguiba and Ben Ali regimes, the UGTT’s dues-paying members included around 5% of the national population at one point during the 2013 political crisis. Its general-secretary Hassine Abassi was instrumental in pushing through the road map that resulted in the 2014 general election.

Above all, though they weren’t part of today’s award, it’s worth recognizing the moderation of Tunisia’s Islamist party, the Ennahda Movement (حركة النهضة, Arabic for ‘Renaissance’). Rashid al-Ghannushi, its leader, agreed that the part would step down from running the Tunisian constituent assembly that had reached an impasse in writing the country’s new constitution. By handing over the process to a technocratic government, Ennahda showed that it was willing to put Tunisia’s transition above petty politics.

Equally important, Ennahda declined to nominate a candidate for the Tunisian presidency, and the party gracefully admitted defeat in last October’s parliamentary elections. At every step of the Tunisian experiment in democratization, Ennahda has been careful not to repeat the mistakes and overreach that characterized Morsi’s year in office and the Muslim Brotherhood’s approach to governance in Egypt. Even though the secular Nidaa Tounes (حركة نداء تونس, Call of Tunisia) and the 88-year-old president Beji Caid Essebsi now rule Tunisia, Ennahda is operating more or less as a loyal opposition. Above all, statesmen like Essebsi and Ghannushi should take as much pride in today’s Nobel Peace Prize as any of the other members of the quartet.