Well, that was quite a blowout. Just a little more than three years after winning power for the first time in Japan, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō) was reduced to just 57 seats in a stunning rebuke in Sunday’s Japanese parliamentary elections.

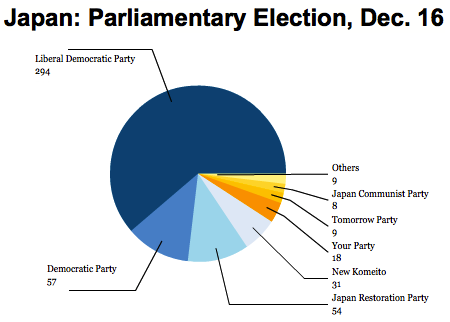

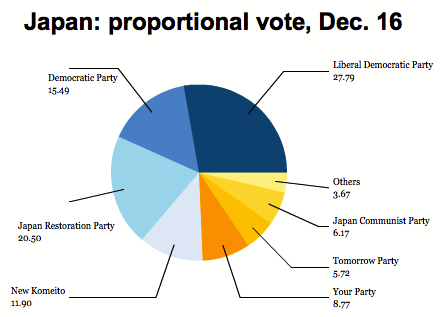

Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三), former prime minister from 2006 to 2007, will return as prime minister of Japan, and the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō), which controlled the House of Representatives, the lower house of Japan’s parliament, the Diet, for 54 years until the DPJ’s win in 2009, has seen its best election result since the early 1990s, with 294 seats. Among the 300 seats determined in direct local constituency votes, the LDP won fully 237 to just 27 for the DPJ. An additional 180 seats were determined by a proportional representation block-voting system, and the LDP won that vote as well:

In contrast, the DPJ has fallen from 230 seats to 57 seats — by the far the worst result since it was created nearly two decades ago. Its previous worst result was after the 2005 elections, when the popular reformist LDP prime minister Junichiro Koizumi (小泉 純一郎) won an overwhelming victory in his quest for a mandate to reorganize and privatize the bloated Japanese post office (a large public-sector behemoth that served as Japan’s largest employer and largest savings bank).

Outgoing prime minister Yoshihiko Noda (野田 佳彦) has already resigned as the DPJ leader, and a new leader is expected to be selected before the new government appears set to take office on December 26.

The result leaves Abe with the largest LDP majority in over two decades — together with its ally, the Buddhist, conservative New Kōmeitō (公明党, Shin Kōmeitō), led by Natsuo Yamaguchi (山口 那津男), which increased its number of seats by 10 to 31, Abe will command over two-thirds of the House of Representatives, thereby allowing him to push through legislation, notwithstanding the veto of the Diet’s upper chamber, the House of Councillors.

It’s a sea change for Japan’s government, and we’ll all be watching the consequences of Sunday’s election for weeks, months and probably years to come. Just a full working day after the election, events in Japan’s politics are moving at breakneck speed.

For now, however, here are 12 of the top takeaway points from Sunday’s election: Continue reading Twelve considerations upon the DPJ wipeout in Japan’s legislative elections