Raghuram Rajan, the new governor of the Reserve Bank of India, is in Washington this week for World Bank and International Monetary Fund meetings, and he spoke briefly at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies earlier today, sharing some thoughts about India’s economy — where it’s at today and where it’s going tomorrow. ![]()

Most striking, perhaps, was Rajan’s bullishness that India’s economy has already bottomed out at around 4.4% GDP growth during the summer.

While 4% would be blockbuster growth in the United States or in Europe, it amounts to a drastic slowdown for a country that experienced an economic boom for much of the past decade, peaking at 10.5% GDP growth in 2010. Rajan blamed the usual suspects — India’s poor infrastructure, inadequate human capital development and overregulation during the ‘go-go years,’ but he predicted GDP growth would pick up next year. He also noted that prime minister Manmohan Singh’s current government (a government he advised before his appointment as India’s new all-star central bank governor) has taken appropriate steps over the past year, including liberalizing India’s retail sector, that will put India on a course to return to higher growth in the years ahead.

Here’s what he had to say about some of the other economic issues that he’ll face in the months and years ahead as RBI governor.

India’s current account deficit. Rajan was fairly sanguine about India’s current account balance, which spiraled from a 2% surplus just a few years ago to a nearly 4% deficit today. Rajan blamed the prices of four imports in particular– oil, gold, coal and iron ore. Although India produces about 900,000 barrels of oil a day, that’s just 1% of global production, and India heavily depends on oil imports. While coal and iron ore are abundant, Rajan said that India hasn’t mined enough of either resource because of problems with royalties, environmental concerns, property rights and legal consents. He was hopeful that many of those problems have now been fixed, and that India is set to mine more in the future.

But the largest component, by far, of the current account deficit has been gold imports, and Rajan said that the Indian government’s measures to reduce gold imports (i.e., raising tariffs from 4% to 6%) in the short-term have been successful. One of the drivers of rising demand for gold is the lack of access to banking for millions of rural and poor Indians, and long-term efforts to promulgate wider banking services falls directly within Rajan’s regulatory scope as RBI governor (of course, it’s difficult to slap a tariff on bitcoin).

Banking (and other) infrastructure. Rajan tried to assure that India’s shaky power infrastructure is on the right path, with new power plants coming online to address the country’s growing demand for more energy. He also extolled the Mumbai-Delhi industrial corridor, with its promise of high-speed freight rail, a new six-lane highway, and massive development in the swath of India linking the two megacities.

But it was heartening to hear Rajan talk about transforming India’s financial system as well — he was enthusiastic about issuing new bank licenses, and he pointed to Indian banking innovations like ATMs for the illiterate. While we don’t normally think of banking services as a vital good in the same way as, say, clean water or a stable source of affordable food, access to banking services is a vital element in lifting millions of Indians out of poverty — instead of hoarding rupees (or gold!) at home, greater banking would provide all Indians the reliability of safe savings, deposits and withdrawals.

Fed tapering and the rupee. It’s been clear for some time that the US Federal Reserve’s extraordinary measures to pump liquidity into global financial markets has greatly impacted emerging markets, including India, and it’s arguable that the Fed engendered a bubble in emerging markets over the past five years. That boosted the value of many emerging market currencies, including the rupee, and stoked growth in emerging market countries as investors sought returns that were difficult to find in the United States, especially in a world of zero-bound interest rates. When Fed officials started talking openly about ‘tapering’ off its quantitative easing programs, the rupee’s value dropped along with those same emerging market economies.

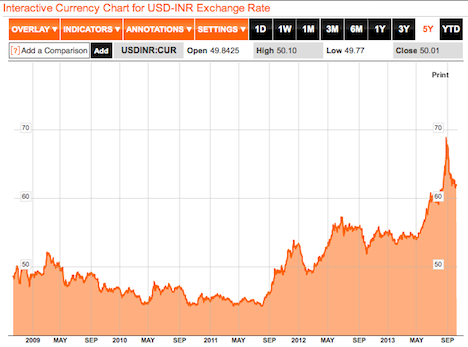

Indian officials are hopeful that the rupee has reached a floor at around 60 to 65 rupees to the US dollar, but if you look at the value of the rupee against the US dollar over the past five years, there’s still quite a bit of room for the rupee’s value to drop further — and the latest plateau in the rupee’s fall may have more to do with the fact that Fed chair Ben Bernanke made clear last month that it’s not yet time to start ‘tapering’:

While Rajan may be one of the sharpest minds in global finance, his hands as RBI governor are tied in the face of the stronger forces of the Fed’s actions. He was hopeful, however, that the Fed’s delay in tapering will give India more time to post a couple of quarters of stronger GDP growth and some adjustments in the current account deficit, thereby steeling the rupee against those forces when tapering really kicks in.

India’s public debt. Rajan wasn’t incredibly concerned about Indian public debt (around 66% of annual GDP), especially given its relatively small level of external debt (around 22%), and he said that India is having no trouble with external financing. There’s still so much growth potential in India that it’s reasonable to conclude its public debt isn’t much to worry about; while the rate of India’s population growth is slowing, the total population is still growing — unlike, say, Russia or Japan or much of Europe. Moreover, Rajan noted that the Indian government’s future welfare obligations remain relatively light compared to the developed world — e.g., even after the passage of the National Food Security Bill in September that will subsidize rice, wheat and other grains for much of India’s population, India will spend just $25 billion on food security compared to the $80 billion that the United States spends on food assistance for the poor.

Growth and democracy. ‘India is a messy democracy, things don’t happen in a straight line.’ That’s an understatement, to say the least. But it’s also a gross simplification that India’s messy democracy explains its underperforming economy. Rajan argued that democracy puts a ‘floor’ on poor economic conditions by forcing greater cooperation among political actors as the economy worsens and that ultimately, India’s path to growth through democratically enacted reforms could mark a more enduring and sustainable way to grow. (It’s equally plausible that China’s one-party system is even more responsive to economic pain, however, because China’s Communist Party owns 100% of the responsibility for the economy. Though there aren’t democratic elections to check the government’s power, Xi Jinping has a huge incentive to get economic policy right, lest social unrest sweep aside decades-long Party rule.)

Rajan didn’t say a word about the upcoming election in spring 2014 — and the likelihood that Gujarati chief minister Narendra Modi could come to power within the next seven months. Modi’s a controversial figure in India, but if he’s elected, it will likely be based on his economic stewardship of Gujarat, and Modi may find in Rajan a willing proponent of greater liberalization and reform. Rajan is closer to reformers within the current government than to India’s Hindu nationalist right, and even this week, Modi and Rajan were at odds over a report released by a Rajan-headed committee that labeled Gujarat as among India’s ‘less developed’ states. But Rajan also signaled his political independence when he raised the RBI’s benchmark repurchase rate by 0.25% in late September, a move that put more pressure on the governing United Progressive Alliance (UPA) coalition that Singh heads.

Economic reporting. Rajan intriguingly argued that Indian GDP is underestimated by around 15% because of measurement errors in capturing, in particular, the level of growth in rural industry. Though the world has become rightfully wary of the accuracy of Chinese GDP reporting in recent years, it’s not just a Chinese problem, and GDP measurement is an issue more people should think about (e.g., how much of Italy’s black-market economy does Eurostat miss?).

India-Pakistan FTA. Pakistan’s prime minister Nawaz Sharif remains more enthusiastic about improving the bilateral relationship than Singh. But the two prime ministers found time to meet in New York two weeks ago at the United Nations General Assembly. Though Singh is a lame-duck leader, there’s some hope that India and Pakistan can make progress on bilateral trade, even if the decades-long regional dispute over Jammu and Kashmir and Indian anger over Pakistani-based terror attacks remain more intractable. Interregional trade is artificially stalled, but a free trade regime between India and Pakistan would open new avenues of competitiveness, lower consumer prices, and a wider markets for goods and services in both countries. Closer commercial ties could also help ameliorate longstanding political tensions between the two countries.

Rajan was appropriately politic when I asked him whether he saw India-Pakistan free trade among the priorities for raising GDP growth in India, which is to be expected given the extremely delicate political, military and security issues involved. But he noted that regional economic officials continue to work together, and he affirmed that greater economic integration could simultaneously accompany political engagement. India’s central bank governor isn’t directly responsible for trade policy, of course, but while Rajan is endorsing regulatory reforms and greater infrastructure as low hanging fruit, free trade with Pakistan might be the lowest hanging fruit within reach.