Before the Kevin and Julia show, there was the Tony and Malcolm show.

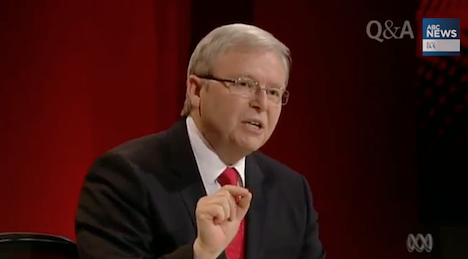

The rivalry between the dueling camps of Labor prime minister Kevin Rudd and former Labor prime minister Julia Gillard is now legendary — Rudd came to power in November 2007 after waging a near-perfect campaign (‘Kevin 07’) that brought the Australian Labor Party back to power after over a decade in opposition. But his deputy prime minister Julia Gillard became prime minister in June 2010 after Rudd’s parliamentary colleagues wearied of his leadership style. Gillard led Labor to the narrowest of reelections in August 2010 in what remains a hung parliament. Rudd, who returned to government as Gillard’s foreign minister shortly after the election, challenged Gillard for the Labor leadership in February 2012 — and lost. But as Gillard’s poll standing deteriorated throughout 2013, Rudd’s supporters engineered another vote in June 2013, and so Rudd (not Gillard) is leading Labor into Australia’s election on Saturday.

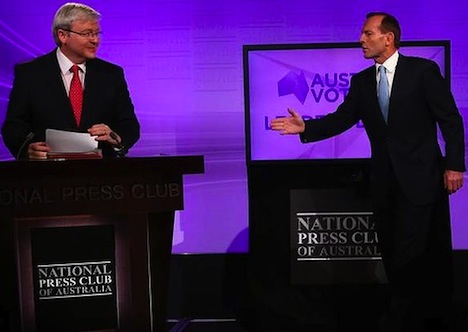

What’s less well-known is that opposition leader Tony Abbott (pictured above) emerged as the leader of the Liberal Party (and the center-right Liberal/National Coalition) after engineering a leadership spill of his own in December 2009. After former prime minister John Howard lost his seat in the 2007 election, the Liberals turned initially to Brendan Nelson, but finally to Malcolm Turnbull as its leader in 2008. But when Turnbull pushed his party to support the Labor government’s carbon reduction scheme, Abbott challenged Turnbull and improbably won a 42-41 victory on the second ballot, giving the Liberals their fourth leader in three years.

It’s an understatement to say that Abbott has proven a hard sell to the Australian public — in some ways, Abbott is akin to the Barry Goldwater or even the Ronald Reagan of Australian governance, a conviction politician and a conservative’s conservative who will undoubtedly pull Australia to the right.

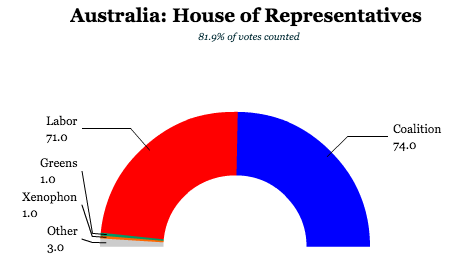

A staunch Catholic who once studied in seminary for a career in the church (nicknamed early in his career by the press as the ‘Mad Monk’), a boxer with plenty of appetite for aggression in Australia’s House of Representatives, and a conservative who once studied at Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship, Abbott is multifaceted and talented. But there’s no doubt that he’s socially and economically more conservative than Turnbull, Howard or Malcolm Fraser (prime minister from 1975 to 1983). Abbott also had more ties to the recently rejected Howard government than Turnbull, having served as employment minister from 1998 to 2003 and health minister from 2003 to 2007. Australian voters remained too hesitant about Abbott to hand the government back to the Coalition in 2010, but just barely. Today, the Coalition holds one more (72 to 71) seat than Labor in the House of Representatives, but independents and the Australian Greens have provided the Gillard/Rudd government a 76-74 majority since 2010. It’s a similar story in the Senate, where the Coalition already holds a 74 to 71 advantage over Labor, which governs with the support of nine Green senators.

Just as Rudd routinely garnered higher approval ratings than Gillard between 2010 and 2013, Turnbull posted higher ratings as well. Commentators in early 2013 daydreamed over the possibility that both of Australia’s major parties would dump their unpopular leaders in favor of their more charismatic alternatives.

But while Rudd and Gillard plotted and schemed over leadership, dragging Labor’s government and Australia into what amounted to a personality contest, Turnbull refrained from challenging Abbott for the Liberal leadership. The difference between the Labor approach and the Liberal approach is one reason why Abbott is a certain favorite to become Australia’s next prime minister.

Since returning as prime minister in June, Rudd has spent most of his time flailing — although a Newspoll survey showed Rudd’s Labor tied with Abbott’s Coalition as recently as July 8, Labor now trails the Coalition in the two-party preferred vote (i.e., after all third-party voter preferences have been distributed to Labor and the Coalition) by a 54% to 46% margin, according to the latest September 1 Newspoll survey.

But Rudd’s campaign has managed to do what even Gillard’s government could not — turn Abbott into a plausible prime minister. For the first time in the campaign, more voters prefer Abbott as prime minister (43%) than prefer Rudd as prime minister (41%) — that’s an astounding turnaround, given that an early August poll showed that voters widely preferred Rudd to Abbott by a 47% to 33% margin. Ironically, though Rudd was supposed to be Labor’s secret weapon in winning a third term in power, Abbott has so completely transformed his image through the course of the campaign that Rudd may now be saddled with the kind of landslide defeat that terrorized his Labor colleagues into sacking Gillard just three months ago.

If Abbott delivers the kind of victory that polls predict on Saturday, it will be in large part due to the self-destructive factional battles within Labor, but it will also have much to do with Abbott’s steady happy-warrior approach over the past four years.

So what will Abbott’s likely win mean for Australia as a matter of policy, beyond the presumable end to the instability of the Rudd-Gillard era?

Here’s a look at seven issues to keep an eye on in what’s become an increasingly likely Abbott government. Continue reading What should Australia expect from prime minister Tony Abbott? →

![]()