Financial reporter David Wessel provides a hilarious anecdote about Ben Bernanke, currently the chair of the Federal Reserve, from his days on the Bush administration’s economic team in his 2009 book, In FED We Trust: Ben Bernanke’s War on the Great Panic, that captures in capsule form one of the reasons why Bernanke has made such a great Fed chair:

One day, Bernanke showed up for a monthly Oval Office meeting wearing a dark blue suit and light tan socks.

Bush notices. ‘Ben,’ the president said, according to one participant, ‘where did you get those socks?’

‘Gap,’ replied Bernanke. ‘Three pair for seven dollars.’

The president wouldn’t let it go, mentioning Bernanke’s light tan socks repeatedly during the forty-five-minute meeting.

At the next month’s meeting, Bernanke had convinced nearly the entire staff, as well as U.S. vice president Dick Cheney, to wear tan socks, getting the last laugh on Bush. Beyond the innocent prank, the implication is clear enough — Bernanke, always a bit of an outsider in Washington, was wearing tan socks in a city of black socks. That’s perhaps appropriate for a Jewish economist who grew up in South Carolina.

That distance has been one of the understated keys to Bernanke’s success as Fed chair since 2006 — he’s a rare Fed chair who has enough distance from official Washington to be a credibly independent central banker but also sufficient experience to navigate Washington’s politics. Despite his eight-month stint as chair of the Bush administration’s Council of Economic Advisers, Bernanke had also chaired Princeton University’s economics department for six years and served as a member of the Fed’s seven-person Board of Governors from 2002 to 2005. He’s not the kind of Washington fixture that Alan Greenspan had increasingly become in his 19 years as Fed chair, nor is Bernanke’s wife a consummate political insider like NBC correspondent Andrea Mitchell, Greenspan’s wife.

As Felix Salmon writes today at Reuters, the Fed chair is one of the two most important officers in the United States. Bernanke’s successor, who will take office in February 2014, will be even more important to world politics, in at least an indirect capacity for his role in global markets, than U.S. secretary of state John Kerry, U.S. treasury secretary Jacob Lew or U.S. defense secretary Chuck Hagel.

Right now, there are two frontrunners:

- Lawrence Summers, treasury secretary in the Clinton administration from 1999 to 2001, Harvard University president from 2001 to 2006 and the hard-charging director of the Obama administration’s National Economic Council from 2009 to 2010; and

- Janet Yellen, vice chair of the Federal Reserve since 2010, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco from 2004 to 2010, and the chair of the Clinton administration’s Council of Economic Advisers from 1997 to 1999.

The conventional wisdom is that Summers has an edge, because Obama knows him so well, and trusts him, on the basis of his role earlier in the administration. So Obama therefore prefers to appoint Summers, as do all of the top economic policymakers close to Obama, such as Lew, former treasury secretary Timothy Geithner and current NEC director Gene Sperling.

The conventional wisdom is also that while Summers is a exceedingly brilliant and talented economist, he is not someone who values collaboration, a key trait for someone whose goal is to lead the 12-member Federal Open Market Committee that is comprised of the seven members of the Board of Governors and a rotating slate of five of the 12 regional Federal Bank presidents. The substantive knocks on Summers are even greater. He supported deregulation within the financial industry during the Clinton administration that allowed for the proliferation of new financial derivatives markets, and he opposed the ‘Volcker Rule’ in the 2010 Dodd-Frank package of financial reforms that restricts banks from using deposits in riskier trading. That’s not counting his controversial turn at Harvard, when he was forced to resign over comments suggesting that men have a greater natural aptitude for the sciences nor does it take into account the conflicts of his post-government employment with private-sector Wall Street firms like Citigroup and hedge fund D.E. Shaw or his lack of actual experience within the Federal Reserve system.

Tyler Cowen at Marginal Revolution argues that Summers is preferable to Yellen because Summers has more ‘right-wing street cred,’ and therefore might work more easily with the current Republican-controlled U.S. House of Representatives and a potential future Republican presidential administration, both because he’s taken more criticism from the left than Yellen and because of Yellen’s background at Berkeley.

But Salmon argues that Yellen would be a better chair on the day-to-day matters that are crucial to stabilizing the U.S. and global economy (noting that any Fed chair would respond to a financial crisis guns-a-blazin’). Ezra Klein, at The Washington Post‘s Wonkblog, argues that we don’t know which candidate would be stronger on financial regulation, another key Fed role. Paul Krugman argues that Yellen’s detractors are motivated by rampant sexism:

Sorry, but it’s hard to escape the conclusion that gravitas, in this context, mainly means possessing a Y chromosome.

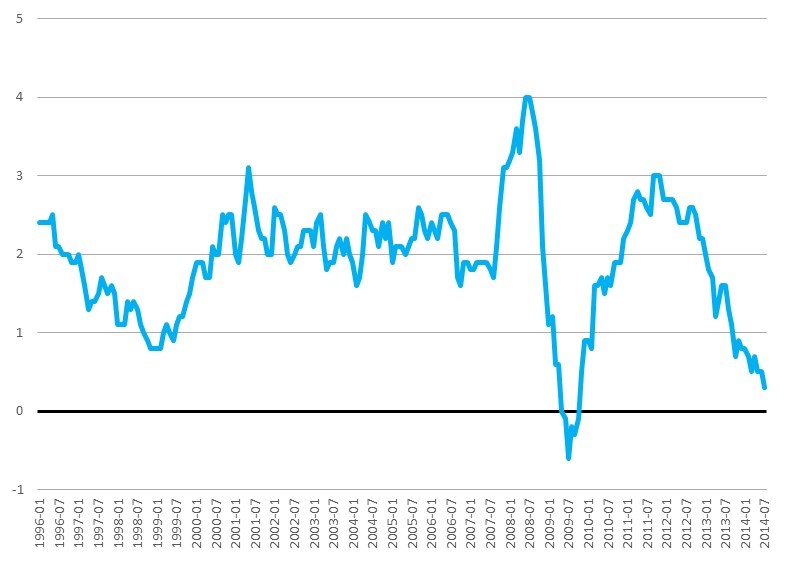

In the grand scheme of things, both Yellen and Summers are likely to pursue similar policies. Even though Yellen has been labeled an inflation ‘dove,’ there’s no indication that either Yellen or Summers will abandon Bernanke’s January 2012 decision to set an explicit 2% inflation rate target for the first time in Fed history. But the next Fed chair will most certainly wind down the Fed’s extraordinary ‘quantitative easing’ actions of the past five years whereby the Fed has purchased assets, bonds and other securities at an unprecedented rate, thereby boosting liquidity in the global financial system.

The reason to appoint Yellen is not because she is a woman, because she’s an inflationary ‘dove,’ because we think she might be a stronger advocate of financial regulation or even because she has more experience within the Fed. It’s because she will be seen to have more independence at a time when central bank independence will be crucial to the Fed’s success — that makes Yellen the ‘tan socks’ candidate for Fed chair, and it’s the key reason why Yellen’s nomination should be a slam-dunk case for Obama. Continue reading Yellen is the ‘tan socks’ candidate for Fed chair — and that’s why Obama should pick her →

![]()

![]()

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much

Draghi stressed that he understands the biggest risk to European Union’s economic recovery is deflation. He noted that the ECB is transitioning from a more passive approach to a much