The only certainty about the communiqué that resulted from the third plenum meeting of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) is that you should trust no one who claims to have sometime certain to say about its meaning. ![]()

But that hasn’t stopped a phalanx of Sinologists from Beijing to London and from Shanghai to New York from trying to divine the meaning of the communiqué and what it might behold for the next decade of Chinese economy planning under its new president and ‘paramount leader’ Xi Jinping (习近平), who’s also the general secretary of the CCP’s central committee.

So far, Xi has spent much of 2013 waging an anti-corruption campaign at all levels of the CCP and Chinese government, and emphasizing a less ostentatious style of governance (‘four dishes and a soup‘). The most optimistic forecasters, both within and outside China, predicted that Xi and the party’s central committee, a group of the top 350 CCP officials, would move forward during the third plenum with a bold policy agenda that could give some policy substance to Xi’s ‘Chinese Dream’ rhetoric. China’s state-controlled media even encouraged this line of thinking.

Perhaps Xi would finally end China’s one-child policy!

Perhaps Xi would announce the transition to an even more robust private sector!

Perhaps Xi would announce that the value of the renminbi would be determined by the market!

Perhaps Xi would stand on his head, pardon former Chongqing part boss Bo Xilai, sing a couple of ‘Cultural Revolution’ songs from the Mao era, lift the ‘Great Firewall,’ and establish a timetable for Tibetan independence!

No such luck — at least, so far as anyone can tell, though a more precise resolution will emerge in the days ahead. While it’s hard to find two analysts who agree on exactly what the communiqué foretells, . Xi is consolidating his power! Xi’s been stymied by the technocrats! It’s a triumph for the state sector! It’s a triumph for the private sector!

Here’s a brief portion of the 3,500 word communiqué (5,000 Chinese characters):

The Plenum stressed that the successful practice of reform and opening up has provided important experiences for completely deepening reform, and must be persisted in for a long time. The most important matters are persisting in the leadership of the Party, implementing the Party’s basic line, not marching the old road of closedness and fossilization, not marching the evil road of changing banners and allegiances, persisting in marching the path of Socialism with Chinese characteristics, guaranteeing the correct direction of reform and opening up throughout; persisting in liberating thoughts, seeking truth from facts, progressing with the times, seeking truth and being pragmatic, starting from reality in everything, summarizing domestic successful methods, learning from beneficial foreign experience, and daring to move theoretical and practical innovation forward; persisting in putting people first, respecting the dominant role of the people, giving rein to the pioneering spirit of the masses, closely relying on the people to promote reform, stimulating people’s comprehensive development; persisting in correctly handling the relationship between reform, development and stability, we must be bold, our pace must be steady, we must strengthen the integration of top-level design and crossing the river by feeling the stones, both stimulate overall progress and focus breakthroughs, raise the scientific nature of policymaking, broadly concentrate consensus and form joint forces for reform.

Those words might well also serve as a guide to understanding the communiqué itself — ‘crossing the river by feeling the stones,’ indeed. I’m not sure that Sir Humphrey Appleby could have improved on the document’s maddening vagueness. The Wall Street Journal summarized the statement as follows:

The communiqué called for fewer investment restrictions, greater rights for farmers and a more transparent system for local and national government taxing and spending—all areas where economists say China badly needs reform. But in lieu of specific plans it ambiguously emphasized the need to “encourage, support and guide” the private sector, while at the same time reaffirming “the leading role of the state-owned economy.”

In a small acknowledgment of the clamor for better protection of individual rights, the communiqué noted the need to establish an independent judiciary. But again it reaffirmed the leading role of the party, which has the power to trump China’s constitution.

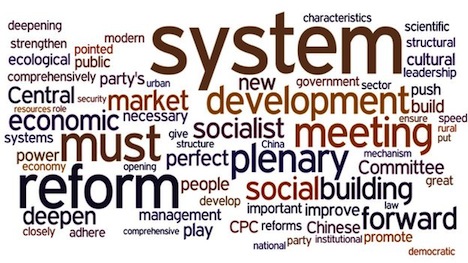

Here’s an even more useful WSJ post that provides eight different takes from economists on the communiqué’s meaning. Perhaps the most helpful analysis comes from the BBC, which published the following word cloud of the communiqué and otherwise argued that the statement represents a stay-the-course commitment to economic reform:

But vague has long been in vogue on the path of Chinese policymaking, especially economic policy. Is it any less vague for China specialists to make vague calls for Xi to ‘deliver’? What would that entail? Looking back, even today, can you list with certainty the five top policy legacies will be for Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) and the Chinese leadership between 2002 and 2012?

Over the course of this week, we’ve watched US president Barack Obama apologize for the rollout and planning of one particular reform to one sector of the US economy. Yes, health care is a relatively large sector of the economy and yes, the government is already an important player in that sector, in light of Medicaid programs for the poor, Medicare programs for the elderly, Social Security benefits for the disabled and a separate care system for veterans and those in the armed forces. But it’s not clear if the Obama administration has any idea what will happen to the private health care insurance market over the next two months, let alone the next ten years.

Now imagine the task at hand for Xi Jinping and the Chinese government, who are expected to set a course not just for China’s health care sector, but for the entire economy, including a sizable public sector and a private sector that’s still very much linked to state power — in a country with 1.35 billion people, which is a population of about, oh, one billion more than in the United States. It’s a country that has about 42 cities with a population equivalent to or greater than the size of Chicago. Continue reading What we know (and what we don’t) about China’s CCP ‘third plenum’ meeting