As it turns out, a center-right figure known for his tough talk on ‘law and order’ and immigration who has served for years as prime minister to the most deeply unpopular president in modern French history was probably never the best bet to lead the French left into the 2017 presidential election.![]()

Furthermore, with few signs that they are likely to prevail in the presidential and parliamentary elections later this year, party members in France’s (barely) governing center-left Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) seem to want to use this month’s presidential primary as an opportunity to draw a line for the party’s future — not to choose the most credible future president.

That explains how Benoît Hamon, a 49-year-old leftist firebrand, came from third place to edge both former prime minister Manuel Valls and former industry minister Arnaud Montebourg in the first round of the Socialist presidential primaries on January 22. Party voters this weekend will choose between Hamon and the 54-year-old Valls in a final runoff to decide the official Socialist standard-bearer in the spring’s presidential election.

During the primary campaign, Hamon, an avowed fan of US senator Bernie Sanders, openly called for a universal basic income of €750, making him one of the first major European politicians to do so. At a time when many French reformists argue that the country must abandon the 35-hour workweek it adopted in the year 2000, Hamon wants to lower it to 32 hours (and for his efforts, has won the support of the author of the 35-hour week, Martin Aubry). Hamon would scrap the current French constitution and inaugurate a ‘sixth republic’ that would transfer power away from the president and to the parliament, the Assemblée nationale. To pay for all of this, moreover, Hamon would introduce higher wealth taxes and a novel tax on robotics that approximates an ‘income’ attributable to the work done by such robots.

His slogan?

Faire battre le coeur de la France. Make France’s heart beat.

Though Hamon has often been reluctant to discuss the role of France’s growing Muslim population, he has nevertheless pushed back stridently against Valls for stigmatizing French Muslims (including the ill-fated ‘burkini’ ban introduced after the Nice attacks). Valls, for example, was one of the few members of his party to support the burqa ban in 2010, and as prime minister he attempted (and failed) to strip dual-national terrorists of French citizenship.

While Hamon’s ideas are creative and imaginative, representing the cutting edge among left-leaning economists, for now they seem unlikely to win a majority of the French electorate. Nevertheless, Hamon’s victory signals that the Socialists — much like the British Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn — will be veering far to the left in the future. Depending on the circumstances, Hamon’s rise could soon formalize an increasingly severe rupture between France’s hard left and France’s center-left.

No matter who wins the Socialist primary runoff on January 29, however, the Socialist candidate will be competing against two other figures of the broad left. The first is Emmanuel Macron, a charismatic figure who served as economy and industry minister from 2014 to 2016, when he left the government to form an independent progressive and reform movement, En marche (Forward). In bypassing the Socialist primaries altogether, it’s Macron who may have ‘won’ the most last weekend. The second is Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the candidate of France’s communist coalition, the Front de gauche (Left Front).

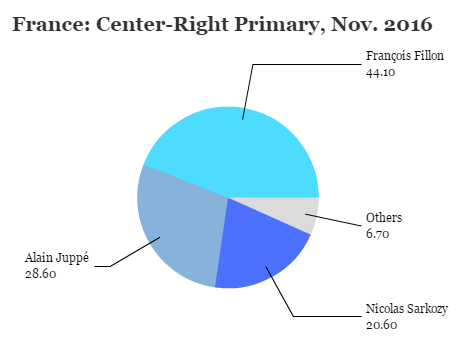

Polls consistently show that Macron is in third place and rising, floating just behind the center-right candidate of Les Républicains, former prime minister François Fillon and the far-right, anti-immigrant candidate of the Front national, Marine Le Pen. Both Hamon and Valls languish in fifth place in those same polls, often in single digits, behind Mélenchon. Leading figures in within the Socialist Party (including 2007 presidential candidate and environmental and energy minister Ségolène Royal) have already all but announced their support for Macron.

If Valls wins the runoff, he risks losing votes in April from the Socialists’ leftists supporters to Mélenchon.

If Hamon wins the runoff, he risks losing votes in April from the Socialists’ centrists supporters to Macron and, indeed, it’s even possible that Macron’s supporters voted in the primary for Hamon to engineer this precise outcome.

Still other long-time Socialist voters, frustrated by income stagnation and joblessness, like what they hear in Le Pen’s economic nationalism and antipathy to both the European Union and immigrants from further afield.

How did it come to this?

Blame François Hollande. Continue reading Benoît Hamon’s rise as Socialist standard-bearer could forever break French left