It’s been perhaps the most sensational rise and fall of a top Chinese official in a generation, but the corruption trial against former Chongqing party leader Bo Xilai (薄熙来) wrapped up this week with plenty of surprises, ![]() even if his guilty verdict for bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power, is all but assured.

even if his guilty verdict for bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power, is all but assured.

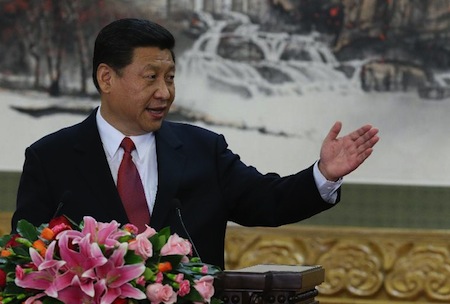

On the final day of what has been a sensation hearing by Chinese standards, Bo accused a top aide of becoming romantically involved with his wife, capping five days of what has been a spirited defense by one of China’s most charismatic 21st century party leaders. Far from showing remorse, Bo (pictured above) has vigorously denied the charges and defended his actions:

He said he never cared for money. “The long johns that I’m wearing now were bought by my mother in the 1960s,” Bo said, suggesting he did not approve of the lifestyle Gu had created for their son, Bo Guagua. “I have been working like a machine. I really don’t have time to care about air tickets, hotel expenses and travel expenses,” Bo said. He added: “The country did not pick me because I am a good accountant.”

That Bo has been allowed to mount such a public (and political) defense is not surprising, given his status as one of the second-generation ‘princelings’ of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党). Even if Bo goes to prison for a decade or longer, the trial will have helped to cement his image as the leader of a ‘New Left’ movement within Chinese politics and society.

But what does that mean for the ‘Chongqing model’ that Bo championed as party secretary in Chongqing from 2007 to 2012?

The ‘Chongqing model’ is a vaguely neo-Maoist approach to governing China that involves a redoubling of state power and control, strengthening state-owned enterprises and aggressively attacking organized crime, while bringing back some truly unique vestiges of the era of former Chinese leader Mao Zedong (毛泽东), such as encouraging the singing of revolutionary-era songs. It’s often contrasted against the ‘Guangdong model’ — a leadership style that encourages private development to blossom instead of through state-sponsored economic policy and at least a passing respect for the rule of law and other institutional reforms.

You can place the two models on the familiar left-right ideological axis — the Chongqing model prioritizes equitable distribution among all classes, the Guangdong model prioritizes the highest economic growth possible. In reality, however, the line between the two models is blurrier. Though the ‘Guangdong model’ is associated with the relatively liberal former Guangdong party chair Wang Yang (汪洋), now a vice premier (though not a full member of the Politburo Standing Committee) in Xi’s government, it was Wang who served for two years as Chongqing party chair as Bo’s direct predecessor. Realistically, the differences among China’s political elite remain smaller than their shared values. Just as there’s little chance that China will return to the days of Mao-era socialist state planning, there’s also little evidence that economic liberalization and reform has led (or will lead in the future) to greater political freedom.

Over the weekend, The Wall Street Journal reported that Xi Jinping (习近平), who took power as Chinese president earlier this year after assuming leadership last November as the general secretary of the party’s Politburo Standing Committee, is also lurching to the left in the first year of what is expected to be his ten-year stewardship of the People’s Republic of China: Continue reading With the end of Bo Xilai’s trial, is Xi Jinping co-opting the ‘Chongqing model’?