When Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三) returned to power in December 2012 in a landslide victory, he did so with a platform of fiscal stimulus that makes previously profligate governments of the long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō) seem like budget hawks.

What a difference three years in opposition makes.

Abe previously served as prime minister from 2006 to 2007, a term most distinguished for Abe’s nationalist rhetoric with respect to the People’s Republic of China. Although the LDP has never been terribly allergic to public works projects, Abe returned to office with a campaign pledge to use government as a tool to spur the Japanese economy in a way that no Japanese government has contemplated since low-growth malaise took hold in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Audacious doesn’t begin to describe what’s already become known as ‘Abenomics,’ and with a two-thirds majority in the lower house of Japan’s Diet, Abe has already embarked on a program of ¥12 trillion ($136 billion) in spending on public works and other stimulative measures designed to be a down payment on up to ¥200 trillion in spending over the next decade. That’s even more striking in contrast to the prior government controlled by the now-decimated opposition, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō). DPJ prime minister Yoshihiko Noda (野田 佳彦) spent much of his time in office passing an increase in Japan’s consumption tax from 5% to 10%, which should take effect starting in 2014, though all bets are off if the LDP wins a rout in this summer’s elections to the Diet’s upper chamber, the House of Councillors.

But the truly radical step has been Abe’s willingness to advance a vision of monetary policy that, until now, has been advanced only by the likes of Paul Krugman and other folks with views less orthodox than your average central banker.

During the campaign, Abe blatantly called on the Bank of Japan to raise its inflation target to 2% or even 3% after years of deflation, and he pledged to force the Bank of Japan to purchase construction bonds from the Japanese government, making it clear that he is willing to intrude on the traditional independence of Japan’s central bank.

Last year, it was seen as a radical step when Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke set an explicit U.S. inflation target of 2% for the first time in a century of U.S. central banking history.

With the term of BoJ governor Masaaki Shirakawa (白川 方明) ending in April 2013, Abe was always certain to get his way on monetary policy. With Shirakawa’s early exit, however, Abe has gotten a head-start in nominating Harhuiko Kuroda (黒田 東彦), currently the head of the Asian Development Bank, as the next BoJ governor.

Kuroda (pictured above) has been the president of the Asian Development Bank since February 2005, and he previously served as a vice minister of finance for international affairs from 1999 to 2003 and as a special adviser to the LDP’s reformist former prime minister Junichiro Koizumi (小泉 純一郎). He will take over at a time when interest rates have been at zero for years, and deflation has been a problem for Japan for so long that investors expect structural deflation.

Gavyn Davies at FT Alphaville speculated earlier this week prior to the nomination that Kuroda is both pragmatic enough to win confirmation and audacious enough to pursue an aggressive easing campaign:

[He] has been very critical of the BoJ’s failure to eliminate deflation, and has strongly supported aggressive balance sheet expansion, and forward policy guidance, to achieve a 2 per cent inflation target. He has not, however, argued in favour of BoJ purchases of foreign bonds, which is one of the litmus tests being used by investors to gauge the attitude of the new incumbent…. Mr. Kuroda might be seen as a compromise candidate who could win the support of the Upper House of the Diet, a chamber which Mr. Abe does not control.

There are about a half-dozen bank governors who really, truly matter in terms of establishing what’s considered mainstream global monetary policy — and Kuroda will likely now be one of them, joining Bernanke, European Central Bank president Mario Draghi, Swiss National Bank president Thomas Jordan, and Canadian central bank governor Mark Carney, who is set to replace Mervyn King as the Bank of England governor in July 2013.

Kuroda’s appointment is important not only to Japan, obviously, but to the world in at least two ways.

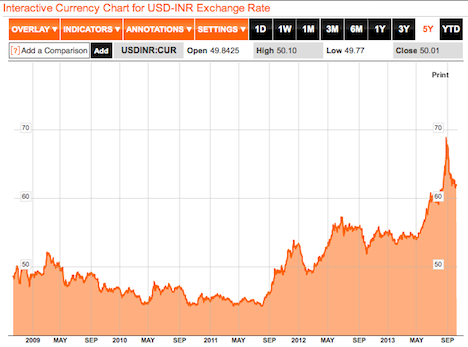

First, monetary policy in the Abe-Kuroda era will have a ripple effect on the global economy — after all, Japan does have the world’s fourth-largest economy with a GDP of around $4.6 trillion, just about 30% of the size of the entire U.S. economy. Markets, in fact, are already moving in anticipation of expected monetary easing — the value of the Japanese yen has dropped about 20% since last October, and the value of Japanese stocks has risen by 28%. It goes without saying that if Abe can spur the Japanese economy out of deflation and into a phase of higher growth, with greater Japanese consumption, it would boost the global economy, as well as the U.S. economy.

Second, to the extent Kuroda succeeds in his experiment, it will provide a more ambitious central banking precedent that could pull monetary policy worldwide to a more relaxed view about inflation.

But the strategy isn’t without potential pitfalls. Continue reading Who is Haruhiko Kuroda? →

![]()