The images from Taksim Square over the past week, culminating in conflict between protesters and Turkish police authorities, have stunned a global community that’s used to thinking of Turkey — and, in particular, Istanbul — as a relatively tranquil secular meeting point of East and West.

Although I’ve not written much about Turkey through Suffragio, it’s a fascinating country that I was delighted to visit in 2010, at the height of the glory days of the government of its current (and now embattled) prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Ultimately, there are two questions at issue here: how to evaluate Erdoğan’s performance prior to the recent protests, on the one hand, and how to evaluate Erdoğan’s performance during and in response to the protests, on the other hand.

Although Western commentators have increasingly argued of Erdoğan’s move toward increasing Islamization and authoritarianism, I worry that those calls misunderstand the depth of Erdoğan’s support and the nature of what modern Turkey (it is, after all, a country that’s over 98% Muslim) has become today. But it is impossible to watch Erdoğan’s repression of basic political freedoms, such as his government’s recent moves to disrupt a planned May Day protest, and the ongoing brutal police response to the Taksim Square and increasingly, nationwide, protests without admitting that whatever legitimacy Erdoğan once enjoyed is rapidly dissipating, and Erdoğan, his government, Turkey’s president, Turkey’s military, and Turkey’s awakened — and rightfully angry — protest movement, are all trapped in a suddenly perilous standoff.

It’s all the more fragile given the ongoing civil war in Syria. Not only has the Erdoğan government been unsuccessful in persuading one-time ally Bashar al-Assad to pursue a more moderate course, the growing number of refugees from Syria within Turkey’s borders means that Turkey risks being drawn into a wider regional conflict (though, in one of the few humorous asides to the ongoing protests, Syria has now issued a travel warning for Turkey).

Erdoğan’s initial position was legitimate and democratic

When Steven Cook wrote in The Atlantic earlier this month, that ‘while Turkey is perhaps more democratic than it was 20 years ago, it is less open than it was eight years ago,’ I had two initial reactions. First and foremost, shouldn’t we care more, from a pure governance standard, that Turkey’s government is representative and responsive to its electorate than it hews to some Westernized standard of ‘openness’? What does ‘less open’ even mean? Secondly, when Cook laments Turkey’s ‘less open’ nature, he doesn’t equally lament that the European Union virtually slammed the door in the face of Turkey’s application to join the European Union in 2005, when despite the opening of negotiations for Turkish accession, it became clear any road for Turkey’s EU membership would be long and arduous. It may be difficult to remember today, but it’s a push that Erdoğan’s government made even more passionately than the governments that preceded it.

Turkey, let’s be clear, didn’t leave Europe. Europe left Turkey, which has focused on becoming a more important regional player in the Middle East in recent years.

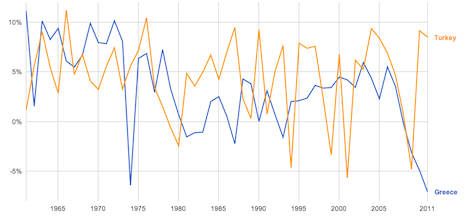

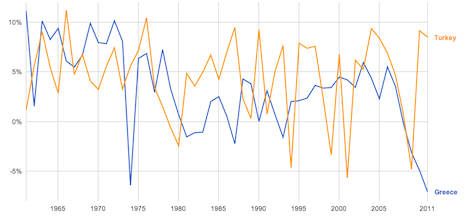

More importantly, from a day-to-day perspective for most Turks, Erdoğan ushered Turkey into a new era of economic reform and modernity, partly due to his enthusiasm to enter the European Union in his first term. But despite the futility of Erdoğan’s initial rationale, Turkey’s economic gains are real, the country certainly remains under much better economic stewardship than Greece or much of Europe:

But Cook, and similar analysts, I fear, are not placing enough weight on the fact that Erdoğan has delivered Turkey’s most responsive and democratically accountable government since the foundation of the modern Republic of Turkey in 1923. And when I read critiques of Erdoğan that cast him as a modern-day ‘sultan,’ I have to cringe because it’s intellectually lazy for opponents to slap Orientalist labels on Erdoğan simply because they disagree with his policy choices.

The Economist on Sunday trumpeted a foreign diplomat who argues that ‘this is not about secularists versus Islamists—it’s about pluralism versus authoritarianism,’ though the question remains — pluralism compared to what? The governments that came before Erdoğan? Some Western fantasy of what Turkey’s government should be?

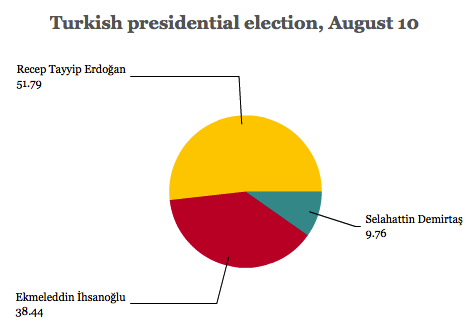

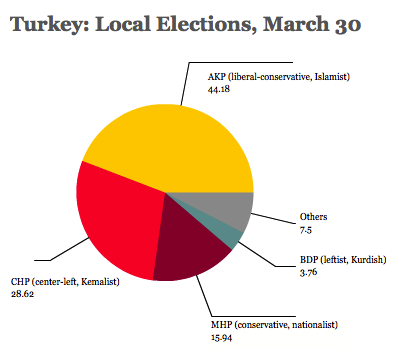

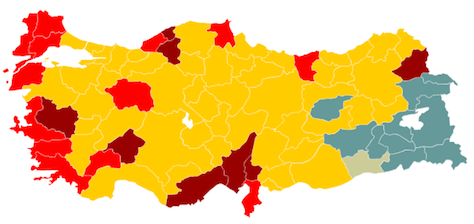

Erdoğan is neither a sultan nor a dictator, but the duly elected leader of Turkey’s government for over a decade, enjoying the repeated success of consecutive democratic victories in election after election.

Continue reading Hand-wringing over Erdoğan is alarmist, but Turkey’s still trapped in a perilous standoff →

![]()