Over the past month, Nicaragua has been working to push forward with a plan to build a canal linking the Pacific Ocean to the Caribbean Sea — a dream that predated the actual construction of the Panamá Canal in 1914.

The original push in the United States for a canal through Central America started as the dream of U.S. senator John Tyler Morgan of Alabama, a former Confederate colonel during the U.S. civil war, who hoped that a canal through Nicaragua would restore the U.S. south to economic prominence, and he pushed throughout the 1880s for a Nicaraguan canal, in particular, long before Panamá, then itself the northernmost province of the Republic of Colombia, was a serious option, despite the fact that the engineer of the Suez Canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps, had failed in French-led efforts to build a canal through the isthmus of Panamá.

19th century Nicaraguan dreams turn to 20th century Panamanian realities

After the French disaster in Panamá — beset by corruption, disease and ultimately failure — Nicaragua seemed the clear favorite for U.S. interests in the construction of a Central American canal. The story of how Wilson Nelson Cromwell (who helped found the law firm Sullivan & Cromwell) and Philippe Bunau-Varilla transformed public opinion, first within the administration of former U.S. president William McKinley and, thereafter, Theodore Roosevelt, and then in the U.S. Congress, to favor a Panamanian route as speedier and less costly is one of the most amazing stories in the history of congressional lobbying. After all, Panamá already featured a French railway to facilitate construction, ports on either side of the isthmus, the remnants of the aborted French canal effort, and it would, after all, be much shorter than any Nicaraguan canal.

As debate in Congress ultimately turned into a battle of the routes, Bunau-Varilla and U.S. senator Mark Hanna, a top Republican powerbroker, had worked to convince skeptical colleagues that Nicaragua’s volcanic activity made it too unstable for a canal. Incredulously, Hanna delivered a speech on the Senate floor purporting to show all of Nicaragua’s supposed active volcanoes would make the route more difficult.

But the tour de force turned out to be a stamp — as Matthew Parker writes in Panama Fever: The Epic Story of One of the Greatest Human Achievements of All Time:

Over the next few days Bunau-Varilla scoured the philatelists of the capital looking for a certain 1900 one-centavo Nicaraguan stamp, which he had come across the year before. In the foreground of the stamp is pictured a busy wharf while in the background rises the magnificent bulk of Mount Momotombo. In an artistic flourish the illustrator had added smoke to the top of the volcano, which was actually more than a hundred miles from the proposed Nicaragua canal. Just before the vote, every senator was sent this ‘evidence’ of the dangers of the Nicaragua route.

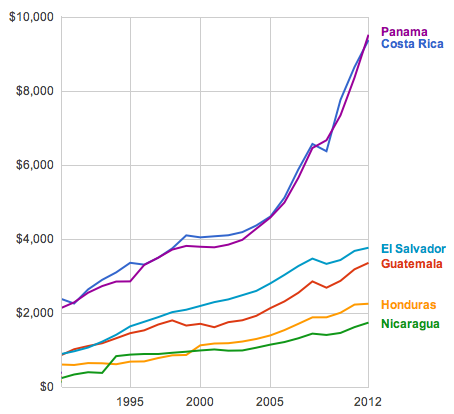

Ultimately, the vote favored Panamá over Nicaragua by just eight votes. Roosevelt’s administration thereafter embarked on the self-interested cause of Panamanian independence from Colombia and, having helped deliver such independence in 1903, commenced building the Canal over the next decade, with U.S. doctors and engineers learning how to reduce yellow fever and malaria along the way through the reduction of mosquito populations. Though the United States controlled the Canal through much of the 20th century, U.S. president Jimmy Carter formally agreed in a 1977 treaty to cede control of the Panamá Canal Zone back to Panamá. Since that transition in 1999, Panamá has reaped much of the economic benefit of the Canal’s income, which has helped Panamá become one of Central America’s strongest economies, and the country is preparing for the completion of a project in 2014 to widen the Canal, thereby expanding Panamanian economic opportunities.

A Sandinista canal

Fast-forward nearly a century, and Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega hopes to succeed where over a century’s worth of futile dreams have failed — that is, with a little help from the Chinese.

Ortega came to power for the first time in 1979 when his Sandinista revolutionaries overthrew U.S.-backed dictator Anastasio Somoza, the last of a line of three Somoza family members that had controlled Nicaragua since the mid-1930s. Somoza was no great loss for Nicaragua, but his overthrow came at a difficult time for the country, which was slowly recovering from an earthquake in 1975 that had essentially leveled Managua, the capital, hastening its long-term decline as the financial capital of Central America to the rising Panamá City. Ortega came to power as part of a Sandinista junta, and though he slowly emerged as Nicaragua’s top leader as president from 1985 to 1990, his rise to power led to one of the most brutal proxy fights of the Cold War, with Ortega and the Sandinistas turning to the Soviet Union for support and the United States clandestinely arming and supporting the ‘Contras,’ plunging the tiny Central American country into a decade-long civil war.

Ortega (pictured above) stepped down in 1990 after losing the presidential election, but as Nicaragua slowly recovered from the carnage of the 1980s, and as Nicaraguans suffered through a long line of democratically elected, if massively corrupt and mediocre presidents, Ortega retained a strong following, especially among the country’s poorest residents. He returned to power in 2006 after winning a highly fragmented election under the old Sandinista banner (FSLN, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional), having remade himself as a democratic socialist along the lines of Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. Ortega, who quickly consolidated the instruments of power, eliminated the hurdle of term limits and was overwhelmingly reelected in November 2011 under conditions that were tilted widely in favor of the Sandinistas.

But unlike in the 1980s, when Ortega seemed to be genuinely interested in eliminating corruption and establishing a new more just, socialist era for Nicaragua, Sandinista 2.0 has jettisoned the ideology for a state capitalist model that’s just as corrupt as the Somoza era ever was. Continue reading Don’t take the concept of the Nicaraguan Canal seriously until the Chinese government does →

![]()

![]()