He won the Costa Rican presidency yesterday with 78% of the vote. His opponent considered the runoff so hopeless that he conceded defeat and suspended his campaign a month ago. With nearly 1.3 million votes, he won more votes than any other Costa Rican presidential candidate in the country’s modern history.![]()

But now that he’s been officially elected Costa Rica’s new president, what will Luis Guillermo Solís (pictured above) do in office?

The first thing he’ll have to do is temper high expectations that Costa Rica’s first third-party president in modern history will suddenly transform the country into a wealthier, corruption-free, social democratic paradise.

The son of a cobbler and the grandson of a laborer on a banana plantation, Solís vowed to reverse the income and social inequality that’s become a growing concern in what is arguably Central America’s most politically and economically successful country.

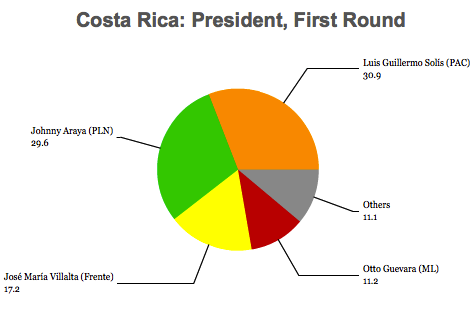

Solís, a historian who has never held elective office, won a surprise victory won the first round of the presidential election on February 2, edging out one-time frontrunner Johnny Araya, the candidate of the ruling Partido Liberación Nacional (PLN, National Liberation Party) and the longtime mayor of San José. Solís’s strong showing against Araya in the final presidential debate bolstered his candidacy, which had languished in fourth or fifth place in polls, even a week before the February vote.

It was a magnificent turnaround for a candidate who barely figured in the polls at the end of 2013.

Solís won 77.85% in Sunday’s runoff, while 22.15% voted for Araya, despite the suspension of Araya’s campaign on March 6. He said that he’ll start announcing key members of his cabinet next Monday, April 14.

Araya was attempting to win a third consecutive presidential term for the PLN. In the 2010 vote, Costa Ricans elected Laura Chinchilla as the country’s first female president. Despite initially high expectations, Chinchilla’s administration has been a disaster, marred by embarrassing corruption scandals within the PLN and charges of lackluster economic policy.

Costa Rican voters also had doubts about Araya’s leading challenger, the far more leftist José María Villalta, the candidate of the socialist Frente Amplio (Broad Front), who had been expected to advance to a runoff against Araya.

So it’s not a surprise that voters would turn to Solís, who offered a slightly more leftist vision for Costa Rica than Araya and the PLN, but not so socialist as Villalta and the Broad Front.

He’ll take office with an incredibly fragmented Asamblea Legislativa (Legislative Assembly) — his own party, the Partido Acción Ciudadana (PAC, Citizen’s Action Party), holds just 13 seats in the 57-member chamber. That means he’ll have to form an alliance with the PLN, which holds 18 seats, or form ad-hoc coalitions with other lawmakers who range in ideology from Christian democratic to radical libertarian to chavista-style socialist.

It helps that Solís — and the PAC’s unofficial leader Ottón Solís (no relation to the president-elect) both started their political careers with the PLN. Ottón Solís, elected in February to the National Assembly as a deputy, will play an important role in forming and achieving the new administration’s agenda. For the past decade, opposition to the ruling PLN and to corruption has united the PAC, and it’s ideological diversity has been helpful in the 2014 campaign. Once in government, however, Luis Guillermo Solís may find it difficult to unite a party that contains both socialists and liberals — and to maintain a constructive role for Ottón Solís. Continue reading What will Solís do as Costa Rica’s new president?