Japan’s long-serving emperor, Akihito, stunned his country Monday in a video address, during he heavily hinted that the Japanese parliament should consider permitting his future abdication.![]()

The emperor did not fully endorse legislation to allow abdication, out of respect for the tradition that emperors do not intervene directly in Japanese politics. But at age 82, Akihito, who has suffered from increasingly poor health in recent years, made it abundantly clear that he believes that his retirement would be a good thing for the Japanese people — if the current government finds a way to amend the imperial succession laws. In addressing the Japanese people directly, and in reinforcing the emperor’s role as a symbol of postwar pacifism, Akihito also contrasted with the post-imperial views of prime minister Shinzō Abe, perhaps the most nationalist of Japan’s postwar civilian leaders.

No matter what happens, Akihito’s address signals that his son, the 56-year-old Naruhito, could take a much more high-profile role in the future. If the Diet enacts legislation permitting abdication, Naruhito might even soon become Japan’s new emperor.

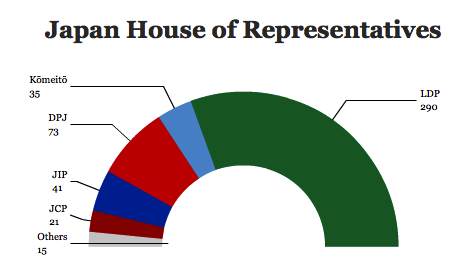

The abdication question is now just one of several issues on Abe’s desk after his dominant Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō) made gains in elections last month in the House of Councillors, the upper house of the National Diet (国会, Kokkai), the Japanese parliament. Among other things, Abe has postponed a long-planned increase in the national consumption tax and has doubled down on what’s already been nearly four years of fiscal and monetary stimulus to improve Japan’s long-stagnant economy. Above all, he still harbors dreams of revising Japan’s pacifist constitution by amending Article 9, the famous provision that outlaws war and technically forbids a standing Japanese army (though, in reality, the so-called Japan Self-Defense Forces have more personnel than the United Kingdom’s army).

Akihito’s Monday afternoon address, however, brings the Japanese imperial tradition to the forefront of Japan’s often muted (by American standards, at least) political agenda. The Chrysanthemum Throne dates back nearly three millennia as the world’s oldest continuing hereditary monarchy. Japan’s emperors, however, traditionally wielded more moral and spiritual power than actual power. That was true in the Tokugawa era, and it’s been true since the end of World War II when the United States and its allies rehabilitated the imperial institution to use Hirohito, who reigned from 1926 to 1989, as a link from pre-war to post-war Japan.

Hirohito, in the immediate postwar period, admitted publicly that the emperor was not, in fact, a god. Akihito’s wife, Michiko, is the first commoner to serve as empress, and they have tried to make the throne more accessible to the Japanese people. Naruhito, in particular, has indicated that he would like to continue to break down some of the formality surrounding the imperial family. Continue reading Naruhito could soon become Japan’s next emperor