It’s only Tuesday, but it has not been the best week for former US secretary of state Hillary Clinton. ![]()

![]()

Just a day after reports that the FBI discovered nearly 14,900 emails that Clinton should have turned over as work-related emails to the State Department (she turned over 30,000 and marked the rest as private), the Associated Press reported on Tuesday afternoon that, in an analysis of 154 private individuals that Clinton met while secretary of state, 85 of them were at least one-time donors to the Clinton Foundation, an international health charity organization — if true, that means that around 55% of her meetings with non-government and non-foreign officials were with Clinton Foundation donors.

First, it’s unlikely that Clinton, in four years at State, met just 38 people on average annually from the private sector, so there’s so doubt about whether the AP’s denominator is accurate. Secondly, without any other proof, a meeting is not anything more than just a meeting, especially after a thoroughgoing investigation from the US Federal Bureau of Investigation almost certainly reviewed the question of quid pro quo corruption. Third, it’s credible that many private-sector actors (especially wealthy individuals with storied careers in academia, finance, technology or otherwise) might have given money to a high-profile charity like the Clinton Foundation. Finally, and most importantly, while Clinton is not exactly a paragon of government ethics, it beggars belief that she would sabotage her own obvious 2016 presidential hopes by engaging in crude pay-to-play corruption.

It’s true that both Hillary Clinton and her husband have both shown ridiculously poor ethical judgment when entrusted with power, and it was only in July that FBI director James Comey (narrowly) declined to recommend criminal charges for Clinton’s handling of classified information on a home server that she used for email while at State. Both Clintons, already wealthy from book royalties, have also shown reckless greed in taking millions of dollars in speech fees from corporate and foreign interests since leaving office.

But short of one truly horrific example, and a particularly immature staffer in Doug Band, there’s not a lot of scandal involving the Clinton Foundation. (The example, reported last year to surprisingly little fanfare, involves a murky Canadian financier named Frank Giustra, a leading figure in a sale of a uranium company, Uranium One, that won approvals from State and numerous other US agencies. The deal, ultimately, handed over rights of one-fifth of US uranium reserves first to Kazakh and then to Russian control).

By and large, the Clinton Foundation a charity that leverages the Clinton family’s name and experience toward better global health outcomes. In that sense, it’s no different, really, than the Carter Center or any other private-public effort that a former US president undertakes.

In politics, though, especially in the crucible of US election-year politics less than 80 days from a presidential election, reality is less important than perception. And Clinton most certainly has a perception problem with the Clinton Foundation and the idea that it’s become a pay-for-play racket. Moreover, the Clinton Foundation gets generally great marks from charity scorecard watchdogs like Charity Watch. Despite the phony statistics of right-wing news media, the Clinton Foundation spends an admirably 88% of donations on programming.

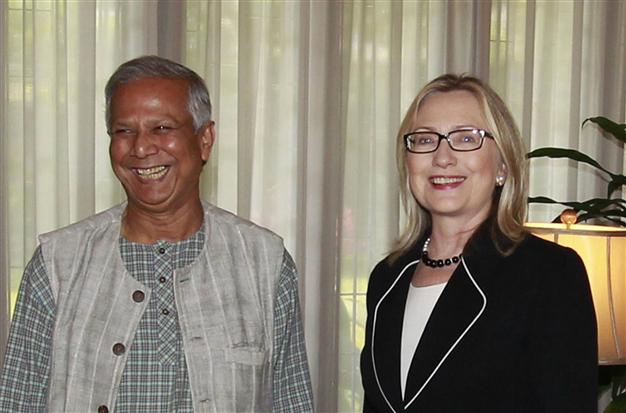

But the most especially ridiculous aspect of the latest uproar over the Clinton Foundation is that one of those 85 individuals that Clinton met is Muhammad Yunus, the former head of Grameen Bank. Frankly, it would have been diplomatic malpractice not for Clinton to have met Yunus during her time at State, when Yunus was increasingly under attack from his own government.

By 2011, Bangladesh’s increasingly autocratic and corrupt leader, Sheikh Hasina, had expelled Yunus and fully expropriated Grameen Bank. Though the Bangladeshi government once tried to accuse Yunus himself of embezzlement, it eventually ousted him from Grameen on the basis that, then at age 72, he exceeded the retirement age. Continue reading Muhummad Yunus is exactly the person Clinton should have been meeting