Photo credit to Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty.

Photo credit to Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty.

In Japanese politics, few figures loom larger than Ichirō Ozawa (小沢 一郎), who has been a MP in Japan’s parliament since 1969.![]()

On Sunday, he faced the largest challenge of his political career, when as the leader of the People’s Life Party (生活の党, Seikatsu no Tō), he struggled to hold onto his own constituency in northern Iwate prefecture, campaigning in his home city of Ōshū for the first time in three decades.

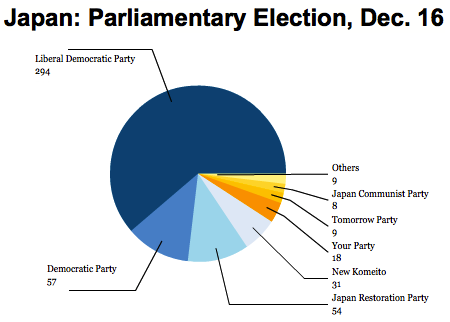

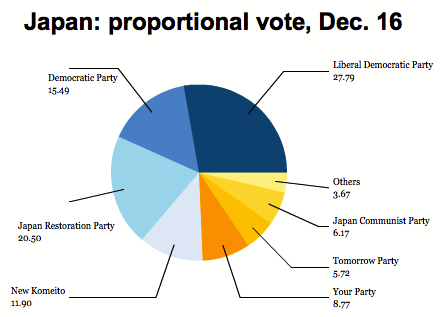

As it turns out, Ozawa (pictured above) held off his opponent by more than 10 points, winning one of just two seats for the People’s Life Party. So while Ozawa will return to the House of Representatives, the lower house of Japan’s parliament, the Diet (国会), he will do so as an increasingly isolated relic after reaching the pinnacle of leadership in both the dominant Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō) of prime minister Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三) and the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō), which held power for three tumultuous years from 2009 to 2012.

* * * * *

RELATED: Japan is once again an essentially one-party country

* * * * *

Known for decades as Japan’s ‘shadow shogun’ for the power he wielded behind closed doors, it’s no exaggeration to say that Ozawa is one of the leading figures of postwar Japanese politics. He was a vital figure in the LDP’s 1980s dominance, and he was instrumental in leading the only two movements that have dislodged the LDP’s six-decade political hegemony. In 45 years of political life, Ozawa himself has gone from conservative to liberal and back again with no clear ideological compass beyond gaining (and regaining) power. Although he’s a controversial figure, there’s no doubting that he has played a greater role than nearly anyone else in Japan in the effort to create a truly multi-party system, even while he’s disparaged Christianity as an exclusionary religion, claimed to ‘hate’ Europe and once derided Americans as ‘mono cellular’ and ‘simple-minded.’

At age 72, and leading a caucus that contains just one other legislator, few would disregard Ozawa’s ability to mount yet another comeback, especially if Abe’s efforts to stimulate Japan’s economy, once again tumbling into recession, ultimately fail. That’s especially true with few credible opposition figures in sight. Continue reading Ozawa, Japan’s one-time ‘shadow shogun,’ survives wipeout