With now less than 40 days to go until Germany’s federal elections, polls show that chancellor Angela Merkel is by far the most popular candidate to return as chancellor and her party, the Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union), will clearly be the largest bloc in Germany’s Bundestag after the election.

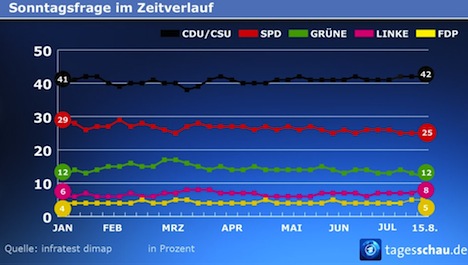

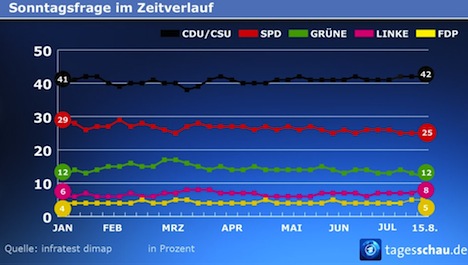

Polls have been remarkably consistent throughout much of the year leading up to the September 22 vote. The center-right CDU, together with its Bavarian sister party, the Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern (CSU, the Christian Social Union), overwhelmingly leads Germany’s largest center-left party, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, the Social Democratic Party), and voters overwhelmingly prefer Merkel to the SPD’s candidate for chancellor, Peer Steinbrück — by a nearly two-to-one margin. Here’s the trendline from Infratest dimap, which released its latest poll this week:

This week’s news that Germany leads GDP growth in the eurozone, which itself pulled out of recession in the second quarter of 2013, will only buoy Merkel’s chances. Barring a huge shift in public opinion that has only calcified over the past year, Steinbrück, a bland technocrat who comes from the right wing of the SPD and who served as finance minister in the ‘grand coalition’ government of 2005 to 2009, will lead the SPD to a loss of nearly historic proportions. But while that means Merkel is very likely to return as chancellor, the composition of Merkel’s third government is less certain.

That’s because support for Merkel’s current coalition partners, the free-market liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), has collapsed since the previous September 2009 election, when it won 14.6% of the vote and 93 seats in the Bundestag, a record-high electoral performance for the party. But since 2009, the FDP has struggled to maintain a presence in local Germany elections, losing support in state after state. Its decade-long leader Guido Westerwelle, the first openly gay party leader in German history, stepped down in April 2011 as party leader and vice chancellor (though he remains foreign minister) after the FDP won barely 5% in the state elections of Baden-Württemberg. His successor as FDP leader is the Vietnamese-born Phillip Rösler (pictured above), who began his career in Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen) and who had served previously as health minister in the CDU/FDP coalition government from 2009 to 2011.

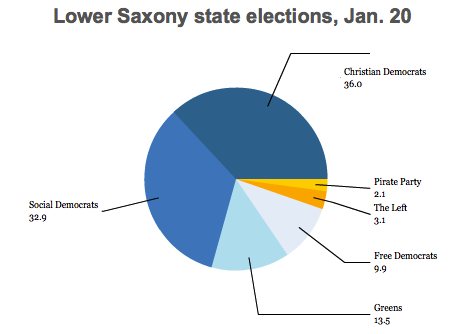

Although Rösler has not lifted the FDP back up to its 2009-level heights, he has managed to staunch the party’s decline. In the May 2012 elections in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany’s most populous state, the FDP managed to win 8.6% of the vote, an increase of nearly 2% from the previous election, though that’s largely due to the popularity of Christian Lindner, who led the FDP’s 2012 campaign. More recently, though, in Lower Saxony’s state election in January 2013, the FDP won 9.9% of the vote, a gain of 1.7%.

It’s also because Germany’s electoral system is notoriously complex. Germans will actually cast two votes in September — the first is for a candidate to represent one of 299 electoral districts in Germany, the second is for a German political party. The second ‘party vote’ is meant to determine the party’s ultimate total share of seats in the Bundestag, and so a party will receive additional seats on the basis of the party vote sufficient to provide that its percentage of seats in the Bundestag is roughly equal to the percentage of votes it received pursuant to the party vote (so long as the party receives at least 5% of party vote support). That means that the number of seats in the Bundestag changes from election to election — although it must have a minimum of 598 seats, it has had as few as 603 and as many as 672 since German reunification.

The FDP has struggled all year long to achieve merely 5% support in opinion polls and, while it’s doing better in polls than it was at the beginning of the year, there’s no guarantee that it will meet that threshold:

That means that, more than anything else, the composition of Germany’s next government turns on the FDP’s performance. If it wins less than 5%, Merkel will not have the option of continuing a coalition with the FDP. Moreover, even if the FDP wins more than 5%, it may still not win enough seats to cobble together a CDU/FDP majority in the 598-member Bundestag.

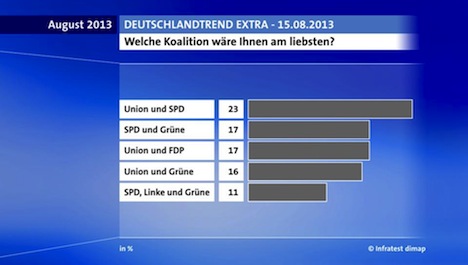

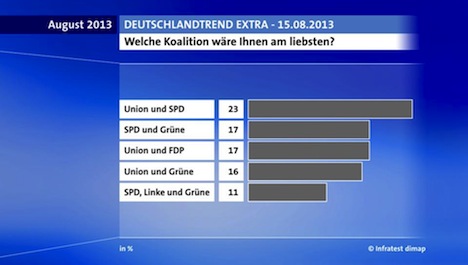

Furthermore, polls show that while German voters overwhelmingly prefer Merkel as chancellor, they actually favor a return to the CDU/SPD grand coalition, more than the current CDU-led government or a potential SPD-led government:

Two additional coalitions — a CDU/Green government and a united left coalition among the SPD, Green and Die Linke (the Left Party) — also win significant support.

But what are the chances that any of these five coalitions will actually emerge after September 22? Here’s a look at each potential coalition and the chances that it could form Germany’s next government.

The current government: CDU/FDP.

The current government: CDU/FDP.

Merkel prefers to continue her current coalition over any alternative because her political agenda matches well with the FDP’s political agenda. Any negotiations between Merkel and the SPD or the Greens would entail huge concessions from Merkel that she would not otherwise have to make in coalition with the FDP. But, as noted above (and as represented in the graph to the right, on the basis of current polls), it’s unclear if that coalition can win a majority.

Under Rösler’s leadership, the FDP is running on a campaign of lower taxes and liberalizing Germany’s economy, which is standard Free Democratic fare, and both the FDP and Merkel’s CDU oppose new tax increases. Their largest policy difference might be same-sex marriage — the FDP supports it and the CDU (and especially the Catholic-influenced CSU) oppose it, although the FDP has taken a much stronger stand on privacy rights than Merkel’s CDU.

Even if they win enough seats to form a majority, no one expects the margin to be larger than the government’s current 21-seat margin. So even a single-digit majority could turn out to be a Pyrrhic victory if Merkel finds herself forced to look outside her own government to enact her legislative agenda on an ad hoc basis, especially with respect to European Union matters, given the sometimes eurosceptic nature of many CSU deputies. That’s hardly a recipe for stable government.

Polls in August show that together, the current government will win between 44% and 47% of the vote if the election were held today. Unfortunately, that doesn’t give us much of an idea about whether they’ll have enough support in the Bundestag to form a majority. Since reunification, Germany has held only six federal elections — they’ve resulted in three CDU-led governments, two SPD-led governments and a single CDU-SPD grand coalition. Continue reading Assessing the potential coalitions that might emerge after Germany’s federal elections →

![]()

![]()