With prime minister Stephen Harper’s decision to call an election last week, Canada has now launched into a 13-week campaign that ends on October 19, when voters will elect all 338 members of the House of Commons, the lower house of the Canadian parliament.

By American standards, where Republican presidential candidates will gather for their first debate nearly six months before a single vote is cast (for the nomination contest, let alone the general election) a 13-week campaign is mercifully short. In Canada, however, it’s twice as long as the most recent campaigns and, indeed, longer than any official election campaign since the late 1800s. But the major party leaders have already engaged in one debate — on August 6.

Plenty of Harper’s critics suggest the long campaign is due to the fundraising advantage of his center-right Conservative Party. Harper, who came to power with minority governments after the 2006 and 2008 elections and who finally won a majority government in 2011, is vying for a fourth consecutive term. He’ll do so as the global decline in oil prices and slowing Chinese demand take their toll on the Canadian economy, which contracted (narrowly) for each of the last five months.

Energy policy and the future of various pipeline projects (such as Energy East, Kinder Morgan, Northern Gateway and the more well-known Keystone XL) will be top issues in British Columbia and Alberta. Economic growth and a new provincial pension program will be more important in Ontario. Sovereignty and independence will, as usual, play a role in Québec — though not, perhaps, as much as in recent years.

In reality, the battle lines of the current election have been being drawn since April 2013, when the struggling center-left Liberal Party, thrust into third place in the 2011 elections, chose Justin Trudeau — the son of former Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau of the 1970s and 1980s — as its fifth leader in a decade. Trudeau’s selection immediately pulled the Liberals back into first place in polls, as Liberals believed his pedigree, energy and sometimes bold positions (Trudeau backs the full legalization of marijuana use, for example) would restore their electoral fortunes.

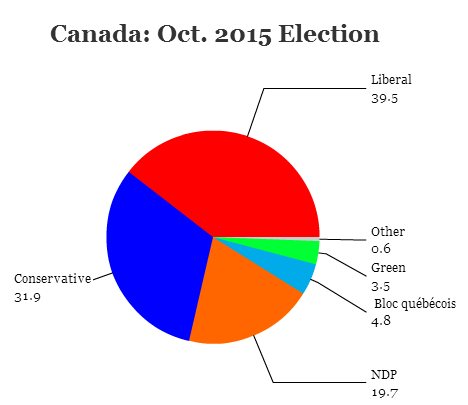

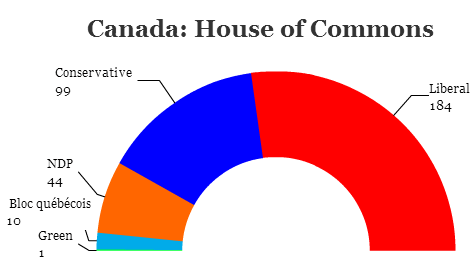

Nevertheless, polls suggest* that two years of sniping from Harper about Trudeau’s youth and inexperience have taken their toll. The race today is a three-way tie and, since the late spring, it’s the progressive New Democratic Party (NDP) that now claims the highest support, boosted from the NDP’s landslide upset in Alberta’s May provincial election. (*Éric Grenier, the self-styled Nate Silver of Canadian numbers-crunching, is running the CBC poll tracker in the 2015 election, but his ThreeHundredEight is an indispensable resource).

With the addition of 30 new ridings (raising the number of MPs in Ottawa from 308 to 338) and with the three parties so close in national polls, it’s hard to predict whether Canada will wake up on October 20 with another Tory government or a Liberal or NDP government. If no party wins a clear majority, Canada has far more experience with minority governments than with European-style coalition politics, and the Liberals and NDP have long resisted the temptation to unite.

Canadian government feels more British than American, in large part because its break with Great Britain was due more to evolution than revolution. Nevertheless, political campaigns have become more presidential-style in recent years, and the latest iteration of the Conservative Party (merged into existence in 2003) is imbued with a much more social conservative ethos than the older Progressive Conservative Party. The fact that polls are currently led by a left-of-center third party, the New Democratic Party (NDP), also demonstrates that the Canadian electorate, which benefits from a single-payer health care system, is willing to shift more leftward than typical American electorates.

Provincial politics do not often portend changes in federal politics, but the 2015 election is proving to be influenced by political developments in Alberta, Ontario, Québec, Manitoba and elsewhere, and many provincial leaders have not been shy about voicing their opinions about federal developments — most notably Ontario’s Liberal premier Kathleen Wynne.

Continue reading In Depth: Canada’s general election →

![]()